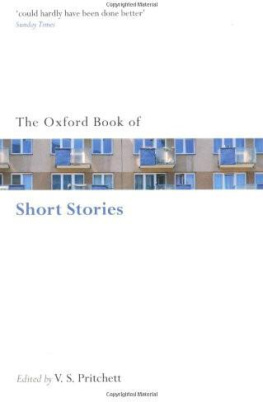

A Man of Letters

SELECTED ESSAYS

V. S. PRITCHETT

For My Wife

If, as they say, I am a Man of Letters I come, like my fellows, at the tail-end of a long and once esteemed tradition in English and American writing. We have no captive audience. We do not teach. We are rarely academics though we owe a great debt to scholars. We earn our bread and butter by writing for the periodicals that have survived. If we have one foot in Grub Street we write to be readable and to engage the interest of what Virginia Woolf called the common reader. We do not lay down the law, but we do make a stand for the reflective values of a humane culture. We care for the printed word in a world that nowadays is dominated by the camera and by scientific, technological, sociological doctrine. We still believe, with Dostoevsky, that without art a man might well feel that his life was not worth living. We ourselves have written novels, short stories, biographies, works of travel. Some of us are poets. And we know that literature is rooted in the daily life of any society but that it also springs out of literature itself. The difference between the traditional Man of Letters and us survivors today is that what we have to say must be done in a couple of columns whereas the Victorians look at Henry James could go on in the Monthlies and Quarterlys for dozens of pages. When, at the beginning of World War II I was asked to write a page under the title of Books in General, for the New Statesman, paper was rationed in Great Britain and I was soon cut down from 1850 to 1800 words. It was a training in the allusive and laconic style that has remained with me for the fifty years I have given to writing essays such as these in this book.

This selection is taken from pages I have contributed to the New Statesman, the New Yorker, and the New York Review of Books and some from my first book of essays during the War, now out of print. It is strange to look back at the early ones and to remember reading, say, the four volumes of Clarissa in one week or perhaps Gil Bias, Balzac or Turgenev the next, as I travelled by slow trains packed with troops (and from air-raid warning to air-raid warning), to shipyards and factories in the North to report about the war effort and to write between the hours of my comic duties with the local militia and fire-watching. Why was I asked to write on these authors? Contemporary writing had stopped. We were left with the major and the minor masters of the past. Air-raid shelters for the mind? Not at all. These authors, we found to use a phrase common at the time had also lived in times of transition, in or between wars. They were embalmed in their genius but had lived, as we did, in a changing society. Look back and we could see the rogue turning into the Puritan and the Puritan revealing a hidden and even exuberant imagination. We could see Scott evoking a splitting society. We saw literature growing out of life and the common experience. I had fortunately read such books when I was a youth. I had also earned my living in trades that had brought me close to people more diverse than the literary. I was not a product of Eng.Lit. I had never been taught and, even now, I am shocked to hear that literature is taught. I found myself less a critic than an imaginative traveller or explorer a slow reader too moving from sentence to sentence, pausing to see the view and the writer arriving at the clinching detail. I had a double contact with human nature, first as a writer crossing frontiers in Ireland, France, Spain and the Americas and as a traveller in the use of writing in these countries. I was travelling in literature.

V. S. PRITCHETT

Contents

British

American

European

An Anatomy of Greatness

There are two books which are the perfect medicine for the present time: Voltaires Candide and Fieldings Jonathan Wild. They deal with our kind of news but with this advantage over contemporary literature: the news is already absorbed, assumed and digested. We see our situation at a manageable remove. This is an important consolation and, on the whole, Jonathan Wild is the more specific because the narrower and more trenchant book. Who, if not ourselves, are the victims of what are called Great Men? Who can better jump to the hint that the prig or cut-purse of Newgate and the swashbuckler of Berchtesgaden are the same kind of man and that Caesar and Alexander were morally indistinguishable from the gang leaders, sharpers, murderers, pickpockets from whom Mr Justice Fielding, in later years, was to free the City of London? Europe has been in the hands of megalomaniacs for two decades. Tyranny abroad, corruption at home that recurrent theme of the eighteenth-century satirists who were confronted by absolute monarchy and the hunt for places is our own. Who are we but the good with a small middle-class g and who are they but the self-elected leaders and the Great? And Jonathan Wild has the attraction of a great tour de force which does not shatter us because it remains, for all its realism, on the intellectual plane. Where Swift, in contempt, sweeps us out of the very stables; where Voltaire advises us not to look beyond our allotments upon the wilderness humanity has left everywhere on a once festive earth, Fielding is ruthless only to the brain. Our heads are scalped by him but soul and body are left alive. He is arbitrary but not destructive. His argument that there is an incompatibility between greatness and goodness is an impossible one, but of the eighteenth centurys three scourgers of mankind he is the least egotistical and the most moral. He has not destroyed the world; he has merely turned it upside down as a polished dramatist will force a play out of a paradox:

contradicting the obsolete doctrines of a Set of Simple Fellows called, in Derision, Sages or Philosophers, who have endeavoured as much as possible to confound the Ideas of Greatness and Goodness, whereas no two Things can possibly be more distinct from each other. For Greatness consists in bringing all Manner of Mischief on Mankind, and Goodness in removing it from them.

Jonathan Wild is a paradox sustained with, perhaps the strain, but above all, with the decisiveness, flexibility and exhilaration of a scorching trumpet call which does not falter for one moment and even dares very decorative and difficult variations on the way to its assured conclusion. When we first read satire we are aware of reading against the whole current of our beliefs and wishes, and until we have learned that satire is anger laughing at its own futility, we find ourselves protesting and arguing silently against the author. This we do less, I think, in reading Jonathan Wild than with Candide or Gulliver. If there is any exhaustion in Jonathan Wild it does not come from the tussle of our morality with his. There is no moral weariness. If we tire it is because of the intellectual effort of reversing the words great and good as the eye goes over the page. Otherwise it is a young mans book, very vain of its assumptions and driven on with masterly nonchalance.

To the rigidity of his idea Fielding brought not only the liveliness of picaresque literature but, more important, his experience as a playwright. Of its nature satire deals in types and artifices and needs the schooling of the dramatist, who can sweep a scene off the moment the point is made and who can keep his nimble fingers on a complicated plot. Being concerned with types, satire is in continual need of intrigue and movement; it needs tricks up the sleeve and expertness in surprise. We are distracted in