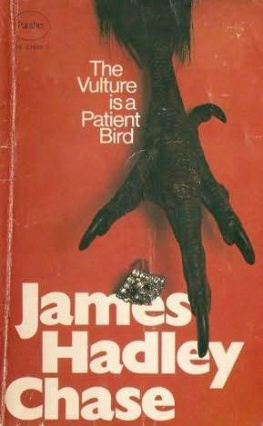

James Hadley Chase

THE VULTURE IS A PATIENT BIRD

His built-in instinct for danger brought Fennel instantly awake. He raised his head from the pillow and listened. Black darkness surrounded him: the darkness of the blind. Listening, he could hear the gentle slap-slap of water against the side of the moored barge. He could hear Mimis light breathing. There was also a slight rhythmetic creaking as the barge heaved in the swell of the river. He could also hear rain falling lightly on the upper deck. All these sounds were reassuring. So why then, he asked himself, had he come so abruptly awake?

For the past month he had lived under the constant threat of death, and his instincts had sharpened. Danger was near: he felt it. He imagined he could even smell it.

Silently, he reached down and groped under the bed until his fingers closed around the handle of a police baton. Attached to the end of the baton was a short length of bicycle chain. This chain turned the baton into a deadly, vicious weapon.

Gently, so as not to disturb the sleeping woman at his side, Fennel raised the sheet and blanket and slid out of bed.

He was always meticulously careful to place his clothes on a chair by the bed: no matter where he stayed. To find his clothes, to dress quickly in the dark was vitally important when living under the threat of death.

He slid into his trousers and into rubber soled shoes. The woman in the bed moaned softly and turned over. Holding the flail in his right hand, he moved silently to the door. He had learned the geography of the barge and the solid darkness didnt bother him. He found the well greased bolt and drew it back, then his fingers found the door handle and turned it. Gently, he eased open the door a few inches. He peered out into the rain and darkness. The slapping sound of water against the side of the barge, the increased sound of the rain blotted out all other sounds, but this didnt deceive Fennel. There was danger out there in the darkness. He could feel the shorthairs on the nape of his neck bristling.

Cautiously, he opened the door wider so that he could see the full length of the deck faintly outlined by the street lights of the embankment. To his left, he could see the glow of light from Londons West-end. Again he listened; again he heard nothing to alarm him. But the danger was there he was sure of it. He crouched, lay flat and slid out on to the cold, wet deck. Rain pattered down on his naked, powerful shoulders. He edged forward, then his lips came off his even white teeth in a snarl.

Some fifty metres from the moored barge, he could see a rowing boat drifting towards him. There were four powerfully built men crouching in the boat. He could see the outline of their heads and their shoulders against the glow of the distant lights. One of the men was using an oar to direct the boat towards the barge: his movements were careful and silent.

Fennel slid further on to the deck. His fingers tightened on the handle of the flail. He waited.

It would be wrong to describe Fennel as courageous as it would be wrong to describe a leopard as courageous. The leopard will run when it can, but when cornered, it becomes one of the most dangerous and vicious of all jungle beasts. Fennel was like the leopard. If he saw a way out, he ran, but if he were trapped, he turned into a nerveless animal determined only no matter the means on self preservation.

Fennel had known sooner or later they would find him. Well, they were here, drifting silently towards him. Their approach left him only with a vicious determination to protect himself. He was not frightened. He had been purged of fear once he knew for certain that Moroni had decreed that he should die.

He watched the boat as it drifted closer. They knew he was dangerous, and they were taking no risks. They wanted to get aboard, make a quick dash down into the bedroom and then the four of them would smother him while their knives carved him.

He waited, feeling the rain cold on his naked shoulders. The man with the oar dipped the blade and made a gentle stroke. The boat heaved over the wind-swept water at a faster rate.

Fennel was invisible in the shadows. He decided he had judged his position accurately. They would board the barge about four metres from where he was lying.

The rower shipped the oar and laid it gently as if it were made of spun sugar along the three seats of the boat. He now had enough way to bring the boat to the side of the barge.

The man sitting on the front seat stood up and leaned forward. He eased the boat against the side of the barge, then with an athletic spring, he came aboard. He turned and caught the hand of the second man who moved forward. As he was helping him on to the deck, Fennel made his move.

He rose up out of the darkness, slid across the slippery deck and slashed with the flail.

The chain caught the first man across his face. He gave a wild yell, staggered, then pitched into the river.

The second man, his reflexes swift, spun around, knife in hand to face Fennel, but the chain slashed him around the neck, tearing his skin and sending him reeling back. He clutched at nothing, then went into the water, flat on his back.

Fennel darted into the shadows. His grin was vicious and evil. He knew the other two men in the boat couldnt see him. The light was behind them.

There was a moment of confusion. Then frantically, the man who had used the oar, grabbed it and began to pull away from the barge. The other man was trying to get his companions out of the river into the boat.

Fennel lay watching. His heart was hammering, and his breathing came in jerky snorts through his wide nostrils.

The two men were dragged aboard. The rower had the second oar now in the rowlock and was pulling away from the barge. Fennel remained where he was. If they saw him, they might risk a shot. He waited, shivering in the cold, until the boat disappeared into the darkness, then he got to his feet.

He leaned over the side of the barge to wash the blood off the chain. He felt the icy rain sliding down inside his trousers. He thought they might come back later, and if they did, the odds would be stacked against him. They would no longer be taken by surprise.

He shook the rain out of his eyes. He must get out, and get out fast.

He went down the eight steps into the big living and bedroom and flicked on the light.

The woman in bed sat up.

What is it, Lew?

He paid no attention to her. He stripped off his sodden trousers and walked naked into the small bathroom. God! He was cold! He turned on the hot shower tap, waited a moment, then stepped under the healing hot spray.

Mimi came into the bathroom. Her eyes were drugged with sleep, her long black hair touselled, her big breasts escaping from her nightdress.

Lew! What is it?

Fennel ignored her. He stood, thick, massive and short, under the hot spray of water, letting the water soak the thick hairs on his chest, belly and loins.

Lew!

He waved her away, then turned off the shower and took up a towel.

But she wouldnt go away. She stood outside the bathroom, staring at him, her green, dark ringed eyes alight with fear.

Get me a shirt dont stand there like a goddam dummy!

He threw aside the towel.

What happened? I want to know. Lew! Whats going on?

He pushed past her and walked into the inner room. He jerked open the closet door, found a shirt and struggled into it, found a pair of trousers and slid into them. He pulled on a black turtle neck sweater, then shrugged himself into a black jacket with leather patches on the elbows. His movements were swift and final.

She stood in the doorway, watching.

Why dont you say something? Her voice was shrill. Whats happening?

He paused for a brief moment to look at her and he grimaced. Well, she had been convenient, he told himself, but no man in his right mind could call her an oil painting. Still, she had provided him with a hideout on this crummy barge for the past four weeks. Right now, without her plaster of make-up, she looked like hell. She was too fat. Those sagging breasts sickened him. Her anxious terror aged her. What was she forty? But she had been convenient. It had taken Moroni four weeks to find him, but now it was time to leave. In three hours, Fennel thought, probably less, she would not even be a memory to him.