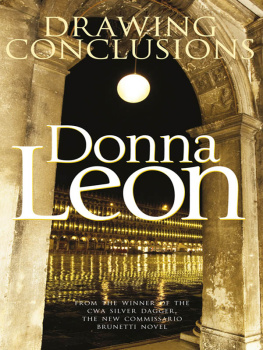

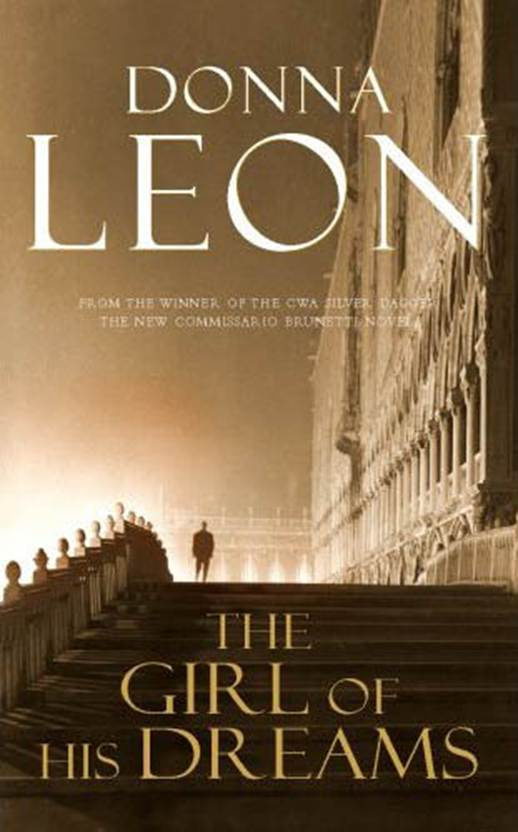

Donna Leon

The Girl of his Dreams

Commissario Guido Brunetti 17, 2008

Der Tod macht mich nicht beben.

Nur meine Mutter dauert mich;

Sie stirbt vor Gram ganz sicherlich.

Death does not make me tremble.

I feel sorry only for my mother.

She will surely die of grief.

Die Zauberflote Mozart

Brunetti found that counting silently to four and then again and again allowed him to block out most other thoughts. It did not obscure his sight, but it was a day rich with the grace and favour of springtime, so as long as he kept his eyes raised above the heads of the people around him, he could study the tops of the cypress trees, even the cloud-dappled sky, and what he saw he liked. Off in the distance, if only he turned his head a little, he could see the inside of the brick wall and know that beyond it was the tower of San Marco. The counting was a sort of mental contraction, akin to the way he tightened his shoulders in cold weather in the hope that, by decreasing the area exposed to the cold, he would suffer it less. Thus, here, exposing less of his mind to what was going on around him might diminish the pain.

Paola, on his right, slipped her arm through his, and together they fell into step. On his left were his brother

Sergio, Sergio's wife, and two of their children. Raffi and Chiara walked behind him and Paola. He turned and glanced back at the children and smiled: a frail thing, quickly dissipated in the morning air. Chiara smiled back; Raffi lowered his eyes.

Brunetti pressed his arm against Paola's, looking down at the top of her head. He noticed that her hair was tucked behind her left ear and that she was wearing the gold and lapis earrings he had given her for Christmas two years before. The blue of the earring was lighter than her dark blue coat: she had worn that and not the black one. When had it stopped, he wondered, the unspoken demand that black be worn at funerals? He remembered his grandfather's funeral, with everyone in the family, especially the women, draped in black and looking like paid mourners in a Victorian novel, though that had been well before he knew anything about the Victorian novel.

His grandfather's older brother had still been alive then, he remembered, and had walked behind the casket, in this same cemetery, under these same trees, behind a priest who must have been reciting the same prayers. Brunetti remembered that the old man had brought a clod of earth from his farm on the outskirts of Dolo -long gone now and paved over by the autostrada and the factories. He recalled the way his great-uncle had taken his handkerchief from his pocket as they stood silently around the open grave as the coffin was lowered into it. And he remembered the way the old man he must have been ninety, if a day had folded back the fabric and taken out a small clod of earth and dropped it on to the top of the coffin.

