EARLY BIRD BOOKS

FRESH EBOOK DEALS, DELIVERED DAILY

LOVE TO READ ?

LOVE GREAT SALES ?

GET FANTASTIC DEALS ON BESTSELLING EBOOKS

DELIVERED TO YOUR INBOX EVERY DAY!

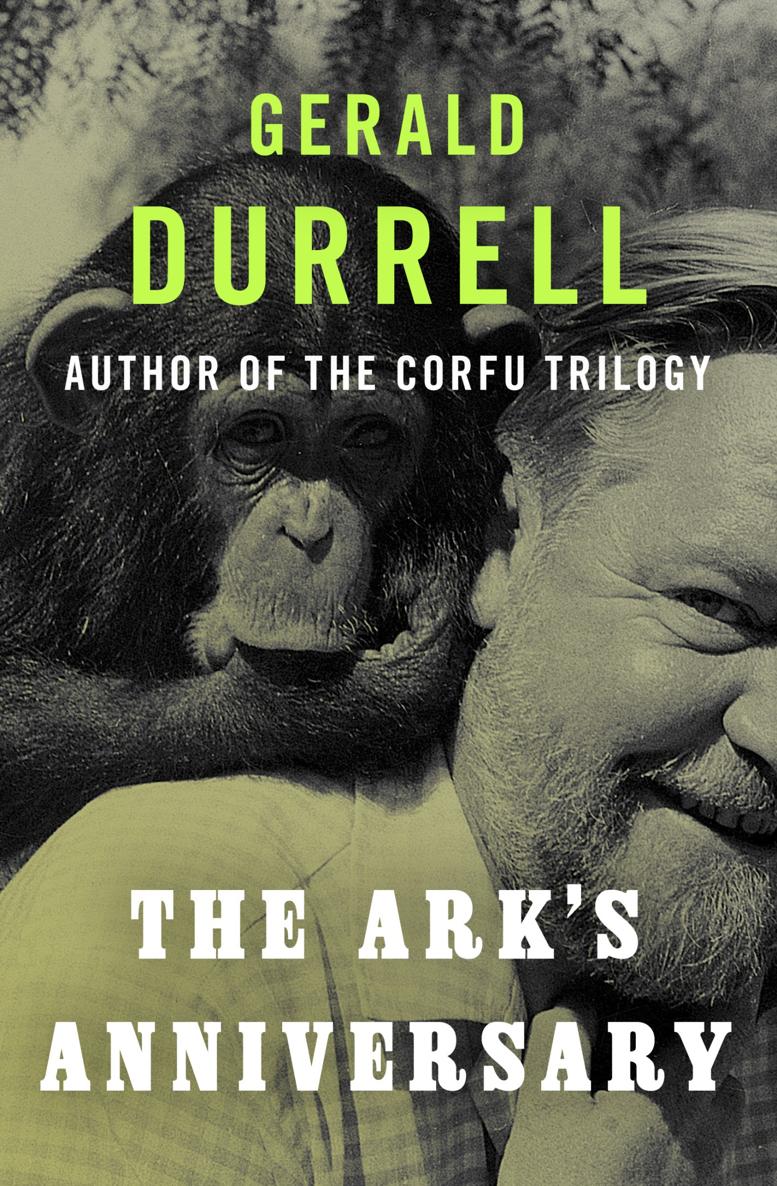

The Arks Anniversary

Gerald Durrell

THIS BOOK IS FOR

T HOMAS L OVEJOY

WITH WHOSE HELP , HUMOUR AND HARD WORK WE HAVE ACHIEVED MUCH

Contents

Foreword by H.R.H. The Princess Royal

My association with the Jersey Wildlife Preservation Trust began, as it has done for thousands of others, on a train with a book written by its founder, Gerald Durrell. He has the ability, shared with few other authors, to extravasate a spontaneous explosion of mirth that surprises the reader as much as it does the unsuspecting travelling companion. To eat ones sandwich while reading Mr Durrell is to court still greater embarrassment.

I realize now that he uses his own exclusive brand of anthropomorphism to build relationships and therefore, inevitably, bonds between his reader and other animal species. I also recognize that he employs this singular gift to reach a multiple audience, a strategy he continues to harness to great effect in other ways.

I have now visited the J.W.P.T. several times and while each is memorable in its own way, none stands out as being more significant than that of the Trusts 21st and the Zoos 25th joint anniversary in 1984, when I was asked to open the International Training Centre for the Conservation and Captive Breeding of Endangered Species.

You will read that, via graduates of this Training centre, the Trusts influence and activity is spreading across the globe on a scale wholly disproportionate to its modest headquarters in the Channel Islands.

