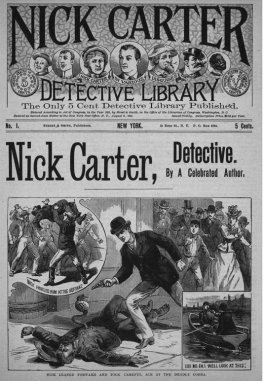

Nick Carter, Detective: The Solution of a Remarkable Case

CHAPTER I.

THE MURDER IN FORTY-SEVENTH STREET.

The city of New York was electrified one evening by the news that one of its greatest favorites had been foully murdered.

Eugenie La Verde had been found dead in her room and the murderer had not left a single clew, however slight, by which he could be traced.

Mademoiselle La Verde had been before the public for two seasons as a danseuse, and by her remarkable beauty and modesty, as well as by the unparalleled grace with which she executed her inimitable steps she had won her way to the hearts of all.

On the evening preceding her death she had danced as usual, winning round after round of applause, and a deluge of flowers.

Immediately after the performance she had been driven to her home in Forty-seventh street, accompanied only by her maid, who had been with her for many years, and who scarcely ever left her presence.

The maid had attended her as usual that night; had remained with her until she had disrobed, and then, at her mistress' request, had given her a book, and retired.

Eugenie had bade her servant good-night as usual, adding the injunction that she did not wish to be disturbed before ten o'clock on the following morning.

At ten o'clock precisely on the morning of the succeeding day, the maid, whose name was Delia Dent, had gone to her mistress' room to assist her in dressing, and upon entering, had been so horrified by the sight that met her gaze that she had swooned away then and there.

Eugenie La Verde was lying upon her bed, clad in the soft wrapper which the maid had helped her to don before leaving her on the preceding night.

Her face was distorted and swollen almost beyond recognition, and in spots was highly discolored, where the blood had coagulated beneath the skin. Her mouth was open, and her eyes were wide and staring, even yet filled with an expression of the horror through which she had passed just before her death. Her delicate hands, pretty enough for an artist's model, were clenched until the finger-nails had sunk into the tender flesh and drawn blood. The figure bore every evidence of a wild and terrific Struggle to escape from the grasp in which she had been seized, while the dull blue mark around her throat told only too plainly how her death had been accomplished.

The bed bore every evidence of a wild and terrific struggle. The coverings were tumbled in great confusion, one pillow had fallen upon the floor, and the book which the murdered girl had been engaged in reading when the grip of the assassin had seized her, was torn and crumpled.

Eugenie was dead, and everything in the room bore mute evidence that she had died horribly, and that she had struggled desperately to free herself from the attack of her slayer.

In searching for evidence of the presence of the murderer, not a clew of any kind could be found.

How he had gained access to the room where the danseuse was reading, or how he had left it after consummating the horrible deed, were mysteries which the keenest detectives failed to fathom

Theories were as plenty as mosquitoes in June, but there was positively no proof in support of any of, them, and one by one they fell to the ground and were abandoned as useless or absurd.

As a last resort, Delia Dent, the maid, fell under the ban of suspicion. But only for a time. The most stupid of investigators could not long believe her guilty of a crime so heinous, while, moreover, it was certain that she was not possessed of the necessary physical strength to accomplish the deed.

Neither had she the will power, for beyond her love for her dead mistress, the woman was weak and yielding in her nature.

Delia Dent did not long survive her mistress.

The terrible shock caused by the discovery of Eugenie's dead body was more than her frail strength could bear. She was prostrated nervously, and after growing steadily worse for a period of four weeks, she died at the hospital where she had been taken.

One theory, which for a time found many supporters, was that Delia Dent had been in league with the murderer; had admitted him to the house, and had allowed him quietly to depart after the deed was done.

But that theory was also abandoned, as being even more absurd than the others that had been advanced. Delia was conscious to the last, during her sickness, at the hospital, and just before her death she devised all her savings-a sum amounting to nearly ten thousand dollars-to her lawyer, in trust for the person who should succeed in bringing the murderer of Eugenie La Verde to justice. The house in Forty-seventh street, where Eugenie had been killed, was, at the time, occupied solely by herself and the maid Delia, and the basement was never used by them at all. Once a month the man who examined the gas-meter came to attend to his duty, and upon such occasions he passed through the basement hall on his way to the cellar. But when his work was done, Delia always locked and chained the door which communicated between the basement and the parlor floor, and it was never again disturbed until the same necessity arose during the following month.

Eugenie never dined at home, and her maid never left her. Her breakfast, which consisted only of coffee and a roll, was always prepared by the maid over an alcoholic lamp in the room where Eugenie slept.

After the discovery of the crime, a careful examination was made of every window and door in the house which communicated by any possibility with the outside world.

All were found securely locked, and every door was provided with the additional security afforded by a chain.

Even the scuttle had an intricate padlock:

Nothing had been molested.

Window-fastenings, door-locks, chain-bolts, scuttle and sky-light were alike undisturbed.

From the circumstances of the case as they were discovered after the commission of the crime, it was absolutely impossible for the murderer to have gained access to the house without leaving some evidence of the fact. Again, supposing the assassin to have been already concealed therein, it was equally impossible that he could have gotten out without furnishing some clew.

Delia Dent, as has been said, had fainted when she discovered the dead body of her young mistress. Upon reviving, she had staggered to a messenger call in the hallway, having barely strength to ring for the police. Then, still half-fainting, she had managed to reach the foot of the stairs, but had not yet unchained the front door when her call was answered. She believed that she fainted twice, or that site was in a state of semi-consciousness during the interval that elapsed between the discovery of the crime and the arrival of the police.

The more thorough the investigation, the deeper grew the mystery.

Old and tried detectives were put upon the case. At first they looked wise and assured everybody of the speedy apprehension of the fiend who had committed the deed. Then they became puzzled, and finally utterly confounded. The bravest of them at last confessed that they were no nearer the truth than at the beginning, and one of them, the shrewdest of all, boldly stated that the only way in which the assassin would ever be discovered would be by his voluntary confession, which was not likely to ensue.

Thus matters drifted on until the public mind found other things to think of. The papers at first devoted pages to the event; then a few columns. In a week, one column sufficed. Finally the reports dwindled down to a single comment, and then to nothing, and the mysterious murder was practically relegated to history and forgotten.

There was one, however, who had not forgotten it, and that one was the Inspector in Chief, at Police Headquarters.

Every resource at his command had been exhausted. His best men had taken the case in hand and failed. He had personally given all the time he could spare from his other duties to the murder of Eugenie La Verde, and was yet as greatly mystified as ever. There was no palpable or reasonable solution to the problem.