BY THE SAME AUTHOR

A Writers Life (2006)

The Gay Talese Reader (2003)

The Bridge (revised and updated) (2003)

The Literature of Reality (with Barbara Lounsberry) (1996)

Unto the Sons (1992)

Thy Neighbors Wife (1980)

Honor Thy Father (1971)

Fame and Obscurity (1970)

The Kingdom and the Power (1969)

The Overreachers (1965)

The Bridge (1964)

New York: A Serendipiters Journey (1961)

THE SILENT SEASON

OF A HERO

The Sports Writing of Gay Talese

Edited by Michael Rosenwald

Compilation copyright 2010 by Gay Talese

Introduction copyright 2010 by Gay Talese

Section introductions copyright 2010 by Michael Rosenwald

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles or reviews. For information address Walker & Company, 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, New York 10010.

The articles on which a portion of this book is based originally appeared in the New YorkTimes, and to the extent they are reprinted here, they are reprinted with permission.

Published by Walker Publishing Company, Inc., New York

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

The silent season of a hero : the sports writing of Gay Talese / edited by Michael Rosenwald.1st U.S. ed.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references.

ISBN 978-0-8027-7753-9 (paperback)

1. Talese, Gay. 2. SportswritersUnited States. 3. JournalistsUnited States. 4. SportsUnited States. I. Rosenwald, Michael. II. Title.

GV742.42.T38S55 2010

070.4'49796dc22

2010024507

First published by Walker Books in 2010

This e-book edition published in 2010

E-book ISBN: 978-0-8027-7839-0

Visit Walker & Companys Web site at www.walkerbooks.com

CONTENTS

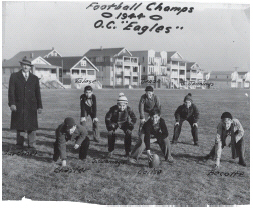

G A Y T A L E S E G R E W up in Ocean City, N.J., a seaside resort town a couple of hours by car from New York City. His father was a tailor and his mother sold dresses, and they doted on their customers at their small shop, Talese Town Shop, located just underneath the familys apartment. Talese was an outsider in school, not unlike his parents, who were Catholic Italian-Americans making their lives in an old Protestant town. While his classmates dressed in mackinaw jackets, Talese wore handsome fitted clothesjacket and tie, alwaysthat his father had stitched together at the shop. Decades later, at a class reunion, Talese remembers classmates told him that they had found him aloof and quirky and in another world. Talese got lousy grades. He even flunked English. I really had nothing going on, he felt.

His outlook changed one day when Lorin Angevine, the editor of the weekly town newspaper the Sentinel-Ledger and a regular customer at the store, suggested to Taleses father that his wayward son should submit articles to the paper. Talese had become interested in short stories after discovering a Maupassant collection in his house, and that led to him penning articles here and there for the high school paper. He enjoyed seeing his byline in print, so he went to see Angevine, who offered him a column called High School Highlights at a salary of ten cents per column inch. The first break I had in life was working for the town weekly because it gave me an excuse for a career future, Talese says. I didnt have a career future. I wasnt going to be a tailor because the tailoring business was dying.

Talese, an outsider to his schools social scene, attended dances as a reporter rather than a young man with a date, chronicling who wore what and who strolled in on the arm of the football captain. Though he could hit a baseball his contributions to the towns sporting scene came primarily at his typewriter. He wrote a popular column called Sportopics. Looking at these early efforts there are hints of Taleses lifelong obsession, and compassion, for outsiders and losers. Short Shots in Sundry Sections, from Dec. 23 1948, is about a six-foot seven-inch freshman basketball player taking the court for the first time. Clueless about the game, but towering over the other players, his coach instructs the awkward giant to stand under the basket and wait for teammates to toss him the ball. He missed lots of passes and didnt score, but hes still learning, Talese wrote, and willing.

Talese was rejected by every college in the region. A customer of his fathers who graduated from the University of Alabama made a few phone calls to the admissions office in Tuscaloosa, and Talese was accepted there a few weeks later, not even knowing he had applied. On the train ride down, Talese read a novel by Irwin Shaw, one of his favorite writers. Though he wasnt elected sports editor of the Crimson-White until his junior year, as a journalism major he immediately resisted his teachers efforts to drill into his writing the who-what-when-where-why formula of daily journalism by incorporating into his stories the tools of a fiction writerscene, characters, dialogue, narrative.

In his feature stories for the Crimson-White and later in his column Sports Gay-zing, Talese cared little about final scores and more about the characters playing the games. The column, he once wrote, was inspired to the point of plagiarism by the bittersweet romanticism of Irwin Shaws short stories in the New Yorker and Red Smiths lyrical musings on athleticism in the New York Herald-Tribune . As a rule, losers were always more attractive subjects than winners, and in these portraits the now singular Talese voicedeft, precise, gentle, sometimes formal, sometimes wittybegins appearing. In a story about a devastating football team loss, Talese described the players in the locker room as dressed in shorts, or in towels, or in nothing. About the first football practice one season, Talese wrote: Under hail, a cold wind, a 30-degree temperature Saturday afternoon, Coach Harold (Red) Drew gently tooted the whistle at 3:30 P.M. and 80 huge hunks of Alabama scholarships began to smash and lash at one another. Talese graduated in 1953, returning north and landing a copyboy job at the New York Times.

MR

I N J A N U A R Y O F 1956, Lt. Gay J. Talese, stationed at the Public Information Office of the Army in Fort Knox, received a letter from New York Times sports editor Raymond J. Kelly promising that when he finished his Army service you will come back to the Sports Department as a reporter on trial. Talese had done well as a copy boy at the Times after graduating from the University of Alabama, and he had impressed his superiors with his writing before the Army commissioned him. I have no doubts of your success, the letter continued. You are a first-rate writer, and I hope that in time you will become one of the best men on my staff. Meanwhile, keep yourself informed on sports news.

Upon arriving for duty as a sportswriter, Talese took his notebook in the opposite direction of news. He avoided assignments that had the possibility of landing on page one, where he knew that news dominated the story. Talese wanted to form his own storiesto write short stories that happened to be true about unknown characters being ignored in the press and by the great nonfiction writers of the day.

He found subjects like Ruby Goldstein, a boxing referee who was the most lonely guy in boxing, cutting off all his friends in the fight game to maintain his integrity, and a troupe of midget wrestlers who rode to work in a Cadillac that comfortably seats eight midgets and a driver. Talese constructed his factual short stories with the formal yet whimsical voice that has come to define his work. Roller derby star Gerry Murray was a curvesome woman pushing 40 with the gentility of a waterfront bouncer. About Mike Gillian, a horseshoe maker, Talese wrote: Many of the prize animals that have been running around Madison Square Garden this week have been purchasing Gillians footwear for years.

Next page