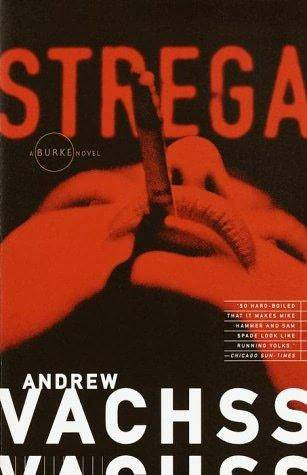

The second book in the Burke series

For Doc, who heard it all while he was down here.

For Mary Lou, who can hear it all now.

For Sam, who finally gave up his part-time job.

And for Bobby, who died trying.

Different paths to the same door.

To Ira J. Hechler, the master-builder content to allow others to engrave their names on the cornerstones of his achievements, I acknowledge my gratitude and proclaim my respect.

IT STARTED with a kid.

The redhead walked slowly up the bridle path, one foot deliberately in front of the other, looking straight ahead. She was dressed in a heavy sweatsuit and carrying some kind of gym bag in her hand. Her flaming hair was tied behind her with a wide yellow ribbon, just as it was supposed to be.

Forest Park runs all through Queens County, just a dozen miles outside the city. It's a long narrow piece of greenery, stretching from Forest Hills, where Geraldine Ferraro sells Pepsi, all the way to Richmond Hill, where some people sell coke. At six in the morning, the park was nearly deserted, but it would fill up soon enough. Yuppies working up an appetite for breakfast yogurt, jogging through the forest, dreaming of things you can buy from catalogues.

I was deep into the thick brush along the path, safely hidden behind a window screen. It had taken a couple of hours to weave the small branches through the mesh, but it was worth it-I was invisible. It was like being back in Biafra during the war, except that only branches were over my head-no planes.

The redhead stopped on the path, just across from me, about twenty feet away. Moving as if all her joints were stiff in the early-spring cold, she pulled the sweatshirt over her head, untied the pants, and let them fall to the ground. Now she was dressed in just a tight tank top and a skimpy pair of silky white shorts. "No panties, no bra," the freak had told her on the phone. "I want to see everything you got bounce around, you got it?" She was supposed to do three laps around the bridle path, and then it would be over.

I had never spoken to the woman. I got the story from an old man I did time with years ago. Julio called me at Mama Wong's restaurant and left a message to meet at a gas station he owns over in Brooklyn. "Tell him to bring the dog," he told Mama.

Julio loves my dog. Her name is Pansy and she's a Neapolitan mastiff-about 140 pounds of vicious muscle and dumb as a brick. If her entire brain was high-quality cocaine, it wouldn't retail for enough cash to buy a decent meal. But she knows how to do her work, which is more than you can say for a lot of fools who went to Harvard.

Back when I did my last long stretch, the prison yard was divided into little courts-every clique had one, the Italians, the blacks, the Latins. But it didn't just break down to race-bank robbers hung out together, con men had their own spot, the iron-freaks didn't mix with the basketball junkieslike that. If you stepped on a stranger's court, you did it the same way you'd come into his cell without an invite-with a shank in your hand. People who don't have much get ugly about giving up the little they have left.

Julio's court was the biggest one on the yard. He had tomato plants growing there, and even some decent chairs and a table someone made for him in the wood shop. He used to make book at the same stand every day-cons are all gamblers, otherwise they'd work for a living. Every morning he'd be out there on his court, sitting on a box near his tomato plants, surrounded by muscle. He was an old man even then, and he carried a lot of respect. One day I was talking to him about dogs, and he started in about Neapolitans.

"When I was a young boy, in my country, they had a fucking statue of that dog right in the middle of the village," he told me. "Neapolitan mastiffs, Burke-the same dogs what came over the Alps with Hannibal. I get out of this place, the first thing I do is get one of those dogs."

He was a better salesman than he was a buyer-Julio never got a Neapolitan, but I did. I bought Pansy when she was a puppy and now she's a full-grown monster. Every time Julio sees her, tears come into his eyes. I guess the idea of a cold-blooded killer who can never inform on the contractor makes him sentimental.

I drove my Plymouth into the gas station, got the eye from the attendant, and pulled into the garage. The old man came out of the darkness and Pansy growled-it sounded like a diesel truck downshifting. As soon as she recognized Julio's voice her ears went back just a fraction of an inch, but she was still ready to bite.

"Pansy! Mother of God, Burke-she's the size of a fucking house! What a beauty!"

Pansy purred under the praise, knowing there were better things coming. Sure enough, the old man reached in a coat pocket and came out with a slab of milk-white cheese and held it out to her.

"So, baby-you like what Uncle Julio has for you, huh?"

Before Julio could get close enough, I snapped "Speak!" at Pansy. She let the old man pat her massive head as the cheese quickly disappeared. Julio thought "Speak!" meant she should make noises-actually, it was the word I taught her that meant it was okay to take food. To Julio, it looked like a dog doing a trick. The key to survival in this world is to have people think you're doing tricks for them. Nobody was going to poison my dog.

Pansy growled again, this time in anticipation. "Pansy, jump!" I barked at her, and she lay down in the back seat without another sound.

I got out of the car and lit a cigarette-Julio wouldn't call me out to Brooklyn just to give Pansy some cheese.

"Burke, an old friend of mine comes to me last week. He says this freak is doing something to his daughter, making her crazy-scared all the time. And he don't know what to do. He tries to talk to her and she won't tell him what's wrong. And the daughter-she's married to a citizen, you know? Nice guy, treats her good and everything. He earns good, but he's not one of us. We can't bring him in on this."

I just watched the old man. He was so shook he was trembling. Julio had killed two shooters in a gunfight just before he went to prison and he was standup all the way. This had to be bad. I let him talk, saying nothing.

"So I talk to her-Gina. She won't tell me neither, but I just sit and we talk about things like when she was a little girl and I used to let her drink some of my espresso when she came into the club with her father-stuff like that. And then I notice that she won't let this kid of hers out of her sight. The little girl, she wants to go out in the yard and play and Gina says no. And it's a beautiful day out, you understand? They got a fence around the house, she can watch the kid from the kitchen-but she's not letting her out of her sight. So then I ask her, Is it something about the kid?

"And then she starts to cry, right in front of me and the kid too. She shows me this brown envelope that came in the mail for her. It's got all newspaper stories of kids that got killed by drunk drivers, kids that got snatched, missing kidsall that kind of shit."

"So what?" I ask her. What's this got to do with your kid? And she tells me that this stuff comes in the mail for weeks, okay? And then this animale calls her on the phone. He tells her that he did a couple of these kids himself, you understand what I'm saying?-he snatches the kids himself and all. And her kid is going to be next if she don't do what he wants.

"So she figures he wants money, right? She knows that could be taken care of. But he don't want money, Burke. He wants her to take off her clothes for him while she's on the phone, the freak. He tells her to take the clothes off and say what she's doing into the phone."

Next page