The Twenty-Seventh City

by

Jonathan Franzen

This story is set in a year somewhat like 1984 and in a place very much like St. Louis. Many actual public achievements, policies and products have been attributed to various characters and groups; these should not be confused with any actual person or organization. The lives and opinions of the characters are entirely imaginary.

Praise for the Twenty-Seventh City

Unsettling and visionaryThe Twenty-Seventh City is not a novel that can be quickly dismissed or easily forgotten: it has elements of both Great and American.A book of memorable characters, surprising situations, and provocative ideas.

Michele Slung, The Washington Post

Franzens tour de force (to call it a first novel is to do it an injustice) is a sinister fun-house-mirror reflection of urban America in the 1980s. Theres a lot of reality out there. The Twenty-Seventh City, in its larger-than-life way, is a brave and exhilarating attempt to master it.

Michael Upchurch, The Seattle Times

Franzen goes for broke here hes out to expose the soul of a city and all the bloody details of the way we live. Franzen has written a book of range, pith, intelligence.

Margo Jefferson, Vogue

A weird hybrid of realism and fantasy: municipal science fiction. Everything proceeds from a daring, outrageously unlikely premise.

Terrence Rafferty, The New Yorker

Mr. Franzen has proved with this immodestly ambitious first novel that he has talent to spare. His is a worthwhile entertainment, this picaresque tale the principal vagabond of which is its own sinuous plot.

Donna Rifkind, The Wall Street Journal

He has the kind of ability that can take what one would have thought the most mundane of cities and render it as an utterly persuasive labyrinth of mystery and meaning.

Mark Feeney, The Boston Sunday Globe

An imaginative and riveting examination of our flawed society. The Twenty-Seventh City provides a rare blend of entertainment and profound social commentary.

Christine Vogel, Chicago Sun-Times

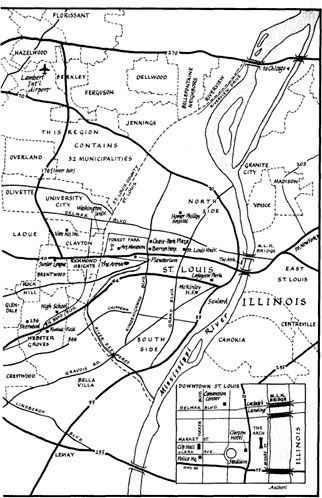

In early June Chief William OConnell of the St. Louis Police Department announced his retirement, and the Board of Police Commissioners, passing over the favored candidates of the city political establishment, the black community, the press, the Officers Association and the Missouri governor, selected a woman, formerly with the police in Bombay, India, to begin a five-year term as chief. The city was appalled, but the woman one S. Jammu assumed the post before anyone could stop her.

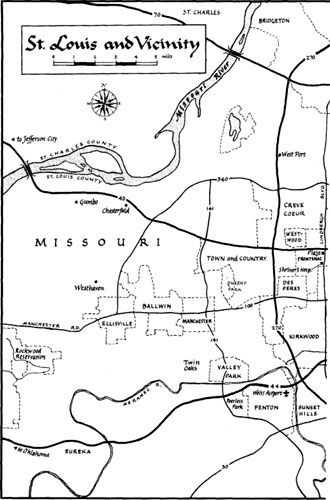

This was on August 1. On August 4, the Subcontinent again made the local news when the most eligible bachelor in St. Louis married a princess from Bombay. The groom was Sidney Hammaker, president of the Hammaker Brewing Company, the citys flagship industry. The bride was rumored to be fabulously wealthy. Newspaper accounts of the wedding confirmed reports that she owned a diamond pendant insured for $11 million, and that she had brought a retinue of eighteen servants to staff the Hammaker estate in suburban Ladue. A fireworks display at the wedding reception rained cinders on lawns up to a mile away.

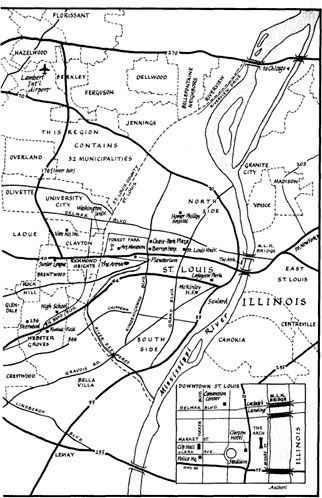

A week later the sightings began. An Indian family of ten was seen standing on a traffic island one block east of the Cervantes Convention Center. The women wore saris, the men dark business suits, the children gym shorts and T-shirts. All of them wore expressions of controlled annoyance.

