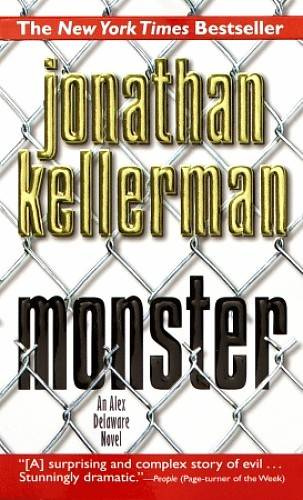

Jonathan Kellerman

Monster

Book 13 in the Alex Delaware series, 1999

TO THE MEMORY

of

KENNETH MILLAR

The giant knew Richard Nixon.

Towering, yellow-haired, grizzled, a listing mountain in khaki twill, he limped closer, and Milo tightened up. I looked to Frank Dollard for a cue. Dollard appeared untroubled, meaty arms at his sides, mouth serene under the tobaccoed gray mustache. His eyes were slits, but they'd been that way at the main gate.

The giant belched out a bass laugh and brushed greasy hair away from his eyes. His beard was a corn-colored ruin. I could smell him now, vinegarish, hormonally charged. He had to be six-eight, three hundred. The shadow he threw on the dirt was ash-colored, amoebic, broad enough to shade us.

He took another lurching step, and this time Frank Dollard's right arm shot out.

The huge man didn't seem to notice, just stood there with Dollard's limb flung across his waist. Maybe a dozen other men in khaki were out on the yard, most of them standing still, a few others pacing, rocking, faces pressed against the chain link. No groups that I could see; everyone to himself. Above them, the sky was an untrammeled blue, clouds broiled away by a vengeful sun. I was cooking in my suit.

The giant's face was dry. He sighed, dropped his shoulders, and Dollard lowered his arm. The giant made a finger gun, pointed it at us, and laughed. His eyes were dark brown, pinched at the corners, the whites too sallow for health.

"Secret service." He thumped his chest. "Victoria's Secret service in the closet underwear undercover always lookin' out for the guy good old Nixon RMN Rimmin, always rimmin wanting to be rimmed he liked to talk the walk cuttin outta the White House night house doing the party thing all hours with Kurt Vonnegut J.D. Salinger the Glass family anyone who didn't mind the politics heat of the kitchen I wrote Cat's Cradle sold it to Vonnegut for ten bucks Billy Bathgate typed the manuscript one time he walked out the front door got all the way to Las Vegas big hassle with the Hell's Angels over some dollar slots Vonnegut wanting to change the national debt Rimmin agreed the Angels got pissed we had to pull him out of it me and Kurt Vonnegut Salinger wasn't there Doctorow was sewing the Cat's Cradle they were bad cats, woulda assassinated him any day of the week leeway the oswald harvey."

He bent and lifted his left trouser leg. Below the knee was bone sheathed with glossy white scar tissue, most of the calf meat ripped away. An organic peg leg.

"Got shot protecting old Rimmin," he said, letting go of the fabric. "He died anyway poor Richard no almanac know what happened rimmed too hard I couldn't stop it."

"Chet," said Dollard, stretching to pat the giant's shoulder.

The giant shuddered. Little cherries of muscle rolled along Mile's jawline. His hand was where his gun would have been if he hadn't checked it at the gate.

Dollard said, "Gonna make it to the TV room today,

Chet?"

The giant swayed a bit. "Ahh"

"I think you should make it to the TV room, Chet. There's gonna be a movie on democracy. We're gonna sing 'The Star-Spangled Banner,' could use someone with a good voice."

"Yeah, Pavarotti," said the giant, suddenly cheerful. "He and Domingo were at Caesars Palace they didn't like the way it worked out Rimmin not doing his voice exercises lee lee lee lo lo lo no egg yolk to smooth the trachea it pissed Pavarotti off he didn't want to run for public office."

"Yeah, sure," said Dollard. He winked at Milo and me.

The giant had turned his back on all three of us and was staring down on the bare tan table of the yard. A short, thick, dark-haired man had pulled down his pants and was urinating in the dirt, setting off a tiny dust storm. None of the other men in khaki seemed to notice. The giant's face had gone stony.

"Wet," he said.

"Don't worry about it, Chet," Dollard said softly. "You know Sharbno and his bladder."

The giant didn't answer, but Dollard must have transmitted a message, because two other psych techs came jogging over from a far corner. One black, one white, just as muscular as Dollard but a lot younger, wearing the same uniform of short-sleeved sport shirt, jeans, and sneakers. Photo badges clipped to the collar. The heat and the run had turned the techs' faces wet. Mile's sport coat had soaked through at the armpits, but the giant hadn't let loose a drop of sweat.

His face tightened some more as he watched the urinating man shake himself off, then duck-walk across the yard, pants still puddled around his ankles.

"Wet."

"We'll handle it, Chet," soothed Dollard.

The black tech said, "I'll go get those trousers up."

He sauntered toward Sharbno. The white tech stayed with Chet. Dollard gave Chet another pat and we moved on.

Ten yards later, I looked back. Both techs were flanking Chet. The giant's posture had changed-shoulders higher, head craning as he continued to stare at the space vacated by Sharbno.

Milo said, "Guy that size, how can you control him?"

"We don't control him," said Dollard. "Clozapine does. Last month his dosage got upped after he beat the crap out of another patient. Broke about a dozen bones."

"Maybe he needs even more," said Milo.

"Why?"

"He doesn't exactly sound coherent."

Dollard chuckled. "Coherent." He glanced at me. "Know what his daily dosage is, Doctor? Fourteen hundred milligrams. Even with his body weight, that's pretty thorough, wouldn't you say?"

"Maximum's usually around nine hundred," I told Milo. "Lots of people do well on a third of that."

Dollard said, "He was on eleven migs when he broke the other inmate's face." Dollard's chest puffed a bit. "We exceed maximum recommendations all the time; the psychiatrists tell us it's no problem." He shrugged. "Maybe Chet'll get even more. If he does something else bad."

We covered more ground, passing more inmates. Un-trimmed hair, slack mouths, empty eyes, stained uniforms. None of the iron-pumper bulk you see in prisons. These torsos were soft, warped, deflated. I felt eyes on the back of my head, glanced to the side, and saw a man with haunted-prophet eyes and a chestful of black beard staring at me. Above the facial pelt, his cheeks were sunken and sooty. Our eyes engaged. He came toward me, arms rigid, neck bobbing. He opened his mouth. No teeth.

He didn't know me but his eyes were rich with hatred. My hands fisted. I walked faster. Dollard noticed and cocked his head. The bearded man stopped abruptly, stood there hi the full sun, planted like a shrub. The red exit sign on the far gate was five hundred feet away. Dollard's key ring jangled. No other techs in sight. We kept walking. Beautiful sky, but no birds. A machine began grinding something.

I said, "Chefs ramblings. There seems to be some intelligence there."

"What, 'cause he talks about books?" said Dollard. "I think before he went nuts he was in college somewhere. I think his family was educated."

"What got him in here?" said Milo, glancing back. "Same as all of them." Dollard scratched his mustache and kept his pace steady. The yard was vast. We were halfway across now, passing more dead eyes, frozen faces, wild looks that set up the small hairs on the back of my neck.

"Don't wear khaki or brown," Milo had said. "The inmates wear that, we don't want you stuck in there-though that would be interesting, wouldn't it? Shrink trying to convince them he's not crazy?"

"Same as all of them?" I said.

"Incompetent to stand trial," said Dollard. "Your basic 1026."

Next page