Carrie Bebris

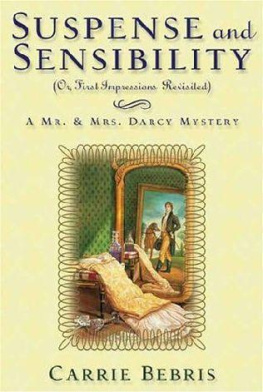

Suspense and Sensibility

Carrie Bebris

Suspense and Sensibility,

or, The First Impressions Revisited

Mr. And Mrs Darcy Book 2

For my sister, Dorothy,

and my grandfather, James Diliberti

Acknowledgments

Many people have contributed to the creation of this book in ways large and small. I particularly wish to thank:

My family, as always, for not only understanding my need to sequester myself away to invent conversations with imaginary people in faraway times and places, but also for encouraging me to do so.

Eliza Diliberti, Victoria Hinshaw, Anne Klemm, and Dorothy Stephenson, for criticism in various stages of the books development. James Lowder, for Latin translations and other shared wisdom. My editor, Brian Thomsen, for his insight and guidance. And Natasha Panza, his extraordinary assistant, for her adept attention to a thousand details.

Members of the Beau Monde chapter of Romance Writers of America, for generously sharing their knowledge of Regency England. Also, my fellow members of the Jane Austen Society of North America, for their continued support.

Jane Austen, for creating Harry Dashwood, Kitty Bennet, and the Darcys. William Shakespeare, for quotes used in Sir Franciss dialogue.

Finally, my readers, for their praise, questions, and feedback. And for their wanting, like me, to spend just a little more time with the Darcys.

"My good opinion once lost is lost for ever."

Darcy to Elizabeth, Pride and Prejudice

O wad some Powr the giftie gie us

To see oursels as others see us!

Robert Burns

Prologue

"There is, I believe, in every disposition a tendency to some particular evil, a natural defect, which not even the best education can overcome."

Darcy to Elizabeth,

Pride and Prejudice, Chapter II

1781

"Damn this mortal coil."

Sir Francis Dashwood muttered the words under his breath, though he had no audience. He sat alone in his bedchamber, surrounded by the opulence hed enjoyed all his life but experiencing the poverty every man knows when his years on earth run out. Time was no longer his to command. Once hed had it in abundance, spent it as liberally and recklessly as any other commodity in his possession. Now it was in dreadfully short supply.

Servants had leit a simple meal on the bedside table. The sandwich went untouched, but the glass of brimstone he drained in two swallows, relishing the familiar taste of the sulfur-laced brandy.

He stared at his reflection in the ornate gilded mirror across from his bed, resenting every wrinkle that etched his ruddy face. Where had that faded hair come from? The liver spots on his hands? The slight tremble that seized his fingers? Eyes watery with age stared back.

As a young man, hed reveled in his vitality. Hed mocked mortality along with morality, dared death and the devil to catch him if they could. Hed lived each moment to its fullest, leaving no desire unindulged, no curiosity unexplored. And he harbored no regrets. If he had his life to live over again, he would change nothing. It had been a good run.

But it was not enough.

Fiery orange light slanted through the window to stripe the floor. Sunset might claim the bleak late autumn landscape of West Wycombe Park, but it would not claim him so easily. No, he would not go quietly into the darkness. His spirit was too strong to meekly concede the battle his body waged with time.

He gazed beyond his own image in the glass, to the reflection of the portrait that hung behind him. That, too, was an image of himself, but at one-and-twenty. The painter had captured him in the full vigor of youth. Just as the adventure that had been his life was beginning.

Inside, he was still I hat young man. Yet now he scarcely had the strength to even rise from his bed.

He twisted the sheets with arthritic hands, cursing his physical weakness, cursing the corporeal shell that could no longer keep up with him. He cursed the mirror that bore witness to his frailty. Hed paid handsomely for the artifact, one of many treasures that hed acquired in his lifetime. Hed been drawn to it by the images of ancient Greek champions that adorned its frame, but now they seemed to taunt him with their puissance. Tonight, he would gladly trade the mirror nay, his whole estate to inhabit once more the body of a young man, to again take health and strength for granted.

He could not tear his gaze away from the reflections: Two images of the same man, separated by mere inches but a gulf of more than fifty years. Dawn and twilight.

He wanted another sunrise.

His vision grew cloudy, as it often did now at the end of the day. The dual images of himself became less distinct, fading at their edges and drifting toward each other. He blinked rapidly and rubbed his eyes, trying to stabilize the view, but in vain. His eyesight, like the rest of his body, was failing him.

This last failure, however, was welcome, for after another minute, the two images merged completely. Despair fled, replaced by satisfaction.

Slowly, a smile spread across his face. He was a young man once more.

If only in the mirror.

One

"If any young men come for Mary or Kitty,

send them in, for I am quite at leisure."

Mr. Bennet to Elizabeth,

Pride and Prejudice, Chapter 59

1813

Elizabeth Bennet Darcy tried very hard to concentrate on the letter in her hand, but the intrusion of her own thoughts conspired with the fine prospect outside her window to distract her.

When the post arrived, she had withdrawn to her favorite sitting room at Pemberley. Such had become her morning custom in her few months as mistress of the house. The room, she understood, had also been a favorite of her husbands mother, and Elizabeth suspected the late Mrs. Darcy had shared her opinion that it offered a view of the river and valley superior to any other in the house. Today, though patches of snow stubbornly resisted the caress of the late winter sun, the smell of damp earth nevertheless carried the promise of spring.

Fitzwilliam Darcys ancestral house bore the imprint of so many generations that Elizabeth had not yet found her place here. Home was anywhere her husband was, and Darcy had done much to ease her way, but the greatness of his estate required her adjustment. She did not want to depart Pemberley before she truly felt settled. But family duty beckoned, and they were obliged to answer.

She left the window, returned to her desk, and read once more the cross-written, blotted lines. As she contemplated her response, Darcy entered. His tailcoat, leather breeches, and top boots indicated his intent to go riding.

"Good morning, again." Darcy kissed her cheek. "I came to invite you for an airing."

She set aside the letter with a heavy sigh.

A frown creased his forehead. "Perhaps instead I should enquire what I have done to merit such a reception? I realize riding was never your favorite pastime, but I do not recall your ever greeting the suggestion with despondency before."

"It is not your invitation that dismays me." Under her husbands influence, shed developed greater interest in riding, though in truth, it was the company more than the activity that appealed to her. She looked up into his face and smiled wistfully. "I am afraid, sir, that you have committed crimes of a more grievous nature."

"Indeed?" He set down his hat and leaned against the edge of her desk. "Name the offenses."

"Like a nursery-tale knave, you have carried me off to your secluded castle and kept me to yourself for nigh on three months, with no thought of returning me to the companionship of my family."