That gesture remained one of the haunting memories of his childhood, for he never understood why the old man had brought his own soil, nor had anyone in the family ever been able to explain it to him. He wondered, standing there now, whether the whole scene could have been nothing more than the imagination of an overwrought child, struck into silence by the sight of most of the people he knew shrouded in black and by the confusion that had resulted from his mother's attempt to explain to his six-year-old self what death was.

She knew now, he supposed. Or not. Brunetti was prone to believe that the awfulness of death lay precisely in the absence of consciousness, that the dead ceased to know, ceased to understand, ceased to anything. His early life had been filled with myth: the little Lord Jesus asleep in his bed, the resurrection of the flesh, a better world for the good and faithful to go to.

His father, however, had never believed: that had been one of the constants of Brunettes childhood. He was a silent non-believer who made no comment on his wife's evident faith. He never went to church, absented himself when the priest came to bless the house, did not attend his children's baptisms, first communions, or confirmations. When asked about the subject, the elder Brunetti muttered, 'Sciocchezze or 'Roba da donne', and did not pursue the topic, leaving his two sons to follow him if they wanted in the conviction that religious observation was the foolish business of women, or the business of foolish women. But they'd got him in the end, Brunetti reflected. A priest had gone into his room in the Ospedale Civile and given the dying Brunetti the last rites, and a mass had been said over his body.

Perhaps all of this had been done to console his wife. Brunetti had seen enough of death to know what a great comfort faith can be to those left behind. Perhaps this had been in the back of his mind during one of the last conversations he had with his mother, well, one of the last lucid ones. She had still been living at home, but already her sons had had to hire the daughter of a neighbour to come and spend the days with her, and then the nights.

In that last year, before she had slipped away from them entirely and into the world where she had spent her last years, she had stopped praying. Her rosary, once so treasured, had gone; the crucifix had disappeared from beside her bed; and she had stopped attending Mass, though the young woman from downstairs often asked her if she would like to go.

'Not today she always answered, as if leaving open the possibility of going tomorrow, or the next day. She had stuck with this answer until the young woman, and then the Brunetti family, stopped asking. It did not put an end to their curiosity about her state of mind, only to its outward manifestation. As time passed, her behaviour became more alarming: she had days when she did not recognize either of her sons and other days when she did and talked quite happily about her neighbours and their children. Then the proportion shifted, and soon the days when she knew her sons or remembered that she had neighbours grew fewer. On one of those last days, a bitter winter day six years before, Brunetti had gone to see her in the late afternoon, for tea and for the small cakes she had baked that morning. It was by chance that she had baked the cakes; really she had been told three times that he was coming, but she had not remembered.

As they sat and sipped, she described a pair of shoes she had seen in a shop window the day before and had decided she would like to buy. Brunetti, even though he knew she had not been out of her home for six months, offered to go and get them for her, if she would tell him where the shop was. The look she gave him in return was stricken, but she covered it and said that she would prefer to go back herself and try them on to be sure they fitted.

She looked down into her teacup after saying that, pretending not to have noticed her lapse of memory. To relieve the tension of the moment, Brunetti had asked, out of the blue, 'Mamma, do you believe all that stuff about heaven and living on after?'

She raised her eyes to look at her younger son, and he noticed how clouded the iris had become. 'Heaven?' she asked.

'Yes. And God Brunetti answered. 'All that.'

She took a small sip of tea and leaned forward to set her cup in her saucer. She pushed herself back: she always sat up very straight, right to the end. She smiled then, the smile she always used when Guido asked one of his questions, the ones that were so hard to answer. 'It would be nice, wouldn't it?' she answered and asked him to pour her more tea.

He felt Paola stop beside him, and he came to a halt, pulled back from memory and suddenly attentive to where they were and what was going on. Off in the corner, in the direction of Murano, there was a tree in blossom. Pink. Cherry? Peach? He wasn't sure, didn't know a lot about trees, but he was glad enough of the pink, a colour his mother had always liked, even though it didn't suit her. The dress she wore inside that box was grey, a fine summer wool she had had for years and worn only infrequently, joking that she wanted to keep it to be buried in. Well.

Next page