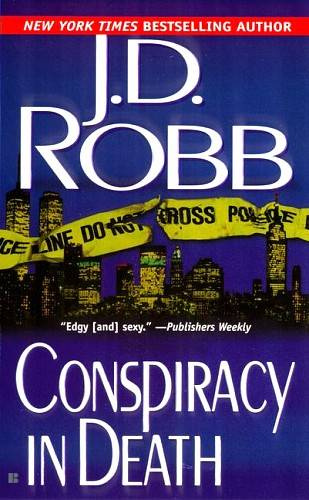

J. D. Robb

Conspiracy in Death

Eve Dallas and husband Roarke

In my hands is power. The power to heal or to destroy. To grant life or to cause death. I revere this gift, have honed it over time to an art as magnificent and awesome as any painting in the Louvre.

I am art, I am science. In all the ways that matter, I am God.

God must be ruthless and far-sighted. God studies his creations and selects. The best of these creations must be cherished, protected, sustained. Greatness rewards perfection.

Yet even the flawed have purpose.

A wise God experiments, considers, uses what comes into His hands and forges wonders. Yes, often without mercy, often with a violence the ordinary condemn.

We who hold power cannot be distracted by the condemnations of the ordinary, by the petty and pitiful laws of simple men. They are blind, their minds are closed with fear fear of pain, fear of death. They are too limited to comprehend that death can be conquered.

I have nearly done so.

If my work was discovered, they, with their foolish laws and attitudes, would damn me.

When my work is complete, they will worship me.

For some, death wasn't the enemy. Life was a much less merciful opponent. For the ghosts who drifted through the nights like shadows, the funky-junkies with their pale pink eyes, the chemi-heads with their jittery hands, life was simply a mindless trip that circled from one fix to the next with the arcs between a misery.

The trip itself was most often full of pain and despair, and occasionally terror.

For the poor and displaced in the bowels of New York City in the icy dawn of 2059, the pain, the despair, the terror were constant companions. For the mental defectives and physically flawed who slipped through society's cracks, the city was simply another kind of prison.

There were social programs, of course. It was, after all, an enlightened time. So the politicians claimed, with the Liberal Party shouting for elaborate new shelters, educational and medical facilities, training and rehabilitation centers, without actually detailing a plan for how such programs would be funded. The Conservative Party gleefully cut the budgets of what programs were already in place, then made staunch speeches on the quality of life and family.

Still, shelters were available for those who qualified and could stomach the thin and sticky hand of charity. Training and assistance programs were offered for those who could keep sane long enough to wind their way through the endless tangled miles of bureaucratic red tape that all too often strangled the intended recipients before saving them.

And as always, children went hungry, women sold their bodies, and men killed for a handful of credits.

However enlightened the times, human nature remained as predictable as death.

For the sidewalk sleepers, January in New York brought vicious nights with a cold that could rarely be fought back with a bottle of brew or a few scavenged illegals. Some gave in and shuffled into the shelters to snore on lumpy cots under thin blankets or eat the watery soup and tasteless soy loaves served by bright-eyed sociology students. Others held out, too lost or too stubborn to give up their square of turf.

And many slipped from life to death during those bitter nights.

The city had killed them, but no one called it homicide.

***

As Lieutenant Eve Dallas drove downtown in the shivering dawn, she tapped her fingers restlessly on the wheel. The routine death of a sidewalk sleeper in the Bowery shouldn't have been her problem. It was a matter for what the department often called Homicide-Lite the stiff scoopers who patrolled known areas of homeless villages to separate living from dead and take the used-up bodies to the morgue for examination, identification, and disposal.

It was a mundane and ugly little job most usually done by those who either still had hopes of joining the more elite Homicide unit or those who had given up on such a miracle. Homicide was called to the scene only when the death was clearly suspicious or violent.

And, Eve thought, if she hadn't been on top of the rotation for such calls on this miserable morning, she'd still be in her nice warm bed with her nice warm husband.

"Probably some jittery rookie hoping for a serial killer," she muttered.

Beside her, Peabody yawned hugely. "I'm really just extra weight here." From under her ruler-straight dark bangs, she sent Eve a hopeful look. "You could just drop me off at the closest transpo stop and I can be back home and in bed in ten minutes."

"If I suffer, you suffer."

"That makes me feel so loved, Dallas."

Eve snorted and shot Peabody a grin. No one, she thought, was sturdier, no one was more dependable, than her aide. Even with the rudely early call, Peabody was pressed and polished in her winter-weight uniform, the buttons gleaming, the hard black cop shoes shined. In her square face framed by her dark bowl-cut hair, her eyes might have been a little sleepy, but they would see what Eve needed her to see.

"Didn't you have some big deal last night?" Peabody asked her.

"Yeah, in East Washington. Roarke had this dinner / dance thing for some fancy charity. Save the moles or something. Enough food to feed every sidewalk sleeper on the Lower East Side for a year."

"Gee, that's tough on you. I bet you had to get all dressed up in some beautiful gown, shuttle down on Roarke's private transpo, and choke down champagne."

Eve only lifted a brow at Peabody 's dust-dry tone. "Yeah, that's about it." They both knew the glamorous side of Eve's life since Roarke had come into it was both a puzzlement and a frustration to her. "And then I had to dance with Roarke. A lot."

"Was he wearing a tux?" Peabody had seen Roarke in a tux. The image of it was etched in her mind like acid on glass.

"Oh yeah." Until, Eve mused, they'd gotten home and she'd ripped it off of him. He looked every bit as good out of a tux as in one.

"Man." Peabody closed her eyes, indulged herself with a visualization technique she'd learned at her Free-Ager parents' knees. "Man," she repeated.

"You know, a lot of women would get pissed off at having their husband star in their aide's purient little fantasies."

"But you're bigger than that, Lieutenant. I like that about you."

Eve grunted, rolled her stiff shoulders. It was her own fault that lust had gotten the better of her and she'd only managed three hours of sleep. Duty was duty, and she was on it.

Now she scanned the crumbling buildings, the littered streets. The scars, the warts, the tumors that sliced or bulged over concrete and steel.

Steam whooshed up from a grate, shot out from the busy half-life of movement and commerce under the streets. Driving through it was like slicing through fog on a dirty river.

Her home, since Roarke, was a world apart from this. She lived with polished wood, gleaming crystal, the scent of candles and hothouse flowers. Of wealth.

But she knew what it was to come from such places as this. Knew how much the same they were city by city in smells, in routines, in hopelessness.

The streets were nearly empty. Few of the residents of this nasty little sector ventured out early. The dealers and street whores would have finished the night's business, would have crawled back into their flops before sunrise. Merchants brave enough to run the shops and stores had yet to uncode their riot bars from the doors and windows. Glide-cart vendors desperate enough to hawk this turf would carry hand zappers and work in pairs.

She spotted the black and white patrol car, scowled at the half-assed job the officers on scene had done with securing the area.

Next page