THIS IS A BORZOI BOOK

PUBLISHED BY ALFRED A. KNOPF

Copyright 2012 by the John H. Updike Literary Trust

All rights reserved. Published in the United States of America by Alfred A. Knopf, a division of Random House, Inc., New York, and in Canada by Random House of Canada, Ltd., Toronto. www.aaknopf.com

The texts of three of these pieces, Pictures and Words, A Case of Monumentality, and Big, Bright, and Bendayed, are reprinted from More Matter, John Updikes nonfiction collection published by Alfred A. Knopf in 1999.

Excerpts from The Clarity of Things were published in The New York Review of Books and Humanities magazine. The full text of this lecture made reference to sixty-four images projected onscreen while the author spoke; it has been slightly abridged by Christopher Carduff for its appearance here.

The remaining pieces were published, in somewhat different form and sometimes under different titles, in The New York Review of Books or The New Republic. These pieces were revised by the author for eventual book publication and deposited at Houghton Library, Harvard University, in December 2008, the month before his death. They are printed here in much the form that John Updike left them, and under his preferred titles.

A list of illustration credits begins on and constitutes an extension of this copyright notice.

Knopf, Borzoi Books, and the colophon are registered trademarks

of Random House, Inc.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Updike, John.

Always looking: essays on art/by John Updike; edited by Christopher Carduff.

p. cm.

Includes index.

eISBN: 978-0-307-96183-9

1. ArtPsychology. I. Title.

N71.U63 2012

700dc23

2012005986

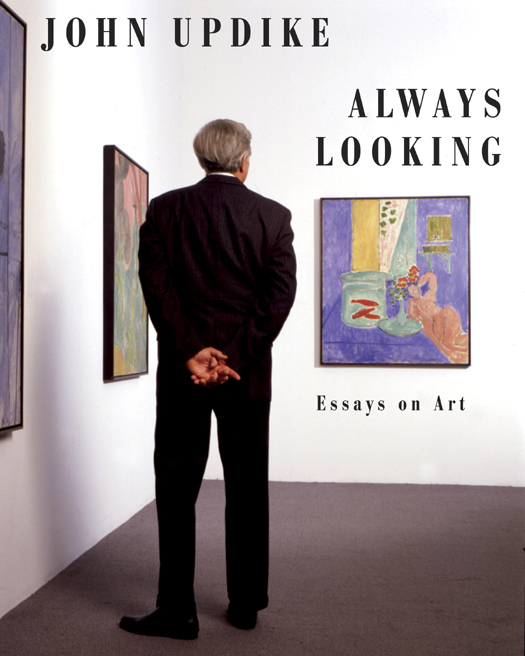

Cover image: John Updike, in 1989, looking at three paintings by Henri Matisse in the Florence May Schoenborn Gallery, The Museum of Modern Art, New York (from left to right: View of Notre Dame, 1914; Moroccan Garden, 1912; Goldfish and Sculpture, 1912). Photograph 2012 by Benno Friedman

Cover design by Chip Kidd

v3.1

The question is not what you look at

but how you look & whether you see.

H ENRY D AVID T HOREAU ,

Journal, August 5, 1851

Whats this?

Whats what?

Why, look.

J OHN U PDIKE , The Poorhouse Fair

Contents

Editors Note

Always Looking was conceived by Judith Jones of Alfred A. Knopf as a posthumous companion to John Updikes previous collections of art writings, Just Looking (1989) and Still Looking (2005). Martha Updike, Johns wife and literary executor, invited me to put together the book, which I edited in tandem with Higher Gossip, a more various collection of Updikes essays and criticism published by Knopf in 2011. Thank you, Judith and Martha, for sponsoring this final set of illustrated gallery tours, which Ive arranged as a highly selective survey of the last two hundred years of Western art, a master class in appreciation conducted from an unabashedly American perspective.

Of the thirteen exhibition reviews gathered here, ten first appeared in The New York Review of Books between 1990 and 2007. The reviews of Monet, Mir, and Magritte appeared in The New Republic between 1990 and 1993. Pictures and Words was published, as A Bookish Boy, in Life, October 1990. A Case of Monumentality was written, at the invitation of Edward Hirsch, for Transforming Vision (Bulfinch Press, 1994), a volume of essays and poems inspired by works in the collection of the Art Institute of Chicago. Updike delivered The Clarity of Things, the thirty-seventh annual Jefferson Lecture in the Humanities, at the Warner Theatre, in Washington, D.C., on May 22, 2008. Excerpts were published in The New York Review of Books and in Humanities, the magazine of the National Endowment for the Humanities.

Many thanks to my collaborators at Knopf, Peter A. Andersen, Deborah Garrison, Ken Schneider, and Caroline Zancan. I am deeply indebted to Sarah Almond, who, in securing rights to reproduce the illustrations for this volume, was less a permissions editor than a full partner in bookmaking.

