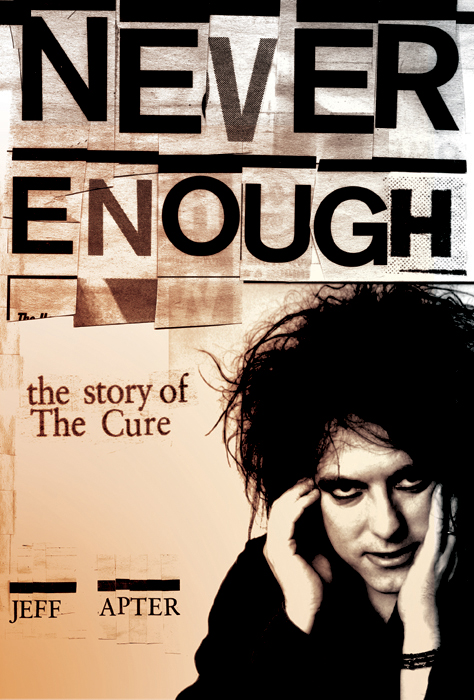

Prologue

Los Angeles Forum

July 27, 1986

Jonathan Moreland did not belong here. Surrounded by teens and 20somethings, their faces painted ghostly white, their lipstick applied haphazardly in a cosmetic tribute to Robert Smith, their new Anglo pop hero, Moreland decked out in cowboy boots and matching hat was a living, breathing anachronism. It seemed as though hed taken a wrong turn at Nashville and never quite found his way back home. The Cure definitely didnt seem like his kind of band.

But music was the last thing on Morelands mind as he shouldered his way through the crowd, finding his seat inside the LA Forum, which was filled to its 18,000 capacity. The Forum definitely wasnt a Jonathan Moreland kind of place, either. A hideous beige in colour and shaped like an upturned bowl, this venue had played host to most of the worlds biggest rocknroll acts, especially in the heady Seventies. You could see such stars as Led Zeppelin, Neil Young, The Faces and The Rolling Stones, often for less than 10 bucks, with a contact high guaranteed as part of the admission price the pot smoke that hung in the air was almost thick enough to carve. (If youre from LA, one knowledgeable local informed me about the Forum, its part of your rocknroll heritage.) It was also a venue where shows generated a huge amount of bootlegs in the pre-download world they usually came with the guarantee: Bore Em in the Forum.

Rocknroll history, however, wasnt on Jonathan Morelands mind as he found his seat. He was in an even darker mood than some of The Cures funereal dirges. Rejected by a woman called Andrea, whom he thought was the love of his life, hed arrived at the last date of the current Cure tour, their final US show for almost 12 months, with one goal: to make a lasting impression. To (literally) drive home his point, hed managed to smuggle a seven-inch hunting knife past the venues security guards. While The Cures hairdryers cooled backstage, and the band added a final flourish to their industrial strength hair gel and make-up, Moreland reached for his knife as the house lights dimmed.

The Cure may have threatened to implode almost every day of the past eight years, but 1986 had actually been a very good year. The signs were all positive: the British quintet, led by Robert Smith, mope pops very own Charlie Chaplin, had finally settled on a line-up that didnt feel the need to throttle each other after each show. That wasnt the case four years earlier, during the seemingly endless tour in support of their fourth album, the terminally bleak Pornography. During those shows, Smith and bassist Simon Gallup had even turned on the faithful, sometimes jumping headfirst into the crowd to silence those whod made clear their objections to The Cures new musical direction (and obsessions). Strange days, indeed.

But it was now 1986 and Smith seemed as content as his contrite, restless nature would allow. Hed even eased up on his boozing, while his Olympian drug-taking had now been modified to more acceptable recreational standards. At its peak, he and buddy Steve Severin, of Siouxsie & The Banshees, had once recorded an indulgence piece called Blue Sunshine while gobbling acid tabs as if they were boiled lollies. Then theyd retire to Severins London flat for all-night binges, while taking in his seemingly endless stash of gory horror videos. This became known as Smiths chemical vacation. Around the same time, Smith was also working on new Cure material and a new Banshees album, which, not surprisingly, led to the worst of his many emotionally unstable periods. But that was now in Smiths past.

And having worked their way through several US labels, in a seemingly futile effort to replicate their slowly building UK success, it seemed as though The Cures fourth and latest American home, Elektra, actually had the bands best interests at heart. Robert Smith, like so many others before and after him, had learned early on that music is a business where losing control (both creative and commercial) can be disastrous. Hed allowed the artwork of their debut album, 1979s Three Imaginary Boys, to represent the trio as a lampshade, a refrigerator and a vacuum cleaner and had been living it down ever since. But even before then, when the then Easy Cure was signed by German label Ariola/Hansa in 1977 (when the trio were still teenagers), theyd been instructed to record an assortment of rock chestnuts and greatest hits, rather than their own material, which led to one of the quickest terminations of contract this side of a Britney Spears marriage vow. Robert Smith truly had learned by experience. Now their first best-of collection, Standing On A Beach: The Singles, was on the fast track to US chart success. And MTV had taken to the eccentric Tim Pope-directed clip for Inbetween Days, which featured dancing fluoro socks, like some long-lost sibling.

Their biggest-ever Stateside tour had opened three weeks earlier, when the good ship Cure docked at the Great Woods Center for the Performing Arts in Mansfield, Massachusetts. OK, it wasnt Madison Square Garden, but the cult of The Cure which would soon reach frantic, sometimes frightening levels of adoration was clearly building. Fans rushed the stage when the band appeared, even trying to work their way past security for a personal audience with Smith, their new pop idol. This concert and those that followed wasnt so much a rock show as a gathering, a fact that wasnt lost on the Maiden Evening News. The local rag observed the serious devotion that Cure lovers felt towards their object of desire, noting how teenie-bopper girls dressed in black and white with punky hairdos risked their lives trying to get past a group of gruff security monsters to give Smith a kiss.

Over the ensuing weeks, such high-profile rags as Rolling Stone turned their spotlight on The Cure and, in particular, their seductively odd frontman. Smith was christened the male Kate Bush, the thinking teens pin-up, the security blanket of the bedsit set even a dark version of Boy George while The Cure caravan rolled on through New York, Philadelphia, Detroit, Chicago, Dallas and San Francisco, playing to increasingly larger and ever more fervent crowds. It wasnt Beatlemania, sure, but it was a clear sign that The Cure were destined for bigger things than their stop-start success so far suggested. Hell, they might even make it home without beating the stuffing out of each other.

By the night of July 27, as the band (and bandwagon) rolled into Los Angeles for their farewell headliner at the Forum, Smith whod just hacked off most of his trademark birds-nest of hair, simply for shock value was warming to both the tour and his bandmates. This was a significant development for a man whod threatened to kill off The Cure virtually every time they took a forward step. In fact, hed almost brought his contrary plan to fruition in 1982. After the punishing, depressing Pornography tour, hed shelved the band for months and hidden away in his bedroom at his parents home in Crawley, Sussex. Hed then turned his back on The Cure, defecting to the Banshees camp, craving the near-anonymity of being just another guy in the band, rather than life as the creative force and focal point of The Cure.

Smith had to be persuaded back to Cureworld by long-time manager Chris Parry, and even then only under the proviso that he could release the seemingly throwaway Lets Go To Bed. It was a song that was actually designed by Smith to either kill off the band forever or at least alienate every young mopeful whod likened The Cures gloomy moodscapes to those of Joy Division and the doomed Ian Curtis. Much to Smiths bewilderment, the very unCure-like Lets Go To Bed became an accidental hit, while its sequel, the equally disposable at least to Smiths ears The Lovecats, went even larger, becoming their biggest UK single. What was a confused 23-year-old Robert Smith to do? When he realised that The Cure were the band that refused to die, he chose simply to let it be. Now here he was in America receiving the full star treatment.