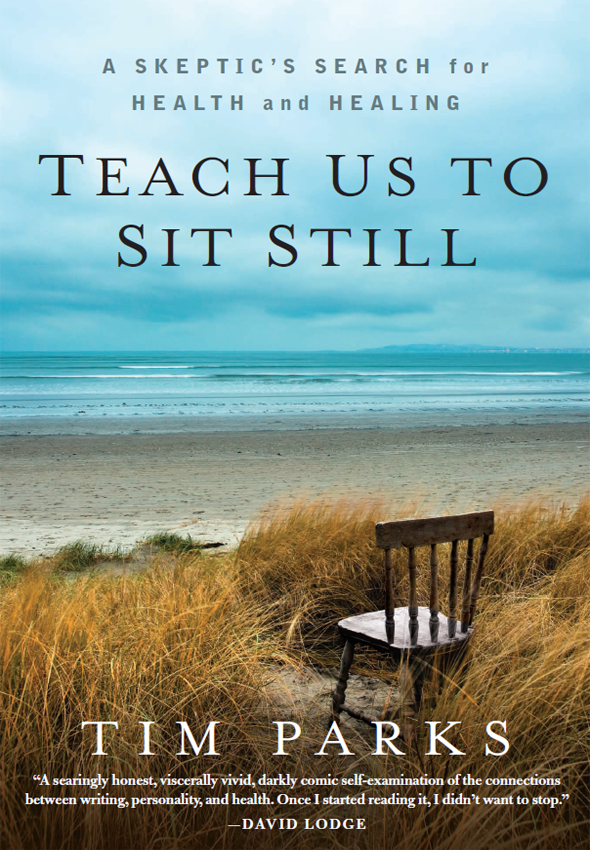

Praise for Teach Us to Sit Still

Tim Parkss account of curing his ill health through meditation is intensely engaging.

The Sunday Times

Even those free of illness will find Parkss journey gives us much to ponder about the effects of modern living.

Metro

A wonderful, paradoxical book.

The Guardian

Parks writes wonderfully well about his body as he is reluctantly reconciled to its existence alongside his mind.

DailyExpress

Also by Tim Parks

FICTION

Tongues of Flame

Loving Roger

Home Thoughts

Family Planning

Goodness

Cara Massimina

Mimis Ghost

Shear

Europa

Destiny

Judge Savage

Rapids

Cleaver

Dreams of Rivers and Seas

NONFICTION

Italian Neighbours

An Italian Education

Adultery & Other Diversions

Translating Style

Hell and Back

A Season with Verona

The Fighter

To those who got me out of jail:

David Wise and Rodney Anderson;

Ruggero Scolari, Edoardo Parisi, John Coleman

Authors Note

O ver the period when I wasnt well, and again when I was writing this book, I found myself spending more and more time looking at images. It began with a need for clarity, the desire to see my physical problem represented, but more and more the contemplation of images of any kindillustrations, photos, paintingsseemed to offer relief from the language-driven anxieties inside my head. Eventually I decided to include some of these pictures in the book; not all of them are beautiful, not all of them are of the highest quality; they had simply become part of the tale.

Foreword

I never expected to write a book about the body. Least of all my body. How indiscreet. But then I never expected to be ill in the mysterious, infuriating way I have. Above all it never occurred to me that an illness might challenge my deepest assumptions, oblige me to rethink the primacy I have always given to language and the life of the mind. Texting, mailing, chatting, blogging, our modern minds devour our flesh. That is the conclusion long illness brought me to. We have become cerebral vampires preying on our own lifeblood. Even in the gym, or out running, our lives are all in the head, at the expense of our bodies.

I had no desire to tell anyone about my malady, let alone write about it. These were precisely the pains and humiliations one learns early on not to mention. You need only look at the words medicine usesintestine, feces, urethra, bladder, sphincter, prostateto appreciate that this vocabulary was never meant to be spoken in company. We just dont want to go there. My plan, like anyone elses, was to confide in the doctors and pretend it wasnt happening.

On the other hand, this is reality, and in my case there was the happy truth that just when the medical profession had given up on me and I on it, just when I seemed to be walled up in a life sentence of chronic pain, someone proposed a bizarre way out: sit still, they said, and breathe. I sat still. I breathed. It seemed a tedious exercise at first, rather painful, not immediately effective. Eventually it proved so exciting, so transforming, physically and mentally, that I began to think my illness had been a stroke of luck. If I wasnt the greatest of skeptics, Id be saying it had been sent from above to invite me to change my ways. In any event, by now the story had become too inviting a conundrum to be left unwritten.

What it boils down to, I suppose, is an extraordinary mismatch between the creatures we are and the way we live. I grew up in a family of evangelical Anglicans. They were also solid middle-class Brits. What they most instilled in us, as children, was purposefulness, urgency. Everything about the world had long been understood, so the right moves were obvious. We must save our souls, we must save other souls, we must perform well at school, we must go to university and get good jobs. And we must marry and have children who would share our same goals and live as we did. Even singing was purposeful. It was to praise God. Playing, we were soldiers bent on killing each other, in a good cause. When we did sports, of course, we had to win.

Meantime our bodies were the vessels that allowed us to get on with all these pressing tasks. Confusingly, a vessel was a ship or a jug for storing liquids. Either way it was useful only insofar as it contained something else: the Christian soul, the middle-class self. In any event, the body had no purpose or identity as such. When we were dead we would be better off without it, though for reasons not explained God wanted us to hang on with bodily grief for as long as we could. Perhaps it was to purify the soul, to ennoble the self, the way some people find a sort of virtue in hanging on to an old car. The body was a necessary hassle on the way to success and paradise.

This will sound like a caricature. But it was entirely in line with school biology, where they merely told us how complicated and alien that fleshly vessel was, a matter best left to the experts. Even today I meet few people who accept a substantial identity between self and flesh. At most, they have a more attractive vision of what pleasures and enjoyments life affords: sex, food, music, booze. Other wise, everyone seems equally busy asserting their points of view, furthering their careers, saving against the day when the decaying vessel will start to leak. In the main, doing cancels out being as noise swamps silence.

To date I have written twenty books, with this twenty-one. I may have shaken off my parents faith, then, but not the unrelenting purposefulness they taught me, that heady mix of piety and ambition. And like my father I have lived under a spell of words. He read the Bible and wrote his sermons. He told you what was true and how you must behave. Rhythmically, persuasively, the way politicians do, and the pundits of opinion columns; the people who know everything and are sure of themselves. My novels have tended the other way, suggested how mysterious it all is, how partial anyones point of view, how comically lost we are. But even this is preaching of a kind. The fact is, as soon as you start with words youre locked into a debate, forced to take a position with respect to others, confirming or rebutting what has been said before. Nothing you say stands alone or is complete in the present: it has its roots in the past and pushes feelers into the future. And as we grow heated, marking out our corner, staking our claim, we stop noticing the breath on the lips, the tension in our fingers, the pressure of the ground under our toes, the tick of time in the blood. None of my fathers admirers noticed how tense his jaw was, how much his hand shook when he raised a glass or microphone, what an effort it was for him to assert, assert, assert, to keep the 2,000-year-old faith, giving encouragement to the doubters, finding clever arguments to confound the devils advocates. When I think back on Dads cancer and deathhe was sixty and I twenty-fivethere is a certain inevitability about it. Forever ignored, the carnal vessel cracked under strain. Sometimes I think it was the invention of language that started this queer battle between mind and flesh.

Shortly after Dads funeral, I left England for Italy and have lived here ever since. The illusion of escape was reassuring. Another language plunged me into other debates. I worked and worked. I wrote and translated and taught. But in retrospect I see I never really deviated from the initial project, never looked to right or left, was always true to my parents obsession with vocation. Your hand writing, I remember my brother observing, in those last years when one wrote letters by hand, has never changed. He was right. Its still the same: ferociously slanted to somewhere off the page, some distant goal.

Next page