In memory of

Amanda Saunders (ne Dennys)

19452007

Contents

Over the Border

THE LETTERS OF GRAHAM GREENE

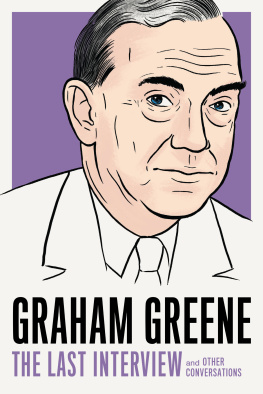

I was present once at a premature cremation, says Aunt Augusta to Henry Pulling, a retired bank manager who has lost the ability to be surprised. And perhaps we believe that we know all we are going to know about Graham Greene, that he has indeed been apprehended by the memoirists and biographers who pursued him. But a journey through his letters which have never before been brought together in one volume reveals him as a fugitive from our inquiries, a most wanted man who has slipped over the border just when we thought to seize him.

It is hard to imagine that the greater part of what Graham Greene wrote in his life remains unpublished. Greene once guessed that he wrote about two thousand letters each year. Some have simply vanished, but many thousands have recently come to light, some in dusty filing cabinets, others in out-of-the-way archives. One extremely important collection of letters to his son, wife and mother was recently discovered inside a hollow book. The sum of all these discoveries is to make Graham Greene a stranger to us again.

Graham Greenes personal letters are written with the wit and passion that made him a great novelist. He records suffering, articulates longing and recounts absurdity. His sense of place mingles vibrancy and horror. While an intelligence officer in Sierra Leone in 1942, he described for his mother the small but ubiquitous movements of decay in the city where he would set The Heart of the Matter:

)

Simply crazy about flying (

In a formal exchange of letters in 1948, he debated with V. S. Pritchett and Elizabeth Bowen the writers obligations to the state: I met a farmer at lunch the other day who was employing two lunatics; what fine workers they were, he said; and how loyal. But of )

Graham Greene is a hard man simply to agree with. His political positions shifted again and again as circumstances altered, and in no small part because he insisted that he wanted to be on the side of victims and that victims change which explains some part of his intellectual history. More fundamental still is Greenes rejection of closed doctrines, including Marxism and, eventually, the Catholic belief in Infallibility. For him, knowledge and belief came in fragments, and they could always fall apart.

Greene tended to the mid-left politically, but took very different views of socialist governments in Mexico, the Soviet Union, Czechoslovakia, Poland, Cuba, Nicaragua, Chile and China, and of insurgencies in Malaya, Vietnam, Kenya, Haiti and El Salvador. Those differences of view were usually shaped by detailed knowledge of situations on the ground. For example, as a vigorous supporter of Israel, he rejected the conventionally pro-Arab views of the European left as uninformed. Of course, Greene had a contrary turn of mind, and some of his decisions are hard to fathom: he refused to visit the Soviet Union during the Brezhnev years because of its treatment of dissidents but sympathised with his old colleague Kim Philby, whose treachery caused many deaths and strengthened the hand of the KGB. Greenes letters from the defector were passed on to MI6 and he made no secret of their communications, so there can be nothing unconsidered in the remark: To me he was a good and loyal friend. (

There is an important paradox here. Although he investigated and poured time and effort into fighting many specific injustices and often Oppression, persecution and poverty make the human heart observable in the writings of Graham Greene, yet the ultimate drama is not that of the masses but of individual men and women.

Many letters in this book discuss problems in the craft of writing. Graham Greene at one time earned a living as an editor and publisher, and he took great pleasure in the fine details of editing he brought to his work a novelists eye and was, for example, willing to chastise one of his discoveries, Mervyn Peake, over the manuscript of Titus Groan: Im going to be mercilessly frank I was very disappointed in a lot of it & frequently wanted to wring your neck because it seemed to me you were spoiling a first-class book by laziness. He said he could not publish it without cuts of ten thousand words of adjectives and prolix dialogue. He ended by cheerfully offering to meet the author in a duel, preferably over whisky glasses in a bar. () And a year later, he did so.

In his letters, Greene, an astute and passionate reader, frequently offers opinions on who is worth reading. A lover of good storytelling above all, he much preferred Arthur Conan Doyle to the grand figures of Bloomsbury: I can reread him as I find myself unable to reread Virginia Woolf and Forster, but then I am not a literary man. () His own canon of modern fiction, which was decidedly international, included R. K. Narayan, the outstanding Indian novelist whom he discovered and promoted in the 1930s. Throughout his career, Narayan relied on Greene to edit his manuscripts, and he even accepted the suggestion that he drop most of the syllables from his name so that elderly librarians would have no trouble ordering his books. Greene also promoted the careers of Muriel Spark and Brian Moore, whom he regarded as the finest novelists of a younger generation. Among the treasures of this volume are his letters to Evelyn Waugh and to Auberon Waugh. No one was better qualified than Greene to judge the merits of fiction, and in his view the finest work of the finest novelist of his time was Brideshead Revisited a novel that has been routinely savaged by lesser critics.

Many readers of this book will want to understand something new about Greenes own writing. In some letters, he explains his intentions for the novels as he either collaborates or disputes with scriptwriters seeking to bring his work to the stage or to the cinema. He answered the letters of many fans who wanted to understand more clearly what they had just read. Greene was never certain whether he would be able to finish any book he had begun or, having finished it, whether it ought to be published. He consistently denigrated his own accomplishments, as when he advised the publisher Peter Owen about translations of Shusaku Endos novel Silence: I still think it very sad that his best book about the Jesuit missionaries never had more than a paperback publication in England. Perhaps one day you could revive it in hardback. A marvellous book so much better than my own Power and the Glory. () A disturbing study of martyrdom in seventeenth-century Japan, Silence is a masterpiece, but Endo could hardly have written it without serving an apprenticeship to Graham Greene.

Greenes misgivings about his work gave way occasionally to rejoicing, as when he suddenly conceived the plot of The Third Man. He wrote in a love letter (of which there are many in this book) to Catherine Walston:

I believe Ive got a book coming. I feel so excited that I spell out your name in full carefully sticking my tongue between my teeth to )

For Greene, the moments of inspiration actually counted for less than the years of unfailing effort often thousands of words per day in his early career and afterwards a daily minimum of five hundred. His labours amounted to a new book almost every year into old age. And, of course, he delighted in praise; in 1949, he told Catherine Walston about a bevy of graduate students in Paris writing on his work: commonsense tells me its all a joke that will soon pass. But I wish you could see the joke too. Id love to preen my feathers in front of you. ()