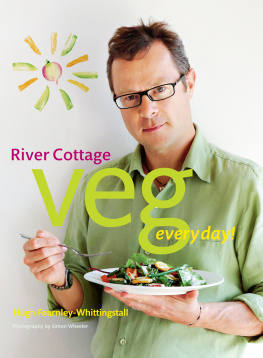

Hugh Fearlessly Eats It All

DISPATCHES FROM THE GASTRONOMIC FRONT LINE

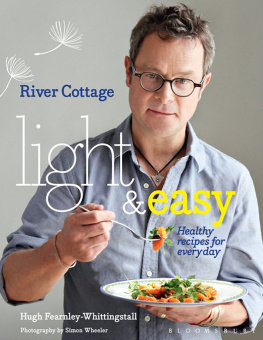

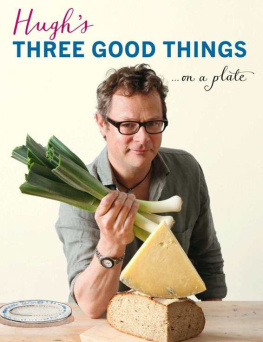

HUGH FEARNLEY-WHITTINGSTALL

First published in Great Britain 2006

Copyright 2006 by Hugh Fearnley-Whittingstall

This electronic edition published 2011 by Bloomsbury Publishing Plc

The right of Hugh Fearnley-Whittingstall to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988

All rights reserved. You may not copy, distribute, transmit, reproduce or otherwise make available this publication (or any part of it) in any form, or by any means (including without limitation electronic, digital, optical, mechanical, photocopying, printing, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of the publisher. Any person who does any unauthorised act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages.

Bloomsbury Publishing Plc, 36 Soho Square, London W1D 3QY

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN 978 1 4088 0665 4

www.bloomsbury.com/hughfearnley-whittingstall

Visit www.bloomsbury.com to find out more about our authors and their books.

You will find extracts, authors interviews, author events and you can sign up for newsletters to be the first to hear about our latest releases and special offers.

For Pots and Ivan, who dont mind if they do

First, a huge thank you to Ruth Metzstein, both for gainful past employment and for invaluable help in choosing and editing this collection. Thanks also to all of the following editors and colleagues past, present and who knows maybe future: Lisa Freedman, Aurea Carpenter, Miranda Carter, David Thomas, Shane Watson, Carron Staplehurst, Adrienne Connors, Nicola Jeal, Caroline Roux and Rebecca Seal. At Bloomsbury, thanks especially to Richard Atkinson, Natalie Hunt and Will Webb. And finally, thanks again, as ever, to my agent Antony Topping.

I am a food writer. Writing about food is what I do and have done, ever since I left the River Cafe in Hammersmith. Thats kind of where, and when, it all began.

I say left. Technically I was fired. It was August 1989, and I had been working there as a sous chef since the beginning of the year. I was having the time of my life, cooking with Rose and Ruth and Sam and Theo, learning all the time about the very best ingredients, about what good meat looks like, and what a box of good tomatoes smells like (intoxicating is the answer if they dont make you feel ever so slightly queasy, then they are not up to scratch). I was shown how to bone out and butterfly a leg of lamb; how to prepare a squid by pulling out all its milky innards and cutting off the tentacles just in front of its giant, all-seeing eyes; and how to clean a calfs brains, by holding them under a trickling cold tap, peeling off the fine sticky membrane, and running my fingers through the soft crevices to flush out little traces of congealed blood, and the odd tiny shard of fractured skull. This became my favourite job and whenever I had a hangover (which was often) I imagined performing the same cleansing ritual to my own throbbing brain.

Rumours had begun to circulate that someone from the kitchen was going to be let go. Despite being the most popular restaurant in London at the time as in, hardest at which to get a table it appeared the business was not prospering. In the restaurant trade the correlation between popularity and profit is not, as I have since had explained to me on numerous occasions, remotely straightforward. Its all about margins. These, the accountants had explained to Rose and Ruthie, would have to be increased. Since the restaurant was full every lunch and dinner, since the menu prices were already causing sharp intakes of breath among the diners, not to say lively comment in the press, and since the chef-proprietresses were not prepared to compromise on the quality of the ingredients, the obvious area for cutbacks was staff. The word got out one from the kitchen and two from front of house were for the chop.

Its hard to explain just how sure I was that the unfortunate sous chef whose release was imminent was not going to be me. It couldnt be me. I was just too thoroughly tuned in to what the River Cafe was about. I sniffed the herbs more often, and with louder enthusiasm, than any of the other chefs. I tasted the dishes I was preparing and those of the other chefs not once, but several times, arguing (as I still do) that you cant tell if a dish is right until you have eaten a whole portion of it. And when I made a pear and almond tart, or a chocolate oblivion cake, I did so with the undisguised enthusiasm of a greedy child, licking the bowl and the spoon, as my mum had always allowed me to do. At any given time the state of my apron, and my work station, was a testament to my passion. They couldnt possibly fire me. I was having far too good a time!

The fact is, Ruthie told me, as we sat on a bench by the Thames that Friday afternoon, youre the least effective member of the team and youre slowing everyone else down and were going to have to let you go . These harsh words had, I vaguely recall, been prefaced by a kindly, blow-softening preamble extolling the virtues of my enthusiasm and sense of fun, my interest in the ingredients I was cooking with, my good food instincts but none of that really registered. I was too busy being fired from a job I loved, and hadnt had the least intention of leaving, until it thoroughly suited me to do so. Too busy feeling the injustice the sheer wrongness of the decision. What? No. No! Surely I was the most effective member of the team, surely I was geeing everyone else up, surely they were going to have to let me stay

As I began to come to terms with my loss and it became increasingly clear, from the lack of phone calls begging me to return, that my former bosses were not exactly struggling to come to terms with theirs I realised I would have to make some big decisions. The looming question to which I rapidly had to find an answer was, are you going to get another job in a restaurant kitchen?

Another way of framing this was, Do you really want to be, and have you the talent, determination and discipline to be, a truly great restaurant chef? If not, and given that youve just been fired for being messy and lacking discipline from what is probably the most relaxed and un-hierarchical serious restaurant kitchen in the capital, how much point is there, really, in working in a hellhole dungeon of a kitchen, having your head dunked in the stock pot, being branded with salamanders, and being called a talentless c**t a hundred times a day by some cleaver-wielding, caffeine-addicted, egomaniac chef (mentioning no names) who will happily sacrifice your body, social life and sanity in pursuit of his third Michelin star. On balance, I thought, not much.

And so I became a food writer.

I am aware that some people are now of the opinion that I have the perfect job. And I am aware that, on all the available evidence, their opinion seems well founded. Writing and broadcasting about something I love, and consequently getting to spend my life discovering it, sampling it, growing it, producing it and consuming it, eventually elicits that embarrassed clich with which one tries to mask deep smugness with a dose of sarcastic self-effacement: Its a tough job, but someones got to do it. Ha-ha-ha-ha! Asked recently by another journalist for a one-word description of me, a good friend, after not much pause for thought, I suspect, came up with jammy!, and I can hardly disagree.