Philip Dray - A Lynching at Port Jervis: Race and Reckoning in the Gilded Age

Here you can read online Philip Dray - A Lynching at Port Jervis: Race and Reckoning in the Gilded Age full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2022, publisher: FarrarStraus, genre: Detective and thriller. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:A Lynching at Port Jervis: Race and Reckoning in the Gilded Age

- Author:

- Publisher:FarrarStraus

- Genre:

- Year:2022

- Rating:4 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

A Lynching at Port Jervis: Race and Reckoning in the Gilded Age: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "A Lynching at Port Jervis: Race and Reckoning in the Gilded Age" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

A Lynching at Port Jervis: Race and Reckoning in the Gilded Age — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "A Lynching at Port Jervis: Race and Reckoning in the Gilded Age" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

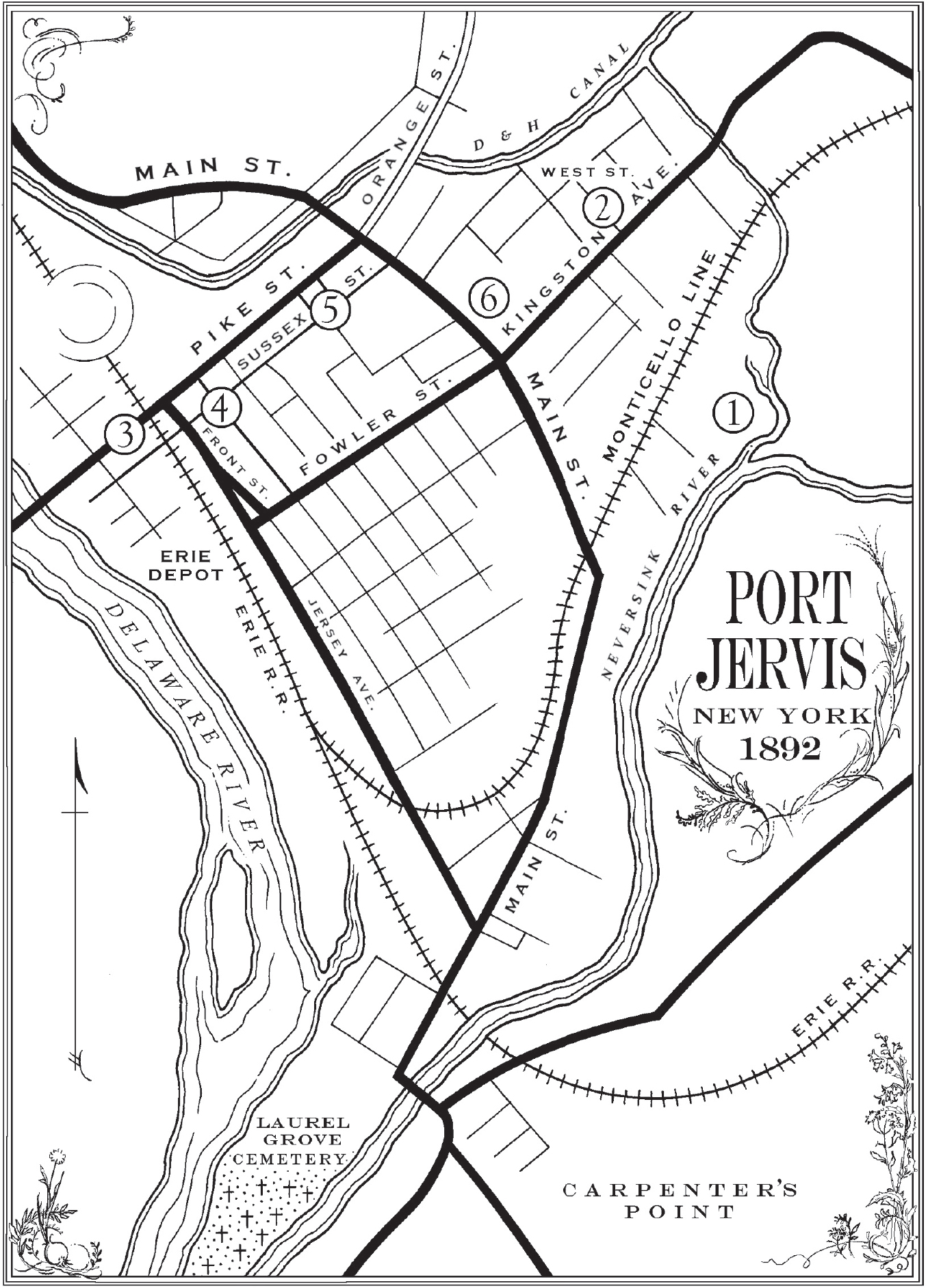

1. Lena McMahon allegedly assaulted 2. McMahon home, 3 West St. 3. Delaware House 4. Village lockup, Ball and Sussex 5. Orange Square 6. Robert Lewis was lynched here.

Nations reel and stagger on their way; they make hideous mistakes; they commit frightful wrongs; they do great and beautiful things. And shall we not best guide humanity by telling the truth about all this, so far as the truth is ascertainable?

