CONTENTS

ABOUT THE BOOK

His name was Antonio, but they would call him Nem. From the infamous favela of Rocinha in Rio, he was a hardworking young father forced to make a decision that would turn his world upside down.

Nemesis is the story of an ordinary man who became the king of the largest slum in Rio, the head of a drug cartel and perhaps Brazils most wanted criminal. A man who tried to bring welfare and justice to a playground of gang culture and destitution, while everyone around him drew guns and partied. Its a gripping tale of gold-hunters and evangelical pastors, bent police and rich-kid addicts, quixotic politicians and drug lords with maths degrees.

Traversing through rainforests and high-security prisons, filthy slums and glittering shopping malls, this is also the story of how change came to Brazil. Of a countrys journey into the global spotlight, and the battle for the beautiful but damned city of Rio, as it struggles to break free from a tangled web of corruption, violence, drugs and poverty. With Nem at its centre, locked in a fight for his countrys soul.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Misha Glenny is a distinguished investigative journalist and historian. As the Central Europe Correspondent first for the Guardian and then for the BBC, he chronicled the collapse of communism and the wars in the former Yugoslavia. He has won several major awards for his work, including the Sony Gold Award for outstanding contribution to broadcasting and is the author of five books. These include the acclaimed McMafia, which was shortlisted for the FT Business Book of the Year, and DarkMarket, which was shortlisted for The Orwell Prize.

In the recent past, he has divided his time between Brazil and London, living for several months in Rocinha, the favela at the heart of this story.

