ALSO BY GEORGE ORWELL

fiction

Burmese Days

A Clergymans Daughter

Keep the Aspidistra Flying

Coming Up for Air

Animal Farm

Nineteen Eighty-Four

non-fiction

Down and Out in Paris and London

The Road to Wigan Pier

Homage to Catalonia

A Kind of Compulsion (190336)

Facing Unpleasant Facts (193739)

A Patriot After All (194041)

All Propaganda Is Lies (1941 42)

Keeping Our Little Corner Clean (194243)

Two Wasted Years (1943)

I Have Tried to Tell the Truth (194344)

I Belong to the Left (1945)

Smothered Under Journalism (1946)

It Is What I Think (194748 )

Our Job Is to Make Life Worth Living (194950)

Critical Essays

Narrative Essays

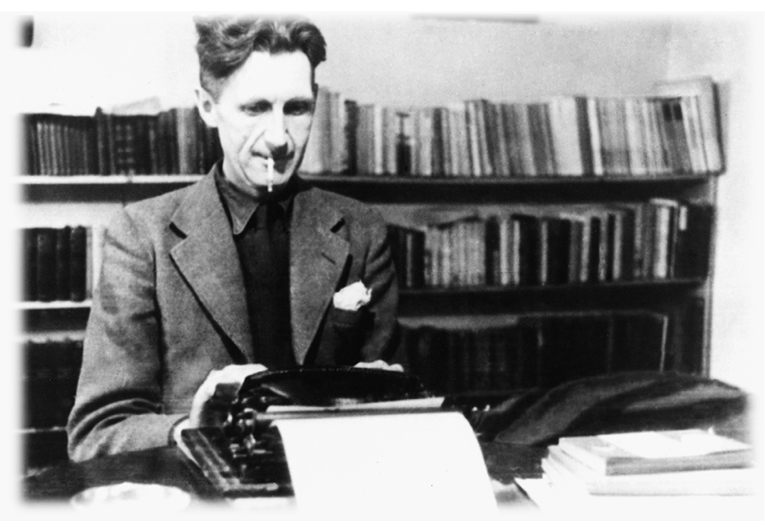

GEORGE ORWELL

Diaries

EDITED BY

PETER DAVISON

Introduction by Christopher Hitchens

LIVERIGHT PUBLISHING CORPORATION

A Division of W. W. Norton & Company

New York London

Contents

Introduction

by Christopher Hitchens

A t various points in his essays notably in Why I Write but also in his popular occasional column As I Please George Orwell gave us an account of what made him tick, as it were, and of what supplied the motive for his work. At different times he instanced what he called his power of facing unpleasant facts, his love for the natural world, growing things and the annual replenishment of the seasons, and his desire to forward the cause of democratic socialism and oppose the menace of Fascism. Other strong impulses include his near-visceral feeling for the English language and his urge to defend it from the constant encroachments of propaganda and euphemism, and his reverence for objective truth, which he feared was being driven out of the world by the deliberate distortion and even obliteration of recent history.

As someone who had been brought up in a fairly rarefied and distinctly reactionary English milieu, in which the underclass of his own society and the millions of inhabitants of its colonial empire were regarded with a mixture of fear and loathing, Orwell also made an early decision to find out for himself what the living conditions of these remote latitudes were really like. This second commitment, to acquaint himself with the brute facts as they actually were, was to prove a powerful reinforcement of his latent convictions.

Read with care, these diaries from the years 1931 to 1949 can greatly enrich our understanding of how Orwell transmuted the raw material of everyday experience into some of his best-known novels and polemics. They also furnish us with a more intimate picture of a man who, committed to the struggles of the mechanized and modern world, was also drawn by the rhythms of the wild, the rural and the remote. (He barely survived into the first month of the second half of the twentieth century, dying of the sort of poverty-induced disease that might have killed a character out of Dickens. Yet despite his Edwardian and near-Victorian provenance he remains more contemporary and relevant to us than many authors of a much later date.)

