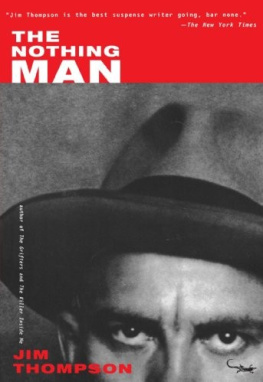

WANTED:

Unencumbered woman for general work in out-of-town home. Forty to forty-five; able to wear size 14 uniform. Excellent wages, hours. Box No."I'll let you write in the box number," I told the girl behind the counter. "Have to let you do something to earn your money."

She smiled, kind of like an elevator boy smiles when you ask him if he has lots of ups and downs. "Yes, sir. What is your name, please?"

"Well," I said, "I'm going to pay for the ad now."

"Yes, sir," she said, just as much as to say you're damned right you're going to pay now. "We have to have your name and address, sir."

I told her I was placing the ad for a friend, "Mrs. J.J. Williamson, room four-nineteen, Crystal Arms Hotel," and she wrote it down on a printed slip of paper and stabbed it over a spike with a lot of others.

"That runs one word over three lines. If you like, I think I can eliminate a-"

"I want it printed like it stands," I said. "How much?"

"For three days it will be two dollars and forty-four cents."

I had a dollar and ninety-six cents in my overcoat pocket-exactly enough if Elizabeth had figured things right. I pulled it out and laid it on the counter, and fumbled around in my pants pocket for some change.

I found a quarter, two nickels, and a few pennies. I dropped them into my coat as soon as I saw they weren't enough, and reached again. The girl stared at my hands-the gloves-her eyebrows up a little.

I came out with a half dollar and slid it across to her.

"There," I said, "that makes it."

"Just a minute, sir. You have two cents change coming.

I waved my hand at her to keep it. I didn't want to try to pick up those pennies with my gloves on, and something told me she'd make me pick them up. I wanted to get out of there.

She hollered something just as the door closed, but I didn't turn around. I hit the street and I kept right on walking without looking back.

I guess I must have gone a dozen blocks, just walking along blind, before I realized I was being a chump. I stopped and lighted a cigarette, and saw no one was following me. It began to drift in on me that there really wasn't any reason why anyone should. I felt like kicking myself for letting Elizabeth plan the thing.

She'd insisted on my wearing gloves, which, I could see now, was a hell of a phony touch. She'd had me print out the ad in advance on a piece of dime-store paper, and that looked funny, too, when you put it with the other.

And then she'd figured out the exact price of the ad-only it wasn't the exact price.

I went on down the street toward film row, wondering why, since she always fouled me up, I ever bothered to listen to Elizabeth. Wondering whether I was actually as big a chump as she always said I was. I wish now that I'd kept on wondering instead of plowing on ahead. But I didn't, and I don't think it proves I wasn't smart because I didn't.

When Elizabeth and I were married there was another show in Stoneville. It wasn't much of a house-five hundred chairs, and a couple of Powers projectors that should have been in a museum, and a wildcat sound system.

But it was a show and it pulled a lot of business from us, particularly on Friday and Saturday, the horse-opera nights. Not only that, it almost doubled the price of the product we bought.

In a town of seventy-five hundred people, you hadn't ought to pay more than thirty or thirty-five bucks for the best feature out. And you don't have to if you've got the only house. Where there's more than one, well, brother, there's a situation the boys on film row love.

If you don't want to buy from them, they'll just take their product across the street. And the guy across the street will snap it up in the hopes of freezing you out and buying at his own price the next year.

The fellow that owned the other house was named Bower. He's not around any more; don't know what ever did become of him. About the time his lease came up for renewal, I went to his landlord and offered to take over, paying all operating-expenses and giving him fifty per cent of the net.

Of course he took me up. Bower couldn't afford to make a proposition like that. Neither could I.

I gave Bower a hundred and fifty dollars for his equipment, which was a good price even if he didn't think so. Motion picture equipment is worth just about as much as the spot you have it in. It's tricky stuff to move; it's made to be put in a place and left there.

Well, Bower had about the same amount of stinker product under contract that I had. Part of it he'd bought because he couldn't help himself-we had block-booking in those days-and part because it would squeeze me.

Ordinarily, if he played it at all, he'd have balanced it up with good strong shorts. But there was a lot of it he couldn't have played on a triple bill with two strong supporting features.

What I did was to take his stinkers and mine and shoot 'em into the house, one after another. And I picked out shorts that were companion pieces, if you know what I mean. Inside of two months the house wasn't grossing five dollars a day.

The landlord was-he still is, for that matter-old Andy Taylor. Andy got his start writing insurance around our neck of the woods almost fifty years ago, and now he owns about half the county in fee and has the rest under mortgage. You could hear him crying in the next county when he saw what he was up against. But there wasn't a thing he could do.

He had the choice of taking twenty-five a month or fifty per cent of nothing, so you know what he took. I left the house standing dark, just like it is now.

No one but a sucker would think of trying to open a third house under the circumstances, and he wouldn't have anything to play in it if he did. I buy all the major studio product and everything that's playable from the indies. Our house is on seven changes a week, and we actually change four or five times. The rest of the stuff we pay for and send back.

Our film bill only runs about thirty per cent more on the week than it used to, and our gross is about ninety per cent more. Of course, we've got to pay rent on the other house, and the extra express and insurance charges plus paper-advertising matter-runs into dough. But we've done all right. Plenty all right. We've got the most modern, most completely equipped small-city house in the state, and there's just one guy responsible.

Me.

I only book a month at a time. But booking with me for a month is equal to booking with the average exhibitor for three months; and the boys on the row don't exactly throw rocks at me.

I like to never have got away from the Playgrand exchange.

The minute I stepped in the door they rushed me back to the manager's office, and he just pushed his work aside and reached for the drinks.

They had some shorts in that he wanted my opinion on, so after a while we went back into the screening room, which is just like a little theater, and checked them over. They were good stuff, some of the brightest, snappiest shorts I'd seen in a longtime. Even with all I had on my mind I enjoyed them.

I've known the manager of Utopian since the days when he was on the road, and it was pretty hard to get away from there, too. And we got to talking baseball over at Colfax; and at Wolf I had to sit in on another screening and have another couple drinks.

I almost didn't book anything at Superior.

They had a complete new setup from booker to manager, and none of them knew straight up. They didn't even know who I was. I gave the booker three feature dates and five shorts, and I explained about six times that that was all I had open for the month. But he wouldn't give up. He reached over and took my date book right out of my hands.

"Why, here," he said. "We've made a mistake, haven't we? We've got an open date next Sunday."