THE PHNIX

IN former times, when hardly anybody thought of travelling for pleasure, and there were no Zoological Gardens to teach us what foreign animals and birds were really like, men used to tell each other stories about all sorts of strange creatures that lived in distant lands. Sometimes these tales were brought by the travellers themselves, who loved to excite the wonder of their friends at home, and knew there was nobody to contradict them. Sometimes they may have been invented by people to amuse their children; but, anyway, the old books are full of descriptions of birds and beasts very interesting to read about.

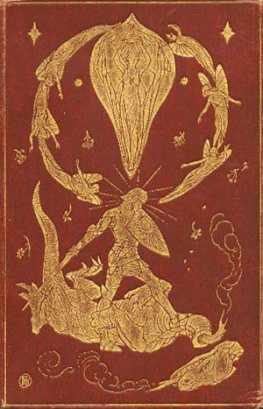

One of the most famous of these was the Phoenix, a bird whose plumage was, according to one writer, 'partly red and partly golden,' while its size was 'almost exactly that of the eagle.' Once in five hundred years it 'comes out of Arabia,' says one old writer, 'all the way to Egypt, bringing the parent bird, plastered over with myrrh, to the Temple of the Sun (in the city of Heliopolis), and then buries the body. In order to bring the body, they say, it first forms a ball of myrrh as big as it can carry, puts the parent inside, and covers the opening with fresh myrrh; the ball is then exactly the same weight as at first; thus it brings the body to Egypt, plastered over as I have said, and deposits it in the Temple of the Sun.' This is all that the writer we have been quoting seems to know about the Phoenix; but we are told by someone else that its song was 'more beautiful than that of any other bird,' and that it was 'a very king of the feathered tribes, who followed it in fear, while it flew swiftly along, rejoicing as a bull in its strength.' Flashing its brilliant plumage in the sun, it went its way till it reached the town of Heliopolis. 'In that city,' says another writer, whose account is not quite the same as the story told by the first 'in that city there is a temple made round, after the shape of the Temple at Jerusalem. The priests of that temple date their writings from the visits of the Phoenix, of which there is but one in all the world. And he cometh to burn himself upon the altar of the temple at the end of five hundred years, for so long he liveth. At the end of that. time the priests dress up their altar, and put upon it spices and sulphur, and other things that burn easily. Then the bird Phoenix cometh and burneth himself to ashes. And the first day after men find in the ashes a worm, and on the second day they find a bird, alive and perfect, and on the third day the bird flieth away. He hath a crest of feathers upon his head larger than the peacock hath, his neck is yellow and his beak is blue; his wings are of purple colours, and his tail yellow and red in stripes across. A fair bird he is to look upon when you see him against the sun, for he shineth full gloriously and nobly.'

THE PHNIX

It is very hard to believe that the man who wrote this had not actually seen this beautiful creature, he seems to know it so well, and perhaps sometimes he really fancied that one day it had dazzled his eyes as it darted by. The Phoenix was a living bird to old travellers and those to whom they told their stories, although they are not quite agreed about its habits, or even about the manner of its death. Sometimes, as we have seen, the Phoenix has a father, sometimes there is only one bird. In general it burns itself on a spice-covered altar; but. according to one writer, when its five hundred years of life are over it dashes itself on the ground, and from its blood a new bird is born. At first it is small and helpless, like any other young thing; but soon its wings begin to show, and in a few days they are strong enough to carry the parent to the city of Heliopolis, where, at sunrise, it dies. The new Phoenix then flies back home, where it builds a nest of sweet spices cassia, spikenard and cinnamon; and the food that it loves is another spice, drops of frankincense.

PUMAS AND JAGUARS IN SOUTH AMERICA

No one can have read Captain Mayne Reicl's stories about America without being struck by the part played in them by an animal called the 'painter,' which is of a tawny colour, with a black stripe down its back. Now the 'painter' is really the panther, and the panther is the creature that we call the puma, which, next to the jaguar, is the biggest of all the American cats, and has a wider range than any other mammal. The puma is to be met with in British Columbia, or in the Adirondack mountains not far from New York State; it is to be seen in the hot unhealthy swamps that lie along the northern shores of the Gulf of Mexico; it lies in wait for its prey in the river forests of the Amazon and the Orinoco; it tracks the wild and cunning huanaco ten thousand feet high on the Andes, and it is the dreaded enemy of colts and sheep on the cattle runs of the Argentine Republic. With wonderful skill it makes the best of circumstances; if horses, its favourite food, are not to be had, it puts up with ostriches; if it happens to live in Mexico, or Arizona, its makes its dinner off wild turkeys; further north still, the puma will be content with porcupines or even snails, while if its chosen haunts along the river banks of the Amazon or the Orinoco are overwhelmed by a sudden inundation, it takes to the trees and feasts upon monkeys.

As sometimes occurs in families, the puma has a particular hatred for its cousin the jaguar, and seldom indeed does it fail to get the better in any fight. It also has a violent dislike to dogs, and in South America can never see one without flying out to attack it, while the grizzly bear is its deadly foe. But, on the other hand, in the great continent of South America it shows its best qualities. It loves man, and even when attacked by him will not defend itself, while in puma-haunted districts children may even sleep all night alone, without fear of harm. And not only children, for travellers tell us a puma has never been known to attack a sleeping man.

It is a great pity that pumas are so fond of killing tame and useful beasts, as they have many delightful qualities as pets. Pumas are very playful, and very affectionate and gentle to people and children; but they are rapidly being hunted down, as farmers find it quite impossible to keep any cattle in their neighbourhood. Between their courage and their wonderful powers of jumping, no animals are safe from them. Some witnesses have declared that pumas have been seen, when pursued by dogs, to spring a clear twenty feet into the air for shelter in a tree, while another leap of forty feet was measured on the ground. In Patagonia, a farmer who had suffered much from a puma's appetite shut all his sheep into a huge fold, surrounded by a wooden paling fifteen feet high. The only entrance was by a six-foot gate, and, to make all secure, men and dogs were told off to watch. But the puma was too clever for them all! He seized his chance when any clouds came up to make the darkness thicker, and every morning one sheep at least was found with a dislocated neck, and its breast eaten, for this is the way a puma always kills its prey, and, except when very hungry, it never eats the whole carcass. One night, the naturalist who tells the story was passing by the gate, when the robber sprang right over his head, but it was too dark to give chase, so the puma got away safely. Afterwards, it was found that it had been in the habit of hiding till dark in the pen with some calves, which it never tried to touch, as it knew it was sure of the sheep.