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

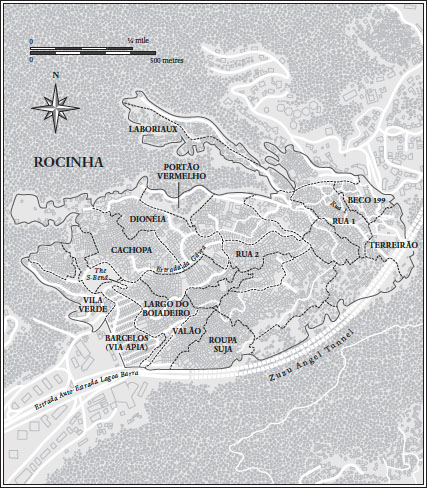

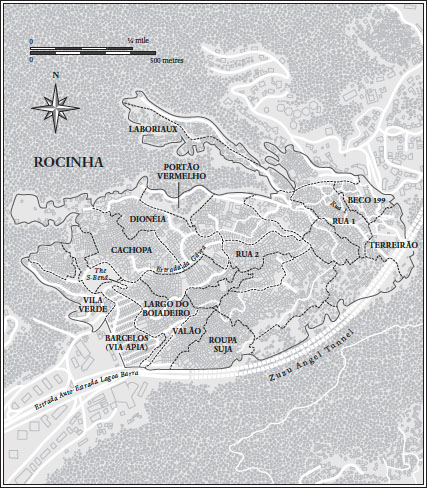

Rocinha

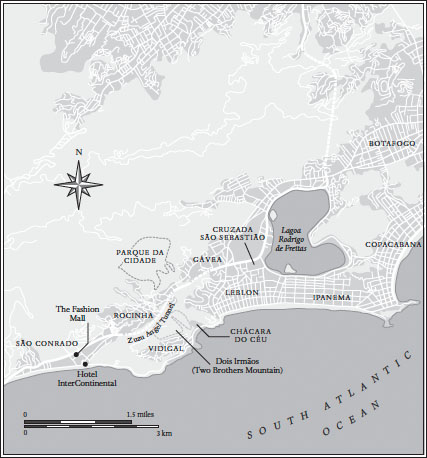

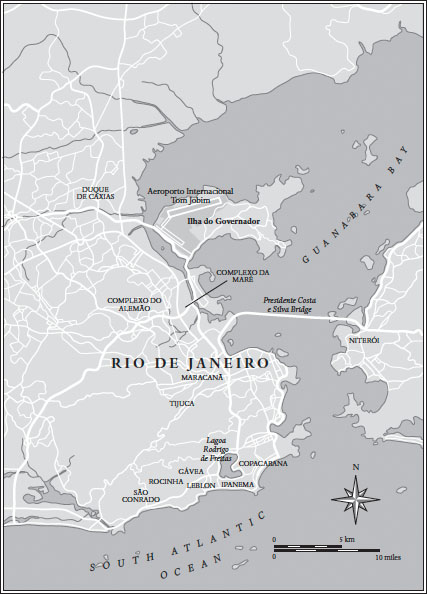

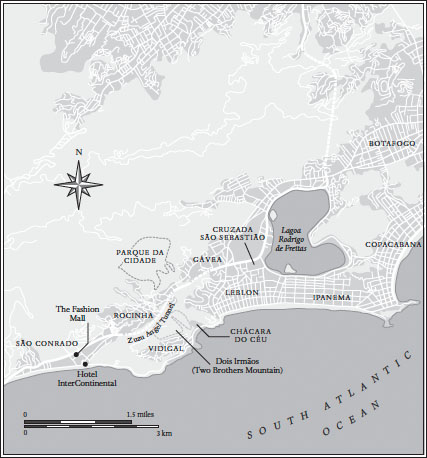

The South Zone

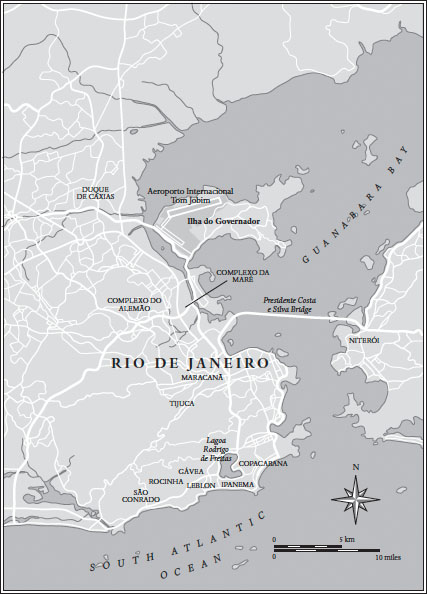

Rio de Janeiro

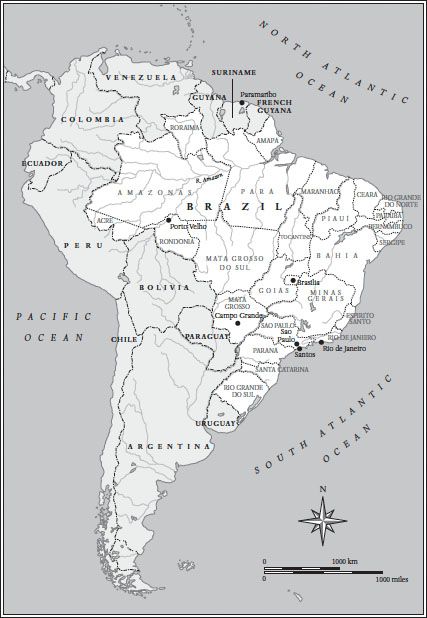

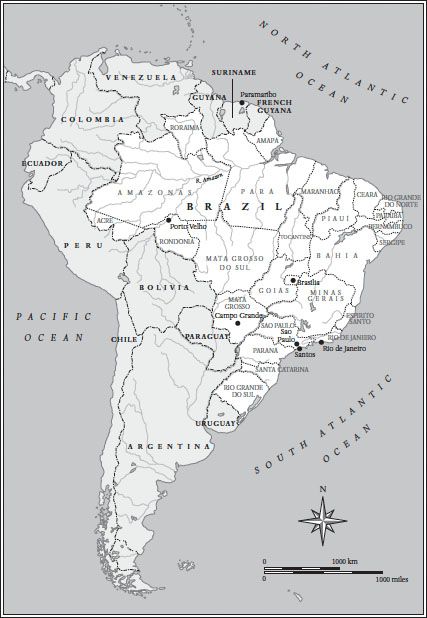

Brazil

In Memoriam

Sasha Glenny

19922014

Nemesis

One Man And The Battle For Rio

Misha Glenny

Brazil, this beautiful country, has the worlds ugliest record. We are the number one champion in homicidal violence. One in every ten people killed around the world is a Brazilian. This translates into over 56,000 people dying violently each year. Most of them are young black boys, dying by guns. Brazil is also one of the worlds largest consumers of drugs and the War on Drugs has been especially painful here. Around 50% of the homicides on the streets of Brazil are related to the War on Drugs.

