Table of Contents

Salutations to Maa Shakti, the One who powers my pen.

Thank you, Maa, for your abundant blessings.

I am nothing without you.

Yatha ahu vairyo atha ratush ashat chit hacha

Vangheush dazda manangho shyothananam angheush mazdai

Kshathrem cha ahurai a yim daregobyo dadat vastarem.

Yasna 27:13, Zend Avesta

CONTENTS

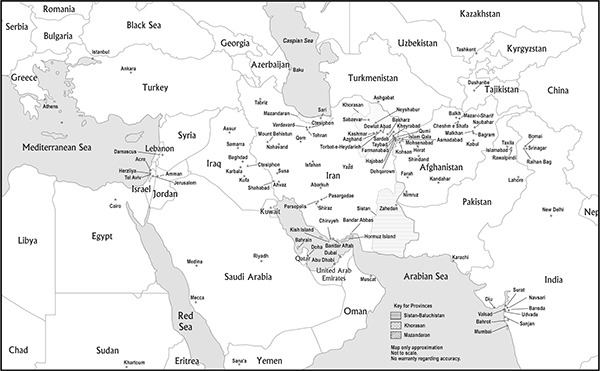

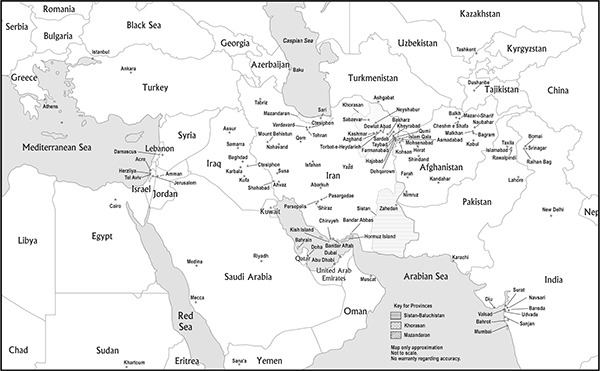

This book is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places and events are either the products of the authors imagination or used in a fictitious manner. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, or actual events is purely coincidental. Historical, religious or mythological characters; historical or legendary events; or names of places are always used fictitiously. No claim regarding historical or theological accuracy is either made or implied. Historical, religious or mythological characters, events or places, are always used fictitiously and deviations from the accepted record also occur within the narrative. Images and maps are for illustrative purposes only and are presented without any claim of accuracy.

THE FIFTY-FIVE-YEAR-OLD MAN made his deliberate way up to the stage. He was dressed in a no-fuss blue blazer and khaki trousers, a deep-red tie matching the scarlet square that peeped from his pocket. The smile on his face was a friendly one, softening any severity of feature and signalling a singular approachability. Quite unlike someone who had won the Kettering Prize just last year. He walked up to the podium slowly and looked at the audience. He swept his gaze over the politicians, academicians, businessmen and bureaucrats who were applauding.

The din subsided the moment he placed his hands on the lectern and leaned into the microphone. In the expectant silence that followed, he began, Some four centuries before Christ, the Greek Hippocrates told his pupils, Declare the past, diagnose the present, foretell the future. But then, he was the father of medicine. Had anyone asked me to foretell the future when I was a young graduate from Stanford, Id have been stumped. And had anyone then pointed out to me how inextricably the past is linked to our future, I would have laughed.

The hall at Oxford could have been a museum, each wall lined end to end with portraits of renowned monarchs, artists and scientists, each bathed in the light filtering in through exquisite stained-glass windows. The ceiling was a flawless example of a sixteenth-century hammerbeam roof, the timber, untampered by veneer, aglow. It could have been the interior of a vast Gothic cathedral. He took it all in without appearing to look and paused reverently.

But here we are in the present, he picked up his theme, celebrating a future that has been fashioned from our past. And why? Because, at every point in experience, history, philosophy, science and our lives ahead do intersect. I have come to believe, as I hope you will, that it is foolish to describe them as discrete entities. I declare that we have been misled on that. Any scientist worth his lab coat has to be a philosopher. Just like the greatest philosophers have thrown their weight behind science.

In Japan, continued the speaker, there lived a great Zen master during the Meiji era. One day, a scholar came to him for an explanation of his philosophy. The master poured the visitor a cup of tea from a kettle. He continued to pour even after the cup was full. The scholar saw that the tea was spilling over the cup and said, Stop, Master. Theres no more room for tea in the cup.

The speaker paused, allowing the image to sink in. Then he continued, The Zen master smiled at his guest and said, The cup has a limited capacitylike you. You have filled yourself with opinions, beliefs, prejudices and attitudes before coming to me. How can I possibly show you Zen, unless you are willing to empty your cup first? Over the past decade, I have tried my best to be that proverbial empty cup.

Indian gurus have said that true wisdom lies in knowing that one knows nothing. I am grateful to the universe for having taught me that. I proudly stand before you today as the man who knows nothing. And I raise a toast to my friend Jim Dastoor, who is dead.

The audience rose to their feet as one, in a long, rapturous ovation. Still clasping the lectern, the Kettering Prize awardee examined the cufflinks on his shirtsleeves. He no longer sensed the publics adulation as his mind travelled back to the friends he had lost in his quest.

THE MAN IN uniform had not known that pulling a trigger was so easy.

That rainy evening, he had walked with a group of security guards along Great Russell Street in the fashionable and busy Bloomsbury district of London. They side-stepped the vehicle-distancing bollards and walked through the gate of a black iron fence. Then they cut across a yard to reach a neoclassical building dating from the Georgian era. Over 300 men and women were part of the elite unit that guarded the British Museum at all times.

The museum housed eight million objects within an expanse of 75,000 square metres. On most days, around 17,000 visitors walked into its hallowed halls. Established in 1753, the place was often in the news for all the wrong reasons. After all, most of the exhibits had been sourced from around the world when Britannia reigned. Britains colonial past had come under severe scrutiny, one reason being the looting of national treasures from conquered lands.

Not that this knowledge dimmed the curiosity of its gawking visitors.

The museum hosted some of the worlds most priceless objects. These included the Rosetta Stone, the key to deciphering Egyptian hieroglyphs. There was the colossal granite head of Amenhotep III, the pharaoh who ruled Egypt between 1390 and 1325 BCE. Another precious item was the Sutton Hoo Ship burial helmet worn by an East Anglian king from the seventh century CE. And then there was the most famous item of all, the ancient Cyrus Cylinder. On its clay surface was written, in Akkadian cuneiform, a declaration by the great Achaemenid king, Cyrus, in the sixth century BCE.

This evening, after a quick but thorough inspection, the group of guards crossed the Queen Elizabeth II Great Court with its high steel-and-glass lattice roof. The area had once been open to sky but had been redeveloped as a covered enclosure sheltering the treasures in the surrounding galleries.

One of the guards from the group broke away covertly and headed towards Room 52, one of the several galleries that dotted the museum. Once he was within spitting distance of 52, he hid himself in a supply closet that he had identified some days earlier. He had already obtained the schematics of the museum that showed locations of the security cameras in the area. That had been easy enough, given his access to the security command centre. The entire museum was a high-security zone, integrating cameras, alarms, access control and a digital radio system.

Inside the closet, the man sat and waited.

By 5 pm the security team began escorting visitors out while courteously thanking them for having come. An hour later, caterers entered. By 7 pm, the entire Great Court had been transformed by an elegant arrangement of damask-covered tables, flowers and dinnerware for a corporate event. The wining and dining wrapped up by 10 pm.