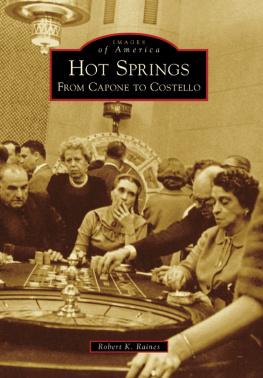

Hot Springs

Stephen Hunter

Part One

Wet Heat

Chapter

Earl's daddy was a sharp-dressed man.

Each morning he shaved carefully with a well-stropped razor, buttoned a clean, crackly starched white shirt, tied a black string tie in a bow knot. Then he pulled up his suspenders and put on his black suit coat--he owned seven Sunday suits, and he wore one each day of his adult life no matter the weather, all of them black, heavy wool from the Sears, Roebuck catalogue--and slipped a lead-shot sap into his back pocket, buckled on his Colt Peacemaker and his badge, slipped his Jesus gun inside the cuff of his left wrist, adjusted his large black Stetson, and went to work sheriffing Polk County, Arkansas.

But at this particular moment Earl remembered the ties. His father took pride in his ties, tying them perfectly, so that the knot was square, the bows symmetrical and the two ends equal in length. "Always look your best," he'd say, more than once, with the sternness that expressed his place in the world. "Do your best, look your best, be your best. Never let up. Never let go. Live by the Book. That's what the Lord wants. That's what you must give."

So one of the useless things Earl knew too much about--how to clear the jam on a Browning A-3 when it choked with volcanic dust and the Japs were hosing the position down would be another--was the proper tying of a bow tie.

And the bow tie he saw before him, at the throat of a dapper little man in a double-breasted cream-colored suit, was perfectly tied. It was clearly tied by a man who loved clothes and knew clothes and took pleasure in clothes. His suit fitted him well and there was no gap between his collar and the pink flesh of his neck nor between his starched white shirt and the lapel and collar of his cream jacket. He was a peppy, friendly little man, with small pink hands and a down - homey way to him that Earl knew well from his boyhood: it was a farmer's way, a barber's way, a druggist's way, maybe the feed store manager's way, friendly yet disciplined, open so far and not any farther.

"You know," Harry Truman said to him, as Earl stared uncertainly not into the man's powerful eyes behind his rimless glasses, but at the perfect knot of his bow tie, and the perfect proportioning of the twin loops at either end of it, and the one unlooped flap of fabric, in a heavy silk brocade, burgundy, with small blue dots across it, "I've said this many a time, and by God I will say it again. I would rather have won this award than hold the high office I now hold. You boys made us so proud with what you did. You were our best and you never, ever let us down, by God. The country will owe you as long as it exists."

Earl could think of nothing to say, and hadn't been briefed on this. Remarks, in any case, were not a strong point of his. On top of that, he was more than slightly drunk, with a good third of a pint of Boone County bourbon spread throughout his system, giving him a slightly blurred perspective on the events at which he was the center. He fought a wobble that was clearly whiskey-based, swallowed, and tried to will himself to remain ramrodded at attention. No one would notice how sloshed he was if he just kept his mouth closed and his whiskey breath sealed off. His head ached. His wounds ached. He had a stupid feeling that he might grin.

"Yes, sir, First Sergeant Swagger," said the president, "you are the best this country ever brought forth." The president seemed to blink back a genuine tear. Then he removed a golden star from a jeweler's box held by a lieutenant colonel, stepped forward and as he did so unfurled the star's garland of ribbon. Since he was smallish and Earl, at six one, was largish, he had to stretch almost to tippy-toes to loop the blue about Earl's bull neck.

The Medal of Honor dangled on the front of Earl's dress blue tunic, suspended on its ribbon next to the ribbons of war displayed across his left breast, five Battle Stars, his Navy Cross, his Unit Citations and his Good Conduct Medal. Three service stripes dandied up his lower sleeves. A flashbulb popped, its effect somewhat confusing Earl, making him think ever so briefly of the Nambu tracers, which were white-blue unlike our red tracers.

A Marine captain solemnized the moment by reading the citation: "For gallantry above and beyond the call of duty, First Sergeant Earl Lee Swagger, Able Company, First Battalion, Twenty-eighth Marines, Fifth Marine Division, is awarded the Medal of Honor for actions on Iwo Jima, D plus three, at Charlie-Dog Ridge, February 22, 1945."

Behind the president Earl could see Howlin' Mad Smith and Harry Schmidt, the two Marine generals who had commanded the boys at Iwo, and next to them James Forrestal, secretary of the navy, and next to him Earl's own pretty if wan wife, Erla June, in a flowered dress, beautiful as ever, but slightly overwhelmed by all this. It wasn't the greatness of the men around her that scared her, it was what she saw still in her husband's heart.

The president seized his hand and pumped it and a polite smattering of applause arose in the Map Room, as it was called, though no maps were to be seen, but only a lot of old furniture, as in his daddy's house. The applause seemed to play off the walls and paintings and museum like hugeness of the place. It was July 30, 1946. The war was over almost a year. Earl was no longer a Marine. His knee hardly worked at all, and his left wrist ached all the time, both of which had been struck by bullets. He still had close to thirty pieces of metal in his body. He had a pucker like a mortar crater on his ass--the 'Canal. He had another pucker in his chest, just above his left nipple-- Tarawa, the long walk in through the surf, the Japs shooting the whole way. He worked in the sawmill outside Fort Smith as a section foreman. Sooner or later he would lose a hand or an arm. Everyone did.

"So what's next for you, First Sergeant?" asked the president. "Staying in the Corps? I hope so."

"No sir. Hit too many times. My left arm don't work so good."

"Damn, hate to lose a good man like you. Anyhow, there's plenty of room for you. This country's going to take off, you just watch. Just like the man said, You ain't seen nothing yet, no sir and by God. Now we enter our greatness and I know you'll be there for it. You fought hard enough."

"Yes sir," said Earl, too polite to disagree with a man he admired so fervently, the man who'd fried the Jap cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki and saved a hundred thousand American boys in the process.

But disagree he did. He couldn't go back to school on this thing they called the GI Bill. He just couldn't. He could have no job selling or convincing. He could not teach because the young were so stupid and he had no patience, not anymore. He couldn't work for a man who hadn't been in the war. He couldn't be a policeman because the policemen were like his daddy, bullies with clubs who screamed too much. The world, so wonderful to so many, seemed to have made no place in it for him.

"By the way," said the president, leaning forward, "that bourbon you're drinking smells fine to me. I don't blame you. Too many idiots around to get through the day without a sip or two. This is the idiot capital of the world, let me tell you. If I could, if I didn't have to meet with some committee or other, I'd say, come on up to the office, bring your pint, and let's have a spell of sippin'!"

He gave Earl another handshake, and beamed at him with those blue eyes so intense they could see through doors. But then in a magic way, men ge ntly moved among them and seemed to push the president this way, and Earl that. Earl didn't even see who was sliding him through the people, but soon enough he was ferried to the generals, two men so strong of face and eye they seemed hardly human.

"Swagger, you make us proud," one said.

Next page