This diary is not by any means a straight guide, or a trove of clues and cross-references. It would be rather difficult to deduce, for example, that it was during his sojourn in Morocco in 19381939 that Orwell conceived and composed the novel Coming Up for Air . This short and haunting work involves an evocation of a lost bucolic England set in the barely imaginable years before the drama of the First World War. For it to have been written amid the torrid souk of Marrakech and the arid emptiness of the Atlas mountains must have involved some convolutions of the creative process into which he gives us little or no insight. But he was also in Morocco in addition to being in search of a cure for his gnawing tuberculosis to make notes and take soundings about the conditions of North African society.

Indeed, the thirties were the decade during which Orwell took up the task of amateur anthropologist, both in his own country and overseas. Sometimes attempting to disguise his origins as an educated member of the upper classes and former colonial policeman (he is amusing about his attempts to flatten his accent according to the company he was keeping), he set off to amass notes and absorb experiences. I mentioned earlier that his family background, the income of which depended on the detestable opium trade between British-ruled India and British-influenced China, had at first conditioned him to fear and despise the locals and the natives. One of the many things that made Orwell so interesting was his self-education away from such prejudices, which also included a marked dislike of the Jews. But anyone reading the early pages of these accounts and expeditions will be struck by how vividly Orwell still expressed his unmediated disgust at some of the human specimens with whom he came into contact. When joining a group of itinerant hop-pickers he is explicitly repelled by the personal characteristics of a Jew to whom he cannot bear even to give a name, characteristics which he somehow manages to identify as Jewish. He is unsparing about the sheer stupidity and dirtiness of so many of the proletarian families with whom he lodges, and is sometimes condescending about the extreme limitations of their education and imagination. The failure of The Road to Wigan Pier was partly attributable to a successful Communist campaign to defame it (and him) for saying that the working classes smell. Orwell never actually did say this, except in the oblique context of denouncing those who did, but his own slightly wrinkled nostrils must have helped a little in the spread of the slander.

It may not be too much to claim that by undertaking these investigations, Orwell helped found what we now know as cultural studies and postcolonial studies. His study of unemployment and poor housing in the north of England stands comparison, with its careful statistics, with Friedrich Engelss Condition of the English Working Class , published a generation or two earlier. But with its additional information and commentary about the reading and recreational habits of the workers, the attitudes of the men to their wives and the mixtures of expectation and aspiration that lent nuance and distinction to the undifferentiated concept of the proletariat, we can see the accumulation of debt that later social authors and analysts, such as Michael Young and Richard Hoggart, owed to Orwell when they began their own labours in the postwar period. We can also feel, in the increasingly stubborn growth of his egalitarian and socialist principles during these years, the germination of one of the most famous lines of Nineteen Eighty-Four : If there is hope, it lies in the proles. From a detail in the life of the British coal miner does he have the right to a cleansing bath at the pithead, and if so, does he pay for it out of his own wages and in his own time? Orwell illustrates the potential power of the working class to generate its own resources out of an everyday struggle, but also to generalize that quotidian battle for the resolution of greater and nobler matters such as the ownership of production and the right to labours full share.

Similarly in North Africa, Orwell continued down the track on which he had begun when he declared his own independence from the British colonial system in Indo-China. (It is often forgotten that one of his first published researches, written in French and published by a small radical house in Paris, was about the way in which Britains exploitation perpetuated the underdevelopment of Burma.) The sexual and racial implications of the exertion of colonial power he reserved for his first novel Burmese Days but he never lost sight of the importance of the economic substratum, and in his comparatively brief sojourn in Morocco was also highly interested in the ethnic composition of the population and in such seemingly arcane matters as the circulation wars between the different language groups and political factions, as reflected in the sales of local newspapers. Again, though, one notices a certain fastidious preoccupation with the stench of poverty and squalor, including some pungent reflections on the discrepant scents of Jewish and Arab ghettos.

Next page