TABLE OF CONTENTS

A BOOK OF ESCAPES AND HURRIED JOURNEYS

..................

PREFACE

..................

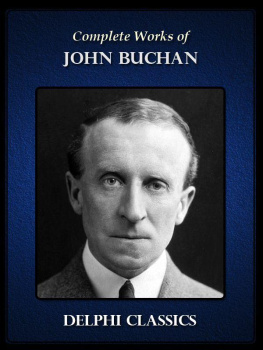

I HAVE NEVER YET SEEN an adequate definition of Romance, and I am not going to attempt one. But I take it that it means in the widest sense that which affects the mind with a sense of wonderthe surprises of life, fights against odds, weak things confounding strong, beauty and courage flowering in unlikely places. In this book we are concerned with only a little plot of a great province, the efforts of men to cover a certain space within a certain limited time under an urgent compulsion, which strains to the uttermost body and spirit.

Why is there such an eternal fascination about tales of hurried journeys? In the great romances of literature they provide many of the chief dramatic moments, and, since the theme is common to Homer and the penny reciter, it must appeal to a very ancient instinct in human nature. The truth seems to be that we live our lives under the twin categories of time and space, and that when the two come into conflict we get the great moment. Whether failure or success is the result, life is sharpened, intensified, idealized. A long journey even with the most lofty purpose may be a dull thing to read of, if it is made at leisure; but a hundred yards may be a breathless business if only a few seconds are granted to complete it. For then it becomes a sporting event, a race; and the interest which makes millions read of the Derby is the same in a grosser form as that with which we follow an expedition straining to relieve a beleaguered fort, or a man fleeing to sanctuary with the avenger behind him.

I have included escapes in my title, for the conflict of space and time is of the essence of all escapes, since the escaper is either pursued or in instant danger of pursuit. But, as a matter of fact, many escapes are slow affairs and their interest lies rather in ingenuity than in speed. Such in fiction is the escape of Dants in Monte Cristo from the dungeons of Chateau dIf, and in history the laborious tunnelling performances of some of the prisoners in the American Civil War. The escapes I have chosen are, therefore, of a special typethe hustled kind, where there has been no time to spare, and the pursuer has either been hot-foot on the trail or the fugitive has moved throughout in an atmosphere of imminent peril.

It is, of course, in the operations of war that one looks for the greater examples. The most famous hurried journeys have been made by soldiersby Alexander, Hannibal, and Julius Csar; by Marlborough in his dash to Blenheim; by Napoleon many times; by Sir John Moore in his retreat to Corunna; by a dozen commanders in the Indian Mutiny; by Stonewall Jackson and Jeb Stuart in their whirlwind rides; by the fruitless expedition to relieve Gordon. But the operations of war are a little beside my purpose. In them the movement is, as a rule, only swift when compared with the normal pace of armies, and the cumbrousness and elaboration of the military machine lessen the feeling of personal adventure. I have included only one march of an armyMontroses, because his army was such a little one, its speed so amazing and its purpose so audacious, that its swoop upon Inverlochy may be said to belong to the class of personal exploits. For a different reason I have included none of the marvellous escapes of the Great War. These are in a world of their own, and some day I may make a book of them.

I have retold the stories, which are all strictly true, using the best evidence I could find and, in the case of the older ones, often comparing a dozen authorities. For the account of Prince Charlies wanderings I have to thank my friend Professor Rait of Glasgow, the Historiographer Royal for Scotland. My aim has been to include the widest varieties of fateful and hasty journey, extending from the hundred yards or so of Lord Nithsdales walk to the Tower Gate to the 4,000 miles of Lieutenants Parer and MIntosh, from the ride of the obscure Dick King to the nights of princes, from the midsummer tragedy of Marie Antoinette to the winter comedy of Princess Clementina.

J.B.

I. THE FLIGHT TO VARENNES

..................

I

On the night of Monday, 20th June, in the year 1791, the baked streets of Paris were cooling after a day of cloudless sun. The pavements were emptying and the last hackney coaches were conveying festive citizens homewards. In the Rue de lEchelle, at the corner where it is cut by the Rue St. Honor, and where the Htel de Normandie stands to-day, a hackney carriage, of the type which was then called a glass coach, stood waiting by the kerb. It stood opposite the door of one Ronsin, a saddler, as if expecting a fare; but the windows were shuttered, and the honest Ronsin had gone to bed. On the box sat a driver in the ordinary clothes of a coachman, who while he waited took snuff with other cabbies, and with much good-humoured chaff declined invitations to drink.

The hour of eleven struck; the streets grew emptier and darker; but still the coach waited. Presently from the direction of the Tuileries came a hooded lady with two hooded children, who, at a nod from the driver, entered the coach. Then came another veiled lady attended by a servant, and then a stout male figure with a wig and a round hat, who, as he passed the sentries at the palace gate, found his shoe-buckle undone and bent to fasten it, thereby hiding his face. The glass coach was now nearly full; but still the driver waited.

The little group of people all bore famous names. On the box, in the drivers cloak, sat Count Axel Fersen, a young Swedish nobleman who had vowed his life to the service of the Queen of France. The first hooded lady, whose passport proclaimed that she was a Russian gentlewoman, one Baroness de Korff, was the Duchess de Tourzel, the governess of the royal children. The other hooded lady was no other than Madame Elizabeth, the Kings sister. One of the children was the little Princess Royal, afterwards known as the Duchess dAngoulme; the other, also dressed like a girl, was the Dauphin. The stout gentleman in the round hat was King Louis XVI. The coach in the Rue de lEchelle was awaiting the Queen.

For months the royal family had been prisoners in the Tuileries, while the Revolution marched forward in swift stages. They were prisoners in the strictest sense, for they had been forbidden even the customary Easter visit to St. Cloud. The puzzled, indolent king was no better than a cork tossed upon yeasty waters. Mirabeau was deadMirabeau who might have saved the monarchy; now the only hope was to save the royal family, for the shades were growing very dark around it. Marie Antoinette, the Queen, who, as Mirabeau had said, was the only man the King had about him, had resolved to make a dash for freedom. She would leave Paris, even France, and seek her friends beyond the borders. The National Militia and the National Guards were for the Revolution; but the army of Bouill on the eastern frontier, composed largely of German mercenaries, would do its generals orders, and Bouill was staunch for the crown. Count Fersen had organized the plan, and the young Duke de Choiseul, a nephew of the minister of Louis XV., had come to Paris to settle the details. A coach had been built for the journey, a huge erection of leather and wood, of the type then called a berline, painted yellow, upholstered in white velvet, and drawn by no less than eleven horses. It was even now standing outside the eastern gate, and Fersen was waiting with his hackney carriage to conduct the royal fugitives thither. But where was the Queen? Marie Antoinette, dressed as a maid and wearing a broad gipsy hat, had managed to pass the palace doors; but rumours had got abroad, and even as she stood there leaning on a servants arm the carriage of Lafayette dashed up to the arch, for he had been summoned by the Commandant, who represented the eyes of the National Assembly. The sight flurried her, and she and her servant took the wrong turning. They hastened towards the river, and then back, but found no waiting coach.