Ilona Szab de Carvalho, Igarap Institute, TED Talk,

October 2014, Rio de Janeiro

PREFACE

LANDING IN CAMPO Grande for the first time was a strange experience. The capital of Mato Grosso do Sul is located some 250 miles east of the point where Brazil, Paraguay and Bolivia meet. It is also roughly the same distance south of the Pantanal, the worlds largest tropical wetland. My first impression was that it barely felt like Brazil at all.

Only just over a century old, Campo Grande was built on a grid system, its wide boulevards and cross streets lined by plentiful trees. I was struck by the number of shops with large long windows. Butchers displayed literally dozens of lean cattle carcasses. A John Deere store boasted row upon row of tractors. It felt more like rural Texas in the 1960s than sensual Rio de Janeiro or industrious So Paulo.

At the starkly defined limits of the city, spacious buildings suddenly gave way to soil so vermilion it looked as though the ground had been painted. The contrast with the deep green of the vegetation turned the entire area into a cartoon landscape.

Just at the point where everything became red and green, I took an unsigned turn off the ring road. I had to dodge some oil barrels placed on a dirt track before reaching a wire-mesh gate. From here, most of the maximum security federal penitentiary was visible. I was immediately struck by the crisp and modern design of its walls and watchtowers. The buildings were finished in gentle pastel red and yellow.

After the first gate opened automatically, I had to negotiate one final obstacle tank traps. Brazil has a rich tradition of prison breakouts, and Campo Grande was taking no chances. One of four special facilities dotted around this enormous country, the jail was built for those criminals deemed the most dangerous. Campo Grande does not resemble Brazils more famous cities, and this jail is unlike most of its prisons.

Firstly, the prison guards were unfailingly friendly and polite. Some spoke quite good English, an uncommon skill in Brazils interior. Within the constraints of their job, they all went out of their way to assist me.

There was no evidence of the squalor, overcrowding and latent violence associated with much of the prison system. The Campo Grande facility has an air of order and predictability. It is not an easy regime for the inmates, but there are no reports of human rights abuses and no complaints about arbitrary violence. Not a single prisoner in the four facilities has ever been the subject of a murderous attack by his fellow detainees, nor has there ever been a successful breakout. In most other Brazilian prisons these hazards are commonplace.

The notoriety of the prisoners is the chief reason for the jails unusually efficient administration. In the past, the great bank robbers and drug cartel leaders would happily continue their work after incarceration from inside prison. In the provincial and municipal facilities it is standard practice to bribe the poorly remunerated guards to turn a blind eye to smuggled cell phones, to drugs, to video game consoles and televisions, or to women brought in for sex.

In Campo Grande, the only way the inmates can get messages to the outside world apart from letters, which are strictly monitored, is through their lawyers or those members of their family who have permission to visit. This represents a challenge even for the best-organised criminals.

After placing my personal effects in a locker, I was taken through a series of security screenings and biometric checks. I was allowed to keep my watch, my glasses and, by special permission of the courts, a digital voice recorder, but absolutely nothing else. These were checked and checked again before two federal officers led me into a rectangular room about 10 feet by 20.

To the left was a desk with a computer and a video camera on it. The wall to the right was covered by a backdrop with the words Federal Department of Prisons writ large. The room was used by prisoners appearing via video link to wherever their trial was being held Rio de Janeiro, So Paulo, Manaus or Recife.

Opposite me sat the man I had come to visit Antnio Francisco Bonfim Lopes. Until his arrest in November 2011, he had been the most wanted man in Rio de Janeiro, if not in all Brazil. The country knew him not by his birth name, but by his nickname, Nem, or, in its entire Brazilian Portuguese version, O Nem da Rocinha Nem of Rocinha.

Next page