I believe that it behoves all of us, as guardians of the living world we have inherited, to see that we pass on this priceless inheritance to the next generation. In order to do that, however, we must understand why it is necessary and how to do it. One of the most exciting developments, growing out of a realization that captive breeding can, of itself, create an opportunity for learning, is the adaptation of the breeding centre to provide a focus for public education.

I am delighted that The Princess Royal Pavilion in Jersey will provide one such opportunity, so that over 350,000 visitors to our headquarters each year can be taught the philosophy behind the Trusts objectives. Of at least equal significance is the first Zoo Educators Course which will teach zoo staff from developing countries how well maintained animal collections can be utilized to impart the principles of wildlife conservation.

Once again Gerald Durrell and his small team seem to have found a way to reach an international audience of barely estimable numbers.

To say that one person, or indeed one organization, cannot do it all, is a truism. But I feel bound to suggest that if everyone and every biologically based institution did as much as Mr Durrell and his Trust to help stitch and darn our planets threadbare ecology, there might be fewer holes in our natural defences than there are today.

All Gerald Durrells books are worth waiting for. This one is no exception and will, I hope, serve to convince many more people that where there is a will and a well thought out way, the impossible becomes commonplace and even miracles dont take quite so long.

A Word in Advance

I do not think it possible for many people at the age of six to be able to predict their future with any accuracy. However, at that age I felt confident enough to inform my mother that I intended to have my own zoo and moreover, I added magnanimously, I would give her a cottage in the grounds to live in. If my mother had been an American parent, she would probably have rushed me to the nearest psychiatrist; however, being fairly phlegmatic, she merely said she thought that it would be lovely and promptly forgot all about it. She should have been warned since, from the age of two, I had been filling matchboxes and my pockets with a wide variety of the smaller fauna that came my way, so the progress from a matchbox to a zoo could have been predicted. It is nice to record though that, before she died, I had fulfilled my promise and taken her to live in my zoo, not in a cottage but in a manor house.

Looking out of the windows of my first-floor flat in Les Augres Manor is an unpredictable operation and would give any psychiatrist pause for thought. From the living-room windows, for example, you are suddenly transfixed while in the middle of pouring out a refill of pink gin for your guest by the sight of the Przewalski horses running their variation of the Derby around their paddock, and you watch them breathless, wondering which muscular, pinky-brown animal is going to win. Meanwhile, with no explanation for your sudden inhospitable immobility, your guest is left, as it were, unquenched.

In the dining room worse befalls. Your carving is brought to a halt in mid-joint because you have let your gaze stray out of the window and have caught sight of the Crowned cranes doing their courtship dance. Their lanky legs are thrown out at the most unanatomical angles as they pirouette around like bedraggled, failed ballet dancers, leaping high in the air, dextrously juggling twigs as love tokens and uttering loud, rattling, bugle-like cries.

Modesty prevents me from relating what can be seen from the bathroom window when the Serval cats are loudly and apparently agonizingly in season, moaning their hearts out, screaming with love and lust. However, worse far worse befalls you in the kitchen should you lift your eyes from the stove and let them wander. You are confronted by a large cage full of Celebes apes, black and shiny as jet, with rubicund pink behinds shaped exactly like the hearts on valentine cards, and all of them indulging in an orgy which even the most avant-garde Roman would have considered both flamboyant and too near the knuckle. Close contemplation of such a spectacle can lead to disaster, such as irretrievably burning lunch for eight people as they arrive to partake of it. This happened to me on one occasion and I discovered that even friends of long standing do not take kindly to boiled eggs when they have been churning up their gastric juices in expectation of a five-course gourmet meal.

There are even worse things. One morning I was entertaining a coterie of extremely ancient and wobbly octogenarian conservationists, who were making steady inroads into my sweet sherry. I was just about to suggest (while they had what wits they possessed still about them) that we sallied forth to look at the animals, when I glanced out of the window and saw, to my horror, slouching through the forecourt among the spring flowers, Giles, our biggest, most hirsute and potentially lethal Orang utan. He looked like a gigantic walking hearthrug of orange and blond hair and he had that lurching side-to-side movement thought to be the prerogative of sailors who have spent many years on the bosom of the ocean and an equal number of years on the rum. I was trapped and for the next hour I had to ply my geriatric acquaintances with more and more sweet sherry and they got progressively more and more inebriated. At last the happy news came that Giles had been darted and returned to his rightful quarters, and I could get rid of my by now extremely convivial conservationists. But my blood ran cold at the thought of what would have happened if I had ushered them (all the worse for the application of the Demon Drink) out of the front door at the precise moment when Giles came shambling into the forecourt.