Charlaine Harris

Shakespeares Trollop

The fourth book in the Lily Bard series, 2000

This book is dedicated to my other family, the people of St. James Episcopal Church. They are at liberty to be horrified by its contents.

My thanks to the usual suspects: Drs. Aung and Tammy Than and former police chief Phil Gates. My further thanks to an American icon, John Walsh.

***

By the time I opened my eyes and yawned that morning, she had been sitting in the car in the woods for seven hours. Of course, I didnt know that, didnt even know Deedra was missing. No one did.

If no one realizes a person is missing, is she gone?

While I brushed my teeth and drove to the gym, dew must have been glistening on the hood of her car. Since Deedra had been left leaning toward the open window on the drivers side, perhaps there was dew on her cheek, too.

As the people of Shakespeare read morning papers, showered, prepared school lunches for their children, and let their dogs out for a mornings commune with nature, Deedra was becoming part of nature herself-deconstructing, returning to her components. Later, when the sun warmed up the forest, there were flies. Her makeup looked ghastly, since the skin underlying it was changing color. Still she sat, unmoving, unmoved: life changing all around her, evolving constantly, and Deedra lifeless at its center, all her choices gone. The changes she would make from now on were involuntary.

One person in Shakespeare knew where Deedra was. One person knew that she was missing from her normal setting, in fact, missing from her life itself. And that person was waiting, waiting for some unlucky Arkansan-a hunter, a birdwatcher, a surveyor-to find Deedra, to set in motion the business of recording the circumstances of her permanent absence.

That unlucky citizen would be me.

If the dogwoods hadnt been blooming, I wouldnt have been looking at the trees. If I hadnt been looking at the trees, I wouldnt have seen the flash of red down the unmarked road to the right. Those little unmarked roads- more like tracks-are so common in rural Arkansas that theyre not worth a second glance. Usually they lead to deer hunters camps, or oil wells, or back into the property of someone who craves privacy deeply. But the dogwood I glimpsed, perhaps twenty feet into the woods, was beautiful, its flowers glowing like pale butterflies among the dark branchless trunks of the slash pines. So I slowed down to look, and caught a glimpse of red down the track, and in so doing started the tiles falling in a certain pattern.

All the rest of my drive out to Mrs. Rossiters, and while I cleaned her pleasantly shabby house and bathed her reluctant spaniel, I thought about that flash of bright color. It hadnt been the brilliant carmine of a cardinal, or the soft purplish shade of an azalea, but a glossy metallic red, like the paint on a car.

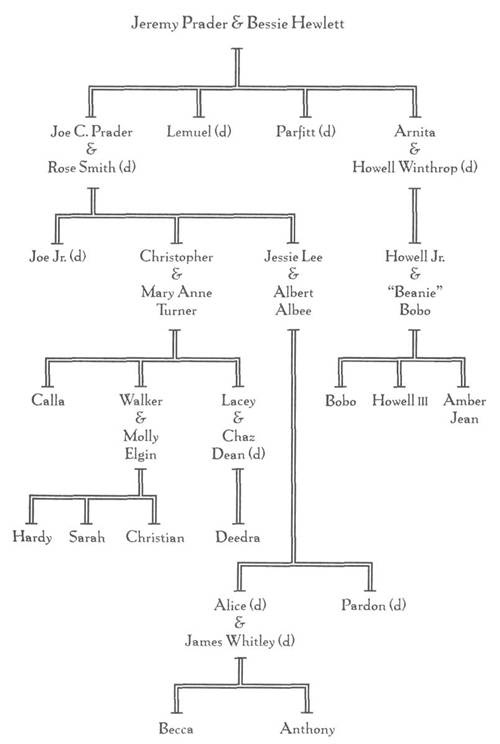

In fact, it had been the exact shade of Deedra Deans Taurus. There were lots of red cars in Shakespeare, and some of them were Tauruses. As I dusted Mrs. Rossiters den, I scorned myself for fretting about Deedra Dean, who was chronologically and biologically a woman. Deedra did not expect or require me to worry about her and I didnt need any more problems than I already had.

