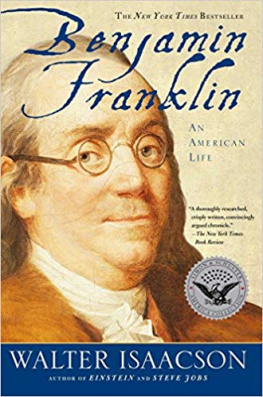

To be born in Boston on Sunday, January 6, 1706, meant for Benjamin Franklin to brave the frigid waters of Puritan baptism. When his mother, Abiah, finished winding newborn Benjamin in swaddling clothes, his father, Josiah bundled the baby under his heavy cape. Then Franklin and his other children stepped across the icy paving stones into unheated Old South Church. After a three-hour Sabbath service, the congregation crowded to the rear to bear witness as the pastor cracked the ice in the baptismal font. Murmuring the words intended to save the babys soul, if not his shivering body, he splashed hours-old Benjamin. Then Josiah, a town constable, led a hymn of joy. His tenth son would be his offering of thanksgiving to God, go to Harvard, and become a minister of the Puritan church.

When Josiah Franklin, a fabric dyer, arrived in Boston from England with his first wife Anne, he learned, for the first time, that brightly colored fabrics were forbidden by the Puritans. He needed a new trade, but what would it be? Walking through Boston, he saw no shops offering soap or candles. He also observed that people didnt bathe very often. Families saved the fat they trimmed from meat and boiled it into tallow once a year - using most of it to make candles that would enable them to read the Bible at night. In his new profession of tallow chandler, Josiahs hard, smelly work began with gathering fat from markets amid clouds of flies, hauling it home in a wheelbarrow, and boiling it in wooden vats. The Franklin house was filled with a perpetual rancid stench.

After giving birth to seven children in eleven years, Anne Franklin died. Josiah took little time finding a new wife, dark-haired Abiah Folger from Nantucket, who was visiting her sister when Josiah met her in church. They married within weeks of Anne Franklins death and had ten children.

Benjamins first images of life were of the small rented house on Milk Street, then the oldest and poorest part of Boston, where Abiah nursed all her brood. My mother had an excellent constitution, Benjamin wrote in his autobiography. She suckled all her children. There was scarcely a time Abiah did not have a baby at breast as she spun, wove cloth, sewed, cooked, cleaned, kept her husbands accounts, sang hymns, and taught the children their prayers.

After the drowning of Benjamins sixteen-month-old brother in an unattended tub of soaping water, Josiah bought a larger house in Bostons commercial district and set up his tallow business in a separate building. His business was growing, and he was elected to a series of minor town offices. Despite the fact that Josiah prayed over, preached at, beat, berated, neglected, pampered, and menaced his children, the Franklin family still enjoyed what the youngest, Jane, remembered as a good, although austere, life: It was indeed a lowly dwelling we were brought up in but we were fed plentifully, made comfortable with fire and clothing, had seldom any contention among us.

Benjamins father rose up through the Puritan church ranks, eventually becoming a tithing-man, his job to enforce church discipline over a quarter of the families in Boston. When not checking on the conduct of apprentice boys and servant girls, he would march down the aisle on the Sabbath to poke with his staff of office anyone nodding off or whispering. The Franklin family attended two church services on Sundays and religious lectures on Thursday afternoons, conducted family prayers morning and evening, and said grace over meals.

Once Benjamin Franklin left his fathers house, he never again joined a church and rarely attended one.

Josiahs children did all they could to avoid his wrath. Benjamins childhood was an unremitting struggle under so much restraint that it finally made all but inevitable his self-imposed exile from his family - and it forever soured him on religion. Once he left his fathers house, he never again joined a church and rarely attended one.

At age eight, Benjamin trudged off to the Boston Grammar School. He studied Latin and Greek until he could translate Aesops Fables into Latin verse, which is much harder than translating Latin into English. By the end of the year, he had overtaken pupils who started a year before him, and he moved to the head of his class. But then Josiah yanked him out of school: He had decided his son shouldnt be a clergyman after all, but should learn a useful trade.

Whenever he could, Benjamin began to slip down to the docks. His father placed him in an inexpensive school where he failed mathematics. He lost interest in his education, became aggressive, and began to settle arguments with his fists. He longed ship off to sea, but realizing he was too young, he taught himself to swim, rigged a kite, and used the wind to tow him, naked, across a pond.

By 1718, twelve-year-old Benjamin was the only son left at home. It didnt occur to Josiah, or other fathers of his generation, to ask the boy what he wanted to do. It was a matter of money. Josiahs nephew had just opened a cutlery shop. There would always be dull blades, but the cutler wanted his uncle to pay the usual apprenticeship fee and Josiah refused.

He took the boy to his older son, James, a printer. Benjamin would be his brothers apprentice and bound servant for the next nine years.

Speaking to his own son years later, Benjamin recounted the feeling of being imprisoned: I was to serve as an apprentice till I was twenty-one years of age. His brother quickly made it clear that Benjamin would receive no special favors. If he complained, he would be beaten. After a few sound thrashings, Benjamin was convinced.

Between 1719 and 1723, four years in which James humiliated him, he remained indomitably proud, always looking to increase his knowledge and to flaunt it. Bostons only public library had burned, so he talked his way into the Reverend Cotton Mathers great personal library. Another friend, a booksellers apprentice, slipped him new books at night on condition he return them unharmed the next morning before opening time. To steal hours for reading, he skipped church.

Benjamin quickly learned the printers trade, and took up writing, mastering the then-fashionable art of satire. He used it in his Silence Dogood letters, written stealthily on Sundays when other fifteen-year-old Boston boys were in church, slipping the letters under the door of his brothers print shop before it opened on Mondays. Masterful parodies of popular London writings, the fourteen letters created a stir in Boston, making his brothers paper, the New-England Courant, controversial.

Benjamin was cockier than ever, especially after it was revealed that he, posing as a young bride, had written the impertinent critiques of the Puritan way of life. His brother saw profit in Benjamins ready pen. When a lighthouse keeper and his family drowned, Benjamin wrote a sentimental ballad. The Courant sold briskly. When Blackbeard the pirate died, more purple quatrains flowed. Benjamin showed off his verses to his parents but his father ridiculed his performances, telling him verse makers are generally beggars.

But Benjamins writing skill finally won his freedom. When the Courant chided officials of the Massachusetts General Court for the slowness of its reaction to marauding pirates, the court jailed James. It was left to seventeen-year-old Benjamin Franklin to publish the paper alone. He filled it with his own writings. When the authorities finally released James, it was with a court order to cease publication altogether. Cleverly, James interpreted the order to mean the paper could continue as long as it was published by someone else. Benjamin would become the publisher, but in name only. To legitimize the ruse, he signed a release on the back of Benjamins articles of apprenticeship.

Benjamin realized that James could never show the document in court unless he wanted to be arrested for contempt. But that ruling didnt reach beyond Massachusetts, so Benjamin decided to flee the Bay colony. With the help of a friend, he sold some books, stole aboard a ship, and lay hidden for three days while his family frantically searched for him. Sailing to New York and then hiking fifty miles across New Jersey, he would seldom return to Boston.

Next page