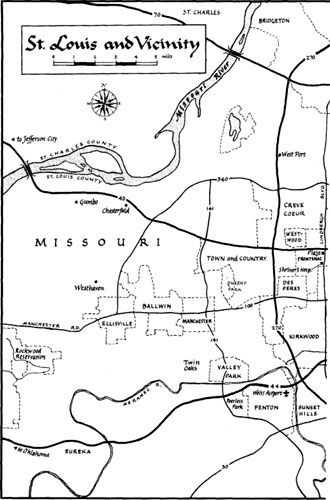

By the beginning of September, scenes like this had become a fixture of daily life in the city. Indians were noticed lounging with no evident purpose on the skybridge between Dillards and the St. Louis Centre. They were observed spreading blankets in the art museum parking lot and preparing a hot lunch on a Primus stove, playing card games on the sidewalk in front of the National Bowling Hall of Fame, viewing houses for sale in Kirkwood and Sunset Hills, taking snapshots outside the Amtrak station downtown, and clustering around the raised hood of a Delta 88 stalled on the Forest Park Parkway. The children invariably appeared well behaved.

Early autumn was also the season of another, more familiar Eastern visitor to St. Louis, the Veiled Prophet of Khorassan. A group of businessmen had conjured up the Prophet in the nineteenth century to help raise funds for worthy causes. Each year He returned and incarnated Himself in a different leading citizen whose identity was always a closely guarded secret, and with His non-denominational mysteries He brought a playful glamour to the city. It had been written:

There on that throne, to which the blind belief

Of millions raisd him, sat the Prophet-Chief,

The Great Mokanna. Oer his features bung

The Veil, the Silver Veil, which he had flung

In mercy there, to hide from mortal sight

His dazzling brow, till man could bear its light.

It rained only once in September, on the day of the Veiled Prophet Parade. Water streamed down the tuba bells in the marching bands, and trumpeters experienced difficulties with their embouchure. Pom-poms wilted, staining the girls hands with dye, which they smeared on their foreheads when they pushed back their hair. Several of the floats sank.

On the night of the Veiled Prophet Ball, the years premier society event, high winds knocked down power lines all over the city. In the Khorassan Room of the Chase-Park Plaza Hotel, the debbing had just concluded when the lights went out. Waiters rushed in with candelabras, and when the first of them were lit the ballroom filled with murmurs of surprise and consternation: the Prophets throne was empty.

On Kingshighway a black Ferrari 275 was speeding past the windowless supermarkets and fortified churches of the citys north side. Observers might have glimpsed a snow-white robe behind the windshield, a crown on the passenger seat. The Prophet was driving to the airport. Parking in a fire lane, He dashed into the lobby of the Marriott Hotel.

You got some kind of problem there? a bellhop said.

Im the Veiled Prophet, twit.

On the top floor of the hotel He stopped outside a door and knocked. The door was opened by a tall dark woman in a jogging suit. She was very pretty. She burst out laughing.

* * *

When the sky began to lighten, low in the east over southern Illinois, the birds were the first to know it. Along the riverfront and in all the downtown parks and plazas, the trees began to chirp and rustle. It was the first Monday morning in October. The birds downtown were waking up.

North of the business district, where the poorest people lived, an early morning breeze carried smells of used liquor and unnatural perspiration out of alleyways where nothing moved; a slamming door was heard for blocks around. In the railyards of the citys central basin, amid the buzzing of faulty chargers and the sudden ghostly shiverings of Cyclone fences, men with flattops dozed in square-headed towers while rolling stock regrouped below them. Three-star hotels and private hospitals with an abject visibility occupied the higher ground. Farther west, the land grew hilly and healthier trees knit the settlements together, but this was not St. Louis anymore, it was suburb. On the south side there were rows upon rows of cubical brick houses where widows and widowers lay in beds and the blinds in the windows, lowered in a different era, would not be raised all day.

Next page