The outcome of these little perceptions is therefore more efficacious than one would think. They form that je ne sais quoi, those inclinations, those images of the qualities of the senses, clear as a whole, but confused in their parts; those impressions that surrounding bodies make on us, and that embody infinity; the bond that every living being has with the rest of the universe. One may even say that as a consequence of these little perceptions the present is pregnant with the future and laden with the past, which plots all (smpnoia pnta, as Hippocrates put it), and that in the smallest of substances penetrating eyes like those of God might read all the concatenation of the things of the universe.

G. W. LEIBNIZ

CONTENTS

I

II

III

I

A PLEASURE ACCOMPANIED BY LIGHT

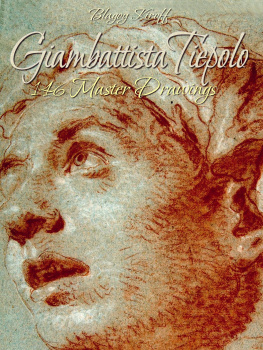

W hat happened with Tiepolo was the same thing that was to happen with certain imposing and mysterious ancient objects like the Shang bronzes: those aspects that resisted interpretation were considered decorative, while those too charged with meaning were labeled ornamental. The twenty-three Scherzi, which are a kind of Art of the Fugue in Tiepolos workvariations built on an established repertoire of characters, accessories, talismans, and gestureswere seen with some condescension as bizarre entertainments with a hint of the disquieting about them. Many took pains to repeat something that is obvious, but perhaps true: Tiepolo marks the definitive end of an epoch. But they failed to notice the unprecedented accumulation of venom and sweetness contained in that motus in fine velocior.

Tiepolo: the last breath of happiness in Europe. And, like all true happiness, it was full of dark sides destined not to fade away, but to get the upper hand. Recognizable by its effortless, unfettered air, doomed to disappear afterward. Compared with Tiepolos happiness, that of Fragonard is based on tacit exclusions. But Tiepolo excludes nothing. Not even Death, who joins the number of his characters without drawing too much attention to himself. The happiness that Tiepolo emanates did not necessarily spring from within. Perhaps there were many occasions when he told it to come back later, because right now he had a job to finish and he was behind schedule.

The ultimate peculiarity of Italian culture, the quality it could be proudest of, also because over the centuries it has proved untranslatable into other languages (whereas by contrast the meaning of the word has become obscure and remote for the majority of Italians), is what is known as sprezzatura. Baldesar Castiglione defined it as follows, in complete contrast with the thing he advised people to steer clear of as far as possible, as if from the sharpest and most dangerous rocks, in other words affectation. According to Castiglione, the remedy for the bane of affectation consisted in using in all things a certain nonchalance [sprezzatura] that may conceal art and demonstrate that what one does and says is done without effort and almost without thinking. A gloss followed: From this, I believe, does much grace derive. And a decisive consequence: It can be said that true art is that which does not seem to be art; nor should a man study anything more than the concealment of it.

For those looking for an example of sprezzatura, no one is likely to be more convincing than Tiepolo, who for a lifetime did his utmost to conceal, behind his blinding speed of execution, the subtly aberrant nature of his subjects to the point that he succeeded in having his most daring and enigmatic works, the Scherzi, passed off as facile amusements. If no one ever took Tiepolo completely seriously, we might almost say that this was what he wanted. He never had symbols and meanings assume a pose, with the result that those symbols and meanings were generally overlooked. In the Scherzi too, although no fewer than eleven of the twenty-three plates are steeped in an almost unbearable tension bound up with the act of looking at something unknown, others are imbued with a sort of torpor, as in the two portrayals of family groups at rest, one group of Satyrs and another of humans. The Scherzi have no obligatory meaning (as was the case later with Goyas The Disasters of War), but a physiological rhythm, an alternation of psychic atmospheres in which no single element prevails over the others. Even when meanings gather densely in his images with brazen insolence, Tiepolo never abandons the air of one who does things without effort and almost without thinking. He does this so well that some are led to believe he didnt think at all. And in this way he protected his thinking from intruders.

Tiepolo was a happy painter by nature, wrote his contemporary Anton Maria Zanetti, son of Alessandroand he was not forgiven for that happiness. Zanetti added: But this didnt stop him from assiduously cultivating his fertile spirit. This pleased some even less: the idea that Tiepolo possessed more erudition than he admitted to. In 1868 Charles Blanc outlined a judgment of Tiepolo that was to be picked up on and elaborated by many critics for decades: His fire is mere artifice, a firework display; his abundance has more to do with temperament than with spirit. It was therefore necessary to deny Tiepolo access to the area reserved for the spirit. But for what original sin, if not the happiness that seemed to deprive his work of a certain praiseworthy decorum? Tiepolo always had stern critics against him. This was so already during his lifetime, as Zanetti himself tells us when he mentions that Tiepolo had reawakened the dormant, happy, most graceful ideas of Paolo Caliari. The idea that Tiepolo was a sort of born-again Veronese was deeply disturbing. Hence the observation that the forms of the heads are no less graceful and beautiful; but the stern critics will let no one say that they have life and soul like those of the old Master.

After having a go in various directions (toward Piazzetta, toward Bencovich), with the frescoes in the Palazzo Patriarcale in Udine the young Tiepolo shows his hand: to bathe the world in an all-embracing light that would never be drab. And, as Giuseppe Fiocco wrote, he breaks out like a fanfare. The supremely frivolous angel that tells Sarah of the imminent birth of Isaac is also the herald of an entire tribeTiepolos tribethat for the next few decades was to spread out on the ceilings of churches and palaces, as well as on canvas and copper plates. Apparently Tiepolo was not remotely interested in subduing the totality of appearance. Right from the start he wanted to take appearance and, using invisible shears, cut out from it a segment of related and secret correspondences: between ferns and the faces of young boys, lopsided tree trunks and halberds, drapes and the busts of Nymphs and courtesans, greyhounds and ominous Orientals. Tiepolos patrons committed themselves, together with him, to welcoming his entire tribe, which moved from one neighborhood to another, from villa to villa, as far as Wrzburg and Madrid. It was the prophetic tribe with blazing eyes that Baudelaire was later to call up, an unstoppable motley caravan that dragged along with them all their assorted trappings, the flotsam and jetsam of history. They could always serve, from time to time, as scenic accessories. Without declaring or stressing this (since he never declared or stressed anything), Tiepolo allowed something to happen that would soon become an insuppressible component of all experience: the transformation of historyand of all the pastinto phantasmagoria, material suited equally to providing the scenery for a fairground sideshