| Enigmas of Identity

Enigmas of Identity | Peter Brooks

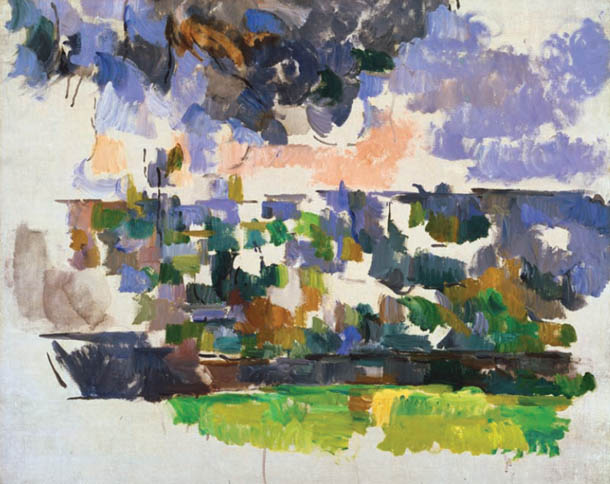

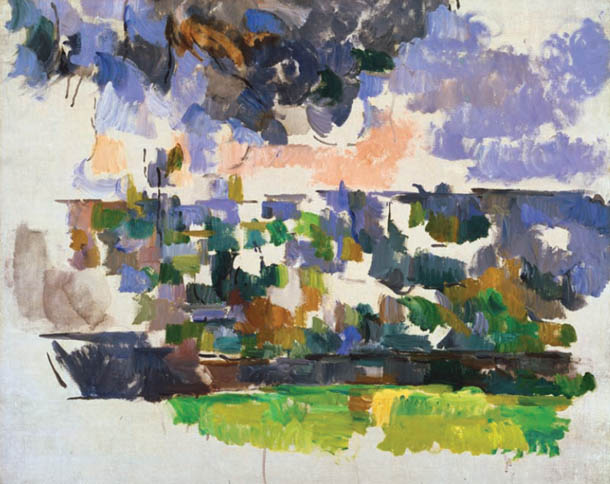

Frontispiece and jacket. Paul Czanne, The Garden at Les Lauves (Le Jardin des Lauves), c. 1906. Oil on canvas, 25-3/4 31-7/8 in. (65.405 80.9625 cm.). Acquired 1955. Courtesy of The Phillips Collection, Washington, D.C.

Copyright 2011 by Princeton University Press

Requests for permission to reproduce material from this work

should be sent to Permissions, Princeton University Press

Published by Princeton University Press, 41 William Street,

Princeton, New Jersey 08540

In the United Kingdom: Princeton University Press, 6 Oxford Street,

Woodstock, Oxfordshire OX20 1TW

press.princeton.edu

All Rights Reserved

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Brooks, Peter, 1938

Enigmas of identity / Peter Brooks.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-691-15158-8 (hardcover : alk. paper) 1. Group identity.

I. Title.

HM753.B76 2011

305dc22 2011005722

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available

This book has been composed in Garamond Premier Pro

Printed on acid-free paper.

Printed in the United States of America

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

| Contents

| Enigmas of Identity

| To Begin

Take a nightmare situation evoked by Jean-Paul Sartre to image his childhood sense that he was a fraud, lacking all authenticity. He has sneaked onto a train from Paris to Dijon and fallen asleep, and when the conductor comes to ask for his ticket, he has to admit he doesnt have one. Nor the money to pay for one. Yet he makes the grandiose claim that he needs to be in Dijon for important and secret reasons, reasons that concerned France and perhaps all mankind. This scenarioin which the conductor remained mute, unconvinced, and the boy talked on and oncould never reach an ending. The higher callingthe salvation of mankindremained an apology for his ticketless train trip, but not one he could really explain. Somehow the train ride had to continue, but without any certain point of arrivalor justification.

Such, we might say, is life, or at least our sense of personal identity within the world, at once unjustified and, to us, crucially important. That is more or less the question I want to work toward in this book. It was not quite my starting point; it took me some time to understand that identity was the concept I was after. In essence, the book had its inception in a course I taught under the title Character, Person, Identity. I was interested in the fact that character, so central to our experience of reading novels (or biographies, or watching plays, or voting for elected officials) was very hard to talk about. Character has never been given the kind of systematic analysis that other elements of storytelling have received, such as plot or point of view or reader response: it isnt susceptible to formal analysis in the same way. There have been fine books on character, notably Alex Wolochs The One vs. the Many, which demonstrates the structural importance of minor characters for the emergence of the protagonist. But the concept (as Woloch and other commentators are aware) stretches beyond any formal definition to encompass much of what we want to include when we speak about persons, the second term in my trilogy, as entire human beings.

Its fairly easy to talk about person in a minimalist wayas a grammatical person in, for instance, the pronouns I or you or sheand in that manner begin to understand at least the structured role of persons as participants in a conversation. The analysis of the ways in which language understands persons can be rigorous, and helpfulbut it does not resolve all the issues we want to talk about with character. I couldnt find any minimal position in regard to person in our fuller understanding of personhood, individuality. As with character, so with person in this larger sense: I couldnt find the terms for an analytic discussion. Character slops over into all our discussions of ethics and morality. Where we now talk of writing a recommendation for someone, for instance, our forebears used to speak of giving someone a character: doing what was still earlier called his or her moral portrait. That was in ages that perhaps believed in character as a more definitive and complete conception than we do now. Sigmund Freud and others have seemingly shattered the unitary notion of characterthough reading the great nineteenth-century novelists one perceives that they never subscribed to the closed, complete, self-contained, harmonious notion of character or person that we at times ascribe to the Victorians, and which was ostensibly their goal in education and child rearing.

Character in fact turned out to be beyond my powers of systematic analysis. Not that one has to bring systematic analysis to the concept, which remains useful precisely because of its semantic range, which starts from writing, inscription; the first meaning recorded in the Oxford English Dictionary has to do with engravings on coins: a distinctive mark impressed, engraved, or otherwise formed; a brand, stamp. Already this original meaning has a figural extension: by characters graven on thy brows... , the OED gives us, in a quotation from Christopher Marlowes Tamburlaine (1586). And what is engraved on your brows should ethically correspond to what is in your heart. By the eleventh definition, we have the sum of the moral and mental qualities which distinguish an individual or a race, viewed as a homogeneous whole; the individuality impressed by nature and habit on a man or nation; mental or moral constitution. That gets it all in, the better and the worse ways in which character has been conceived. By the time we reach definition seventeen, the concept has moved into literature: a personality invested with distinctive attributes and qualities, by a novelist or dramatist; also, the personality or part assumed by an actor on the stagewith a reference here to Henry Fieldings Tom Jones (1749). All our aesthetics and our ethics converge in character, in what Aristotle referred to as ethosas opposed to mythos, story or plot.

So character was too broad and slippery, whereas person was either too narrow, with too much of a grammatical presupposition, or else as replete and elusive as character. What about identity? It dawned on me that questions of character in the modern novelsay, from the time of Tom Jones onvery often posed themselves as problems of identity. Tom Jones is a foundling who will eventually be revealed as the natural son of Squire Allworthys sister. That kind of identity is common in the eighteenth-century novel: a disposition to act nobly eventually is underwritten and explained by gentlemanly parentage. The nineteenth-century novel also is full of foundlings, orphans doomed to live with abusive stepparents. But it is less common for them to stand revealed at the end as nobly born. They are much more apt to have to forge their own identities. Who you arein the sense of what you can legitimately call yourself, and what others call youseems to have become a problem with entry into the modern age in a way that it wasnt before. There are exemplary cases in Charles DickensPip of Great Expectations may be the most striking, since he begins his story by naming himself Pip, and recording this act in the graveyard where headstones mark his dead parentsand in Emily and Charlotte Bront, and in many others. Orphan status gives one the opportunity for self-definition, including the selection of an ideal parentor someone taken to be suchthat will be so important not only to Pip but to Honor de Balzacs ambitious young men Eugne de Rastignac and Lucien Chardon de Rubempr, for instance.

Next page