That afternoon, Mrs. Rossiter provided a stream-of-consciousness commentary to my work. She, at least, was just as always: plump, sturdy, kind, curious, and centered on the old spaniel, Durwood. I wondered from time to time how Mr. Rossiter had felt about this when hed been alive. Maybe Mrs. Rossiter had become so fixated on Durwood since her husband had died? Id never known M. T. Rossiter, who had departed this world over four years ago, around the time Id landed in Shakespeare. While I knelt in the bathroom, using the special rinse attachment to flush the shampoo out of Durwoods coat, I interrupted Mrs. Rossiters monologue on next months Garden Club flower show to ask her what her husband had been like.

Since Id stopped her midflow, it took Birdie Rossiter a moment to redirect the stream of conversation.

Well my husband its so strange you should ask, I was just thinking of him

Birdie Rossiter had always just been thinking of whatever topic you suggested.

M. T. was a farmer.

I nodded, to show I was listening. Id spotted a flea in the water swirling down the drain and I was hoping Mrs. Rossiter wouldnt see it. If she did, Durwood and I would have to go through various unpleasant processes.

He farmed all his life, he came from a farming family. He never knew anything else but country. His mother actually chewed tobacco, Lily! Can you imagine? But she was good woman, Miss Audie, with a good heart. When I married M. T.-I was just eighteen-Miss Audie told us to build a house wherever on their land we pleased. Wasnt that nice? So M. T. picked this site, and we spent a year working on the floor plan. And it turned out to be an ordinary old house, after all that planning! Birdie laughed. Under the fluorescent light of the bathroom, the threads of gray in the darkness of her hair shone so brightly they looked painted.

By the time Birdie had reached the point in her husbands biography where M. T. was asked to join the Gospellaires, a mens quartet at Mt. Olive Baptist, I had begun my next grocery list, at least in my head.

An hour later, I was saying good-bye, Mrs. Rossiters check tucked in the pocket of my blue jeans.

See you next Monday afternoon, she said, trying to sound offhand instead of lonely. Well have our work cut out for us then, because itll be the day before I have the prayer luncheon.

I wondered if she would want me to put bows on Durwoods ears again, like I had the last time Birdie had hosted the prayer luncheon. The spaniel and I exchanged glances. Luckily for me, Durwood was the kind of dog who didnt hold a grudge. I nodded, grabbed up my caddy of cleaning products and rags, and retreated before Mrs. Rossiter could think of something else to talk about. It was time to get to my next job, Camille Emersons. I gave Durwood a farewell pat on the head as I opened the front door. Hes looking good, I offered. Durwoods poor health and bad eyesight were a never-ending worry to his owner. A few months before, hed tripped Birdie with his leash and shed broken her arm, but that hadnt lessened her attachment to the dog.

I think hes good as gold, Birdie told me, her voice firm. She stood on her front porch watching me as I put my supplies in the car and slid into the drivers seat. She laboriously squatted down by Durwood and made the dog raise his paw and wave good-bye to me. I lifted my hand: I knew from experience that she wouldnt stop Durwoods farewell until I responded.

As I thought about what I had to do next, I was almost tempted to turn off the engine and sit longer, listening to the ceaseless stream of Birdie Rossiters talk. But I started the car, backed out of her driveway, and looked both ways several times before venturing out. There wasnt much traffic on Farm Hill Road, but what there was tended to be fast and careless.

I knew that when I drew opposite the unmarked road, I would stop on the narrow grassy shoulder. My window was open. When I cut my engine, the silence took over. I heard nothing.

I got out and closed the door behind me. A breeze lifted my short, curly hair and made my T-shirt feel inadequate. I shivered. The tingling feeling at the back of my neck was warning me to drive off but sometimes, I guess, you just cant dodge the bullet.

Next page