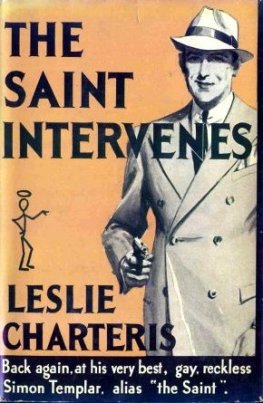

Leslie Charteris

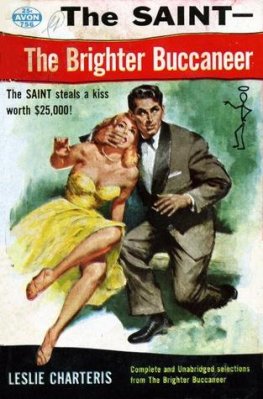

The Brighter Buccaneer

"Happy" Fred Jorman was a man with a grievance. He came to his partner with a tale of woe.

"It was an ordinary bit of business, Meyer. I met him in the Alexandra he seemed interested in horses, and he looked so lovely and innocent. When I told him about the special job I'd got for Newmarket that afternoon, and it came to suggesting he might like to put a bit on himself, I'd hardly got the words out of my mouth before he was pushing a tenner across the table. Well, after I'd been to the phone I told him he'd got a three-to-one winner, and he was so pleased he almost wept on my shoulder. And I paid him out in cash. That was thirty pounds thirty real pounds he had off me but I wasn't worrying. I could see I was going to clean him out. He was looking at the money I'd given him as if he was watching all his dreams come true. And that was when I bought him another drink and started telling him about the real big job of the day. 'It's honestly not right for me to be letting you in at all,' I said, 'but it gives me a lot of pleasure to see a young sport like you winning some money,' I said. 'This horse I'm talking about now,' I said, 'could go twice round the course while all the other crocks were just beginning to realize that the race had started; but I'll eat my hat if it starts at a fraction less than five to one,' I said."

"Well?"

"Well, the mug looked over his roll and said he'd only got about a hundred pounds, including what he'd won already, and that didn't seem enough to put on a five-to-one certainty. 'But if you'll excuse me a minute while I go to my bank, which is just around the corner,' he said, 'I'll give you five hundred pounds to put on for me.' And off he went to get the money "

"And never come back," said the smaller speaking part, with the air of a Senior Wrangler solving the first problem in a child's book of arithmetic.

"That's just it, Meyer," said Happy Fred aggrievedly. "He never came back. He stole thirty pounds off me, that's what it amounts to he ran away with the ground-bait I'd given him, and wasted the whole of my afternoon, not to mention all the brain work I'd put into spinning him the yarn "

"Brain work!" said Meyer.

Simon Templar would have given much to overhear that conversation. It was his one regret that he never had the additional pleasure of knowing exactly what his pigeons said when they woke up and found themselves bald.

Otherwise, he had very few complaints to make about the way his years of energetic life had treated him. "Do others as they would do you," was his motto; and for several years past he had carried out the injunction with a simple and unswerving wholeheartedness, to his own continual entertainment and profit. "There are," said the Saint, "less interesting ways of spending wet week-ends"

Certainly it was a wet week-end when he met Ruth Eden, though he happened to be driving home along that lonely stretch of the Windsor road after a strictly lawful occasion.

To her, at first, he was only the providential man in the glistening leather coat who came striding across from the big open Hirondel that had skidded to a standstill a few yards away. She had seen his lights whizzing up behind them, and had managed to put her foot through the window as he went past Mr. Julian Lamantia was too strong for her, and she was thoroughly frightened. The man in the leather coat twitched open the nearest door of the limousine and propped himself gracefully against it, with the broken glass crunching under his feet. His voice drawled pleasantly through the hissing rain.

"Evening, madam. This is Knight Errants Unlimited. Anything we can do?"

"If you're going towards London," said the girl quickly, "could you give me a lift?"

The man laughed. It was a short soft lilt of a laugh that somehow made the godsend of his arrival seem almost too good to be true.

An arm sheathed in wet sheepskin shot into the limousine and Mr. Lamantia shot out. The feat of muscular prestidigitation was performed so swiftly and slickly that she took a second or two to absorb the fact that it had indubitably eventuated and travelled on into the past tense. By which time Mr. Lamantia was picking himself up out of the mud, with the rain spotting the dry portions of his very natty check suit and his vocabulary functioning on full throttle.

He stated, amongst other matters, that he would teach the intruder to mind his own unmentionable business; and the intruder smiled almost lazily.

"We don't like you," said the intruder.

He ducked comfortably under the wild swing that Mr. Lamantia launched at him, collared the raving man below the hips, and hoisted him, kicking and struggling, onto one shoulder. In this manner they disappeared from view. Presently there was a loud splash from the river bank a few yards away, and the stranger returned alone.

"Can your friend swim?" he inquired interestedly.

The girl stepped out into the road, feeling rather at a loss for any suitable remark. Somewhere in the damp darkness Mr. Lamantia was demonstrating a fluency of discourse which proved that he was contriving to keep at least his mouth above water; and the conversational powers of her rescuer showed themselves to be, in their own way, equally superior to any awe of circumstances.

As he led her across to his own car he talked with a charming lack of embarrassment.

"Over on our left we have the island of Runnymede, where King John signed the Magna Carta in the year 1215. It is by virtue of this Great Charter that Englishmen have always enjoyed complete freedom to do everything that they are not forbidden to do"

The Hirondel was humming on towards London at a smooth seventy miles an hour before she was able to utter her thanks.

"I really was awfully relieved when you came along though I'm afraid you've lost me my job."

"Like that, was it?"

"I'm afraid so. If you happen to know a nice man who wants an efficient secretary for purely secretarial purposes, I could owe you even more than I do now."

It was extraordinarily easy to talk to him she was not quite sure why. In some subtle way he succeeded in weaving over her a fascination that was unique in her experience. Before they were in London she had outlined to him the whole story of her life. It was not until afterwards that she began to wonder how on earth she had ever been able to imagine that a perfect stranger could be interested in the recital of her inconsiderable affairs. For the tale she had to tell was very ordinary a simple sequence of family misfortunes which had forced her into a profession amongst whose employers the Lamantias are not so rare that any museum has yet thought it worth while to include a stuffed specimen in the catalogue of its exhibits.

"And then, when my father died, my mother seemed to go a bit funny, poor darling! Anyone with a get-rich-quick scheme could take money off her. She ended up by meeting a man who was selling some wonderful shares that were going to multiply their value by ten in a few months. She gave him everything we had left; and a week or two later we found that the shares weren't worth the paper they were printed on."

"And so you joined the world's workers?"

She laughed softly.

"The trouble is to make anyone believe I really want to work. I'm rather pretty, you know, when you see me properly. I seem to put ideas into middle-aged heads."

She was led on to tell him so much about herself that they had reached her address in Bloomsbury before she had remembered that she had not even asked him his name.

"Templar Simon Templar," he said gently.

She was in the act of fitting her key into the front door, and she was so startled that she turned around and stared at him, half doubtful whether she ought to laugh.