Christopher Carduff

November 2011

L INDA G RACE H OYER

Preface: Pictures and Words

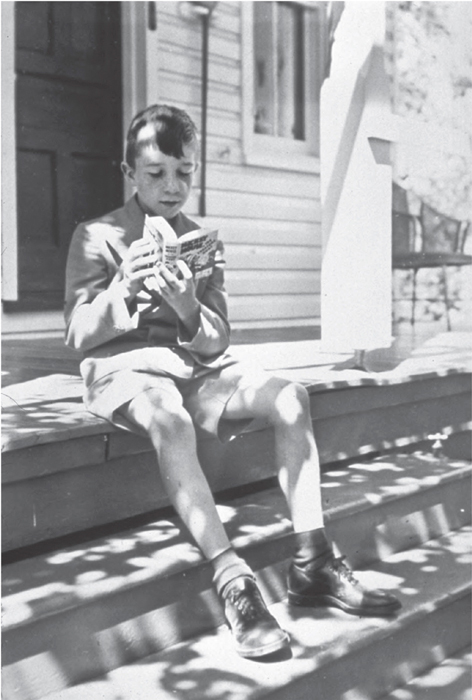

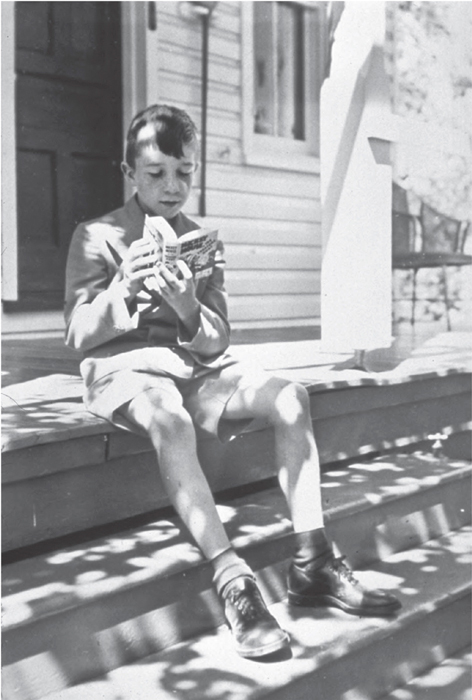

M Y MOTHER took this photograph, and dated it precisely on the back: September 21, 1941. I was, therefore, nine years, six months, and three days old. Consulting the perpetual calendar, I find that the date fell, as I suspected, on a Sunday; my little suit coat, my solid laced shoes, and a sabbath gleam in the dappled sunshine suggest a day apart. No amount of peering, even with a magnifying glass, at the photograph revives in me any memory-sensation of the moment that has been preserved, but the site is very familiar. It was one of my favorite places in the world: the side porch of the house at 117 Philadelphia Avenue, in Shillington, Pennsylvania. The house belonged to my maternal grandparents; due to the exigencies of the Depression my parents and I lived there as well. On this long side porch, half of whose length stretches out of sight to my right, I would play by myself or with otherssetting up grocery stores out of orange crates and crayoned paper fruit, making cozy houses out of overturned wicker porch furniture. A grape arbor extended outward from the porch roof, throwing its dazzling dapple down upon the steps and a brick patio where ants busily came and went between the cracks. The grapevines tendrils curled with such intricacy that I imagined they would spell the entire alphabet if I looked hard enough.

The door behind me leads into our kitchen, with its linoleum floor and wooden icebox and soapy-smelling stone sink. The kitchen smelled of vanilla, cinnamon, and shredded coconut in its glass-fronted cabinets, and of the oilcloth on the little table where we ate, I seated at a corner that prodded me in the stomach. On those days when my mother and grandmother canned, putting up peaches and pears and tomatoes in Mason jars, there was a majestic amount of steam in the kitchen, and a surplus of those fascinating little sealing rings of red rubber. These rings, and clothespins, and spools depleted of thread were common household items in that homely pre-war world, and thriftily became toys.

The broom rack is a period detail, and another broom seems to peek in at the left; sweeping was a constant rite of summer, as was fly-swatting, with its similarly shaped implement. At the end of the porch, against the radiant foliage of our back yard, sits a wire lawn-chair that had a curious destiny. When we moved, in 1945, from this house to a smaller house in the country, the wire chair, a greenish blue in color, somehow came indoors, and joined our living-room furniture. A cushion did not appreciably disguise or soften its metal mesh. Its springy seat rebounded into convexity, when you stood up, with an audible snap.

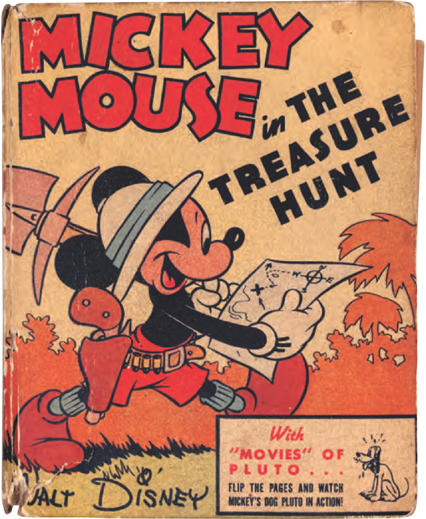

W ALT D ISNEY P RODUCTIONS