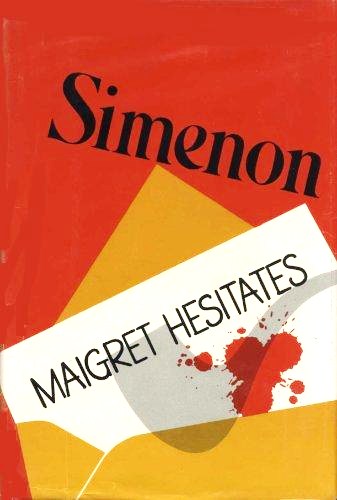

Georges Simenon

Maigret Hesitates

A book in the Inspector Maigret series

1968

An anonymous letter, that tells of a soon to be committed murder, takes inspector Maigret to the home of a prominent lawyer on his search for the letter's author.

ONE

H ello, Janvier.

Good morning, Chief.

Good morning, Lucas. Good morning, Lapointe

Maigret couldnt keep back a smile as he reached the latter. Not only because young Lapointe was wearing a slim-fitting new suit, pale gray with tiny flecks of red. Everyone was smiling that morning, in the streets, in the buses, in the shops.

The day before had been a gray and windy Sunday, with wintry squalls of rain, and suddenly, although it was only the fourth of March, they had wakened to find it was spring.

The sun was still a bit sharp, certainly, and the blue sky brittle, but there was a gaiety in the air, in the eyes of the passers-by, a sort of complicity in the joie de vivre and in recognizing anew the delicious smells of Paris in the morning.

Maigret had come out without a coat and had walked a good part of the way. As soon as he had come into the office he had opened the window. The Seine had changed color too; the red lines on the funnels of the tugs were brighter, the barges like new again.

He had opened the door of the inspectors office.

Are you coming in, boys?

It was what they called the little briefing, in contrast to the real briefing, which got all the divisional superintendents together with the big chief. Maigret called his closest associates together.

Did you have a good day yesterday? he asked Janvier.

We took the children to my mother-in-laws, at Vaucresson.

Lapointe, uncomfortable in his new suit, which was a little too summery, kept in the background.

Maigret sat down at his desk, filled a pipe, and began to go through his mail.

Thats for you, Lucas. Its about the Lebourg case.

He held some other papers out to Lapointe.

Take these to the Public Prosecutors Office.

You couldnt say there was foliage yet, but there was just a touch of pale green on the trees along the quay.

There was no big case on at the moment, none of those cases that filled the hallways of the Criminal Police with reporters and photographers and which provoked peremptory telephone calls from high places. Only ordinary things. Cases to be followed up

A madman, or a madwoman, he pronounced as he picked up an envelope on which his name and the address of the Quai des Orfvres were written in block capitals.

The envelope was white, of good quality. The stamp was canceled with the postmark of the post office in the Rue de Miromesnil. What struck the superintendent first, on pulling the letter out, was the paper, a thick, crackly vellum of an unusual shape. Someone must have cut off an engraved letterhead, and this task had been done with care, using a ruler and a very sharp knife.

The text of the letter, like the address, was in very regular block capitals.

Perhaps not such a madman, he growled.

Dear Divisional Superintendent,

I do not know you personally, but what I have read of your investigations and of your attitude to criminals gives me confidence. This letter will astonish you. Do not throw it into the waste-paper basket too quickly. It is not a joke, nor is it the work of a maniac.

You know better than I do that the truth is not always credible. A murder will be committed shortly, certainly within a few days. Perhaps by someone known to me, perhaps by me myself.

I am not writing to you so that the murder will not take place. It is in a way inevitable. But when it happens I would like you to know.

If you take me seriously, please put the following advertisement in the personal column of Le Figaro or Le Monde: K.R. I am waiting for a second letter.

I do not know if I shall write it. I am very worried. Certain decisions are hard to make.

I may perhaps see you one day, in your office, but then we shall be on opposite sides of the fence.

Yours faithfully.

He wasnt smiling any more. Frowning, he gave the sheet of paper another glance, then looked at his associates.

No, I dont think its a madman, he repeated. Listen. He read it to them, slowly, emphasizing certain words. He had had letters of this kind before, but most of the time the language was less well chosen and usually certain phrases had been underlined. They were often written in red or green ink and many of them had spelling mistakes.

The hand had not trembled here. The strokes were firm, with no flourishes or erasures.

He held the paper up to the light and read the watermark: Morvan Vellum.

He got hundreds of anonymous letters every year. With very rare exceptions, they were written on cheap paper sold at any corner store, and sometimes the words were cut out of newspapers.

No specific threat, he murmured. A sense of hopeless distressLe Figaro and Le Monde, two daily papers read largely by the intellectual bourgeoisie

He looked at all three men again.

Will you see to it, Lapointe? The first thing to do is to get in touch with the paper manufacturer, who must be somewhere in the Morvan.

Right, Chief.

That was the beginning of a case which was going to give Maigret more worries than many front-page crimes.

Put the advertisement in.

In the Figaro?

In both papers.

A bell rang for the briefing, the real one, and Maigret, file in hand, went to the directors office. Here too the open window was letting the sounds of the city steal in. One of the superintendents was sporting a sprig of mimosa in his buttonhole, and he felt obliged to explain:

Theyre selling them in the street for some charity

Maigret did not mention the letter. His pipe was good. He watched the faces of his colleagues lazily as they set out the details of their cases in turn, and he made a mental calculation of the number of times he had been present at the same ceremony. Thousands.

But much more often he had envied the divisional superintendent who had been his chief, as he went every morning to the holy of holies. Wouldnt it be wonderful to be Chief of the Crime Squad? He hadnt dared to dream of that then, no more than Lapointe or Janvier or even Lucas did now.

It had happened all the same, and after so many years he didnt even think about it any more, except on a morning like this, when the air smelled sweet and when, instead of swearing at the roar of the buses, people smiled.

When he got back to his office half an hour later, he was surprised to find Lapointe there, standing in front of the window. His fashionable suit made him look thinner, taller, much younger. Twenty years before, a detective-inspector wouldnt have been allowed to dress like that.

That was almost too easy, Chief.

You found who makes the paper?

Gron and Sons, who have had the Morvan Paper Mills at Autun for three or four generations. Its not a factoryits all done by craftsmen. The paper is handmade, whether its for de luxe editions, usually books of poems, it seems, or for writing paper. The Grons have no more than ten people working there. From what I was told, there are still a few paper mills like that in the region.

Did you get the name of their agent in Paris?

They dont have an agent. They work directly with art publishers and with two stationers, one on Rue du Faubourg-Saint-Honor, the other on Avenue de lOpra.

Isnt that right at the top of Rue du Faubourg-Saint-Honor, on the left?

I think so, from the addressThe Papeterie Roman.