W.E.B. DU BOIS, Black Reconstruction in America, 1935

One morning in the spring of 1985, I drove along a country road in Alabama to the Tuskegee Institute, one of Americas oldest and most venerated Black colleges. I was researching a book about the 1964 murder of the civil rights workers James Chaney, Andrew Goodman, and Mickey Schwerner in Mississippi and had heard there was a folder on the case in a collection at Tuskegee, then known as the lynching archives. When a librarian led me to the room where the materials were kept, I was surprised to see not a solitary cabinet, as Id expected, but dozens of containers and cardboard boxes, sixty-three in number. She explained these held a centurys worth of newspaper clippings and other published accounts of the many thousands of lynchings in the United States, most of African Americans.

This substantial repository, overseen by the pioneering Black sociologist Monroe Nathan Work in the years 19121935 and maintained for decades by students and staff, had defied lynchings code of impunity and silence. It had done this by refusing to allow the stories of what the crusading Black journalist Ida B. Wells called Americas national crime to be forgotten and die along with its victims. Notably, I was told this archive held only the known cases, those recorded by the press or civil rights groups, but that an immeasurable number still remained unknown or unsubstantiated.

It was my encounter with the Tuskegee collection and its unavoidable truththat lynching was not a series of random, aberrational incidents but an institutionalized form of white terrorthat led me to write the book At the Hands of Persons Unknown: The Lynching of Black America, which was published in 2002.

The chronological accounts in the Tuskegee collection, although drawn from all over the country, chiefly concerned the Southern states, where historically most lynchings took place. But incidents of racialized mob violence occurred in the North as well. There, given their infrequency, and because they tended to reveal the hypocrisy of the regions vaunted superiority as a place of assured civic authority and respect for the rule of law, they often attracted greater notoriety.

Several years ago, I was drawn to examine one such case. It occurred in Port Jervis, New York, on June 2, 1892, and claimed the life of a young Black man named Robert Lewis. It was infamous at once, for it was seen as a portent that lynching, then surging uncontrollably below the Mason-Dixon Line, was about to extend its tendrils northward. There had been a sharp rise in the reported number of Black people killed in this manner in recent years74 in 1885; 94 in 1889; 113 in 1891. The year 1892 would see the greatest number, 161, almost one every other day. The nations newspapers were rarely without news of a lynching somewhere, a crime that emerging Black activists described as driven by the impulse to thwart African Americans social and economic advance toward equality and full citizenship, by the presumption that Black people were inherently criminal, and by white mens insecurity about Black male sexuality and threats to male hierarchy generally.

What perplexed white Port Jervians and other New Yorkers was why a lynching had occurred in a village just northwest of New York City with a modest African American population of roughly two hundred men, women, and children, or 2 percent of its approximately nine thousand residents. Although the town was hardly free from the common social and economic inequities of the era, and its normalized racism, it had no flagrant history of racist mob violence.

The man put to death by the Port Jervis mob, Robert Lewis, was a twenty-eight-year-old teamster, or bus driver, for the towns leading hotel, the Delaware House, who had allegedly beaten and sexually assaulted Lena McMahon, a young white woman. Lewis, before being killed, was reputed to have confessed to the crime but had also named McMahons white boyfriend as an accomplice.

Sensational news stories of violent crime in the streets of large cities like Boston, Philadelphia, and Chicago might have been consumed by readers and as quickly forgotten. Not so with the troubling bulletin of a lynching at Port Jervis. Because such incidents reported then occurred almost exclusively in the South, the fact that a lynching had taken place in a community only sixty-five miles and a two-hour train ride from Manhattan, and had been witnessed by two thousand people, brought immediate national condemnation. Situated at the confluence of the Delaware and Neversink Rivers, where the states of New York, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania meet, Port Jervis was a largely peaceful, orderly burg, surrounded by water and mountains, attractive to city folk who came in summer to fish for trout, canoe in the scenic Delaware, or enjoy a breeze on the verandas of the local boardinghouses.

(Collection of the Minisink Valley Historical Society)

In recent years, due to the efforts of a small group of current and former residents, and the influence of the Black Lives Matter movement, there has been new interest in the lynching of Robert Lewis at Port Jervis, arguably the most troubling incident in the citys past. But decades of aversion to the subject have left many residents, Black and white, substantially unfamiliar with it. This collective lack of remembering (or remembrance) has been determined and willful, a result of the towns profound shame over the lynching itself, as well as the ensuing humiliation when, after vowing to punish those responsible, the community failed to do so. Lingering resentment at being singled out for censure and the lack of overt efforts by whites to mend relations with fellow Black citizens have been exacerbated by a far more slow-motion calamitythe loss by the middle of the twentieth century of Port Jerviss prominence as a Northeast rail, industrial, and commercial hub.

The yellowing pages in the Tuskegee archive derive their authority from the irony that the very aims of lynchingthe denial of due process, the oblivion of the act itself, and the lasting anonymity of participantswere undone by the reality that such crimes made for scandalous newspaper copy. A white woman violated, a Black man accused, a gallant posse in pursuit, the peoples righteous vengeance attainedsuch elements fed multiple days of headlined coverage wherever lynching occurred, from initial alarm and outcry to the ultimate barbaric spectacle.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «A Lynching at Port Jervis: Race and Reckoning in the Gilded Age»

Look at similar books to A Lynching at Port Jervis: Race and Reckoning in the Gilded Age. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book A Lynching at Port Jervis: Race and Reckoning in the Gilded Age and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.