Harold Lamb - Swords from the East

Here you can read online Harold Lamb - Swords from the East full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2010, publisher: U of Nebraska Press, genre: Detective and thriller. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Swords from the East

- Author:

- Publisher:U of Nebraska Press

- Genre:

- Year:2010

- Rating:4 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Swords from the East: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Swords from the East" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Swords from the East — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Swords from the East" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

vii

xi

xiii

i

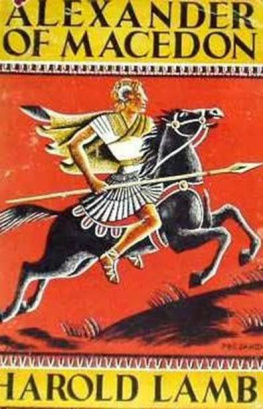

Harold Lamb wrote that he'd found something "gorgeous and new" when he discovered chronicles of Asian history in the libraries of Columbia University. He remained fascinated with the East thereafter, which is evident from his first stories of western adventurers in Asia to the last book published before his death in 1962, Babur the Tiger. All of his popular fiction is anchored in Asia, whether it be the cycle of Khlit the Cossack, descended from the Tatar hero Kaidu, or Durandal's Sir Hugh of Taranto, who travels into Asia during the conquests of Genghis Khan, or even the adventures of Genghis Khan himself, as related in "The Three Palladins" in this volume.

In this age, both the 192os and the 1120s are remote to us. It might seem odd that a story set in one time can sound old-fashioned and quaint while one set in the other does not, especially when they were crafted by the same writer, but looking over the whole of Lamb's work, one reaches an inescapable conclusion: it is when Lamb looked backward that his prose sprang to life. His historical characters are far better realized than his modern heroes. Passion for his subject was writ large in every historical story. Lamb loved what he was writing, and it shows, most especially in the tales crafted for Adventure magazine, where editor Arthur Sullivan Hoffman gave him free rein to write what he wished. Even today, some eighty or ninety years after their creation, no matter changed literary trends and conventions, these stories beguile with the siren song of adventure. Lamb's polished and surprisingly modern sense of plotting and pacing is in full evidence in every story in this volume.

Lamb's first real writing success came from sending characters into Asia to adventure, but before too long he tried his hand at writing of adventurers who were Asian. (Khlit, of course, is of Asian descent, but he would have been more "western" and familiar to his first readers than those characters he encounters through his wanderings. Lamb tried his hand at several shorter tales with Mongolian protagonists, including "The Wolf-Chaser," a story of a last stand in Mongolia that proved so inspiring to a young Robert E. Howard that Howard outlined it and took a crack at drafting a version of the story himself.*

Lamb then tackled a novel of a Mongol tribe's perilous migration east, with a westerner as one of the main-though not the only-protagonists. Before too much longer, though, he drafted what he might always have longed to do, given his abiding fascination with Genghis Khan. The result was "The Three Palladins," which explores the early days of Temujin through the eyes of his confidant, a Cathayan prince. On first reading it as a younger man, I was for some reason disappointed that it had nothing to do with Khlit the Cossack, and I failed to perceive its worth. Like almost all of Lamb's Adventure-era fiction, it is swashbuckling fare seasoned with exotic locale. There is tension and duplicitous scheming on every hand. The author seems to have had almost as much fun with the characters as the reader, for some of them turn up in other stories-the mighty Subotai, and the clever minstrel Chepe Noyon in the Durandal cycle and "The Making of the Morning Star," which is included in Swords from the West (Bison Books, 2009. And Genghis Khan, of course, as a shaper of events and mythic figure, haunts much of Lamb's fiction, affecting even the Khlit cycle set hundreds of years later, most famously in one of the best of all the Khlit the Cossack stories, "The Mighty Manslayer," which appears in Wolf of the Steppes (Bison Books, 2006).

Lamb was fortunate to have become established as a writer of both screenplays and history books by the time the Great Depression hit. Adventure, his mainstay, was no longer published as frequently or capable of paying as well. Lamb's fiction began to be printed in the slicks-Collier's and, a little later, the Saturday Evening Post (among a handful of similar magazines-where he still wrote short historicals as well as contemporary pieces. Among the later work included in this volume is a deft little mystery adventure titled "Sleeping Lion," with none other than Marco Polo as one of the primary characters, the other being a Tatar serving girl. Unfortunately, Collier's printed this story without its middle third. What remains is included. Sadly, the original is long since lost.

There also exist two curious pieces from Lamb's Adventure days: "The Book of the Tiger: The Warrior" and "The Book of the Tiger: The Emperor." Together they tell the story of Babur, the Tiger, first Moghul emperor, mostly transcribed and condensed from Babur's fascinating autobiography. They presage Lamb's later books like Alexander the Great and Theodora and the Emperor, where the narrative is a history that occasionally drifts into fiction. Those volumes have never been among my favorites (Hannibal, both volumes of The Crusades, and March of the Barbarians top my list), but I'm fond of these Babur pieces even if they sometimes sound more like summaries than fully realized stories. Lamb captured the tone of a truthful and engaging historical character. The amount of luck hand the stupidity of his fellow mangy involved in Babur's survival through adversity is difficult to believe. Were I to invent such a story and submit it to a publisher, it would be dismissed out of hand as preposterous, but this one seems to be true! Lamb later turned to other Asian characters as protagonists and narrators, and you can find many of those tales in Swords from the Desert Bison Books, 2009 ~.

Much of Lamb's fiction output revolved around conflicts generated by the colliding motivations of his characters and their cultures. Through most of the stories in this book, the physical environment takes on an antagonistic role as well, for the people in these tales of high Asia must contend with steep mountain passes, blinding snows, searing deserts, and ice-choked rivers. While justice may win out or protagonist triumph, the victories seem transitory, to be celebrated briefly before the candles are extinguished and the central characters shuffle off the stage. Kings, kingdoms, and heroes fall and fade to memory; nothing is eternal but the uncaring miles of mountain and steppe and the shifting northern lights that shine above them.

That life is sweet and Lady Death ever eager for the embrace of heroes is a theme that can be found in Lamb's fiction from the very beginning, but readers may note that all of these tales-even the relatively light "Azadi's Jest"-are infused with a certain bleakness more marked than usual. We can exult in the adventure, but we are reminded to savor our sand castles before time and tide sweep them away.

If you enjoy these stories of Mongolia, you have not far to look for more of Lamb's writing on the subject; his history and biography books are still held in many public libraries. Harold Lamb's first book, a biography of Genghis Khan, has fared better than any of his other works, remaining in print since 1927. Lamb himself thought this was peculiar because he believed his later books were better written. While Genghis Khan is a good read, I tend to agree: Tamerlane is a strong book, and March of the Barbarians is riveting. The latter title does little to reveal the quality within, for March is an in-depth history of the complex inner workings of the Mongol empire, written when Lamb was more experienced and had the financial wherewithal-as well as the clout with publishers-to take the time for extensive research. His Genghis Khan proposal had been approved by the publisher only so long as he could write the book in two weeks, a demanding request even for someone intimately familiar with the subject matter. March of the Barbarians covers the same material as Genghis Khan in richer detail, and then goes on to describe the great Khan's successors with the same care. Frederick Lamb, Harold's son, named it the favorite of all his father's writing.

Next pageFont size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Swords from the East»

Look at similar books to Swords from the East. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Swords from the East and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.