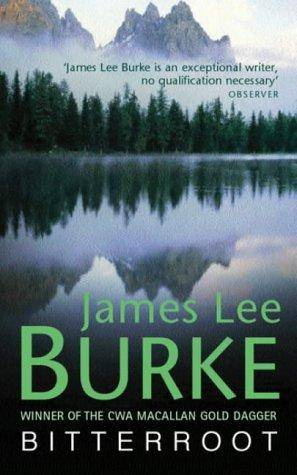

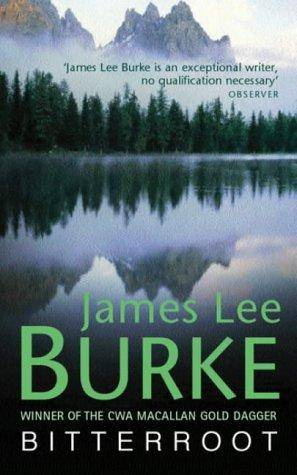

James Lee Burke

Bitterroot

The third book in the Billy Bob Holland series

ONCE AGAIN I'd like to thank my wife Pearl and our children Jim, Jr., Andree, Pamala, and Alafair for always being with me.

I'd also like to thank Father Edmond E. Bliven for his insight into the historical and theological nature of Christian baptism.

For Jack and Shelly Meyer

Doc Voss'S FOLKS were farmers of German descent, Mennonite pacifists who ran a few head of Brahman outside of Deaf Smith, Texas, and raised beans and melons and tomatoes and paid their taxes and generally went their own way. When Doc got his draft notice his senior year in high school, a lot of us thought he might apply for exemption as a conscientious objector. Instead, Doc enlisted in the Navy and became a hospital corpsman attached to the Marines.

Then he got hooked up with Force Reconnaissance and ended up a SEAL and both a helicopter and fixed-wing pilot who did extractions on the Cambodian border. In fact, Doc became one of the most decorated participants in the Vietnam War.

The night Doc returned home he burned his uniform in the backyard of his house, methodically hanging each piece from a stick over a fire that swirled out of a rusted oil drum, dissolving his Marine-issue tropicals into glowing threadworms. He joined a fundamentalist church, one even more radical in its views than his family's traditional faith. When asked to give witness, he rose in the midst of the congregation and calmly recited a story of a village incursion that made his fellow parishioners in the slat-board church house weep and tremble.

At the end of harvest season he disappeared into Mexico. We heard rumors that Doc was an addict, living in a hut on the Bay of Campeche, his mind gone, his hair and beard like a lion's mane, his body pocked with sores.

I received a grimed, pencil-written postcard from him that read: "Dear Billy Bob, Don't let the politicians or the generals get you. I swim with dolphins in the morning. The ocean is full of light and the dolphins speak to me as one of their own. At least I think they do.

"Your bud, the guy who used to be Tobin Voss."

But two years later Doc came back to us, gaunt, his face shaved, his hair cropped like a convict's, a notebook full of poems stuffed down in his duffel bag.

He worked through the summer with his father and mother, selling melons and cantaloupes and strawberries off a tailgate outside of San Antonio, then enrolled at the university in San Marcos. Before we knew it, Doc graduated and went on to Baylor and received a medical degree.

We stopped worrying about Doc, in an almost self-congratulatory way, as you do when an errant relative finally becomes what you thought he should have always been. Doc never talked about the war, except in a collection of poems he published, then in a collection of stories based on the poems, one that perhaps a famous film director stole from in producing an award-winning movie about the Vietnam War.

Doc ran a clinic in Deaf Smith and married a girl from Montana. When he lost her in a plane crash five years ago, he handled tragedy in his own life as he had handled the war. He didn't talk about it.

Nor of the fires that had never died inside him or the latent potential for violence that the gentleness in his eyes denied.

Doc's deceased WIFE had come from a ranching family in the Bitterroot Valley of western Montana. When Doc first met her on a fishing vacation nearly twenty years ago, I think he fell in love with her state almost as much as he did with her. After her death and burial on her family's ranch, he returned to Montana again and again, spending the entire summer and holiday season there, floating the Bitterroot River or cross-country skiing and climbing in the Bitterroot Mountains with pitons and ice ax. I suspected in Doc's mind his wife was still with him when he glided down the old sunlit ski trails that crisscrossed the timber above her burial place. Finally he bought a log house on the Blackfoot River. He said it was only a vacation home, but I believed Doc was slipping away from us. Perhaps true peace might eventually come into his life, I told myself.

Then, just last June, he invited me for an indefinite visit. I turned my law office over to a partner for three months and headed north with creel and fly rod in the foolish hope that somehow my own ghosts did not cross state lines.

Supposedly the word " Missoula " is from the Salish Indian language and means "the meeting of the rivers." The area is so named because it is there that both the Bitterroot and Blackfoot rivers flow into the Clark Fork of the Columbia.

The wooded hills above the Blackfoot River where Doc had bought his home were still dark at 7 A.M., the moon like a sliver of crusted ice above a steep-sided rock canyon that rose to a plateau covered with ponderosa. The river seemed to glow with a black, metallic light, and steam boiled out of the falls in the channels and off the boulders that were exposed in the current.

I picked up my fly rod and net and canvas creel from the porch of Doc's house and walked down the path toward the riverbank. The air smelled of the water's coldness and the humus back in the darkness of the woods and the deer and elk dung that had dried on the pebbled banks of the river. I watched Doc Voss squat on his haunches in front of a driftwood fire and stir the strips of ham in a skillet with a fork, squinting his eyes against the smoke, his upper body warmed only by a fly vest, his shoulders braided with sinew. Then the sun broke through the tree trunks on the ridge and lighted the meadows and woods and cliffs around us with a pinkness that made us involuntarily look up into the vastness of the Montana sky, as though the stars had been unfairly stolen from us.

Doc handed me a tin plate filled with eggs and ham and chunks of bread he had cut on a rock and browned in the ham's fat. He sat down beside me on a grassy, soft spot and leaned back against a boulder and drank from a collapsible stainless steel coffee cup and watched his daughter standing thigh-deep in the river, without waders, indifferent to the cold, fishing in a pool that swirled behind a rotted cottonwood. He took a tiny salt and pepper shaker out of his rucksack, then removed a holstered.44 Magnum revolver from the sack and set it on top of some ferns, the wide belt and heavy, square brass buckle and leather-snugged cartridges wrapped across the cherrywood grips.

"Fine-looking gun," I said.

"Thank you," he replied.

"Fixing to shoot the rainbow that won't jump in your creel?" I said.

"Cougars come down through the trees at night. They get into the cat bowls and such."

"It's not night," I said.

He grinned at nothing and looked in his daughter's direction. She was a junior in high school, her blond hair cropped short on the back of her neck, her denim shirt tight across her waist when she lifted her rod above her head and pulled her line dripping from under the river's surface and false-cast the dry fly on the tippet in a figure eight.

Doc kept touching his jawbone with his thumb, as though he had an impacted wisdom tooth.

"What are you studying on?" I asked.

"Me?"

"No. The rock you're leaning against."

"The country's going to hell," he said.

"People have been saying that for two hundred years."

"You've been here eleven hours and you've got it all figured out. I wish I had them kind of smarts," he replied.

He left his food uneaten and walked upstream with his fly rod, his long, ash-blond hair blowing in the wind, his shoulders stooped like an ancient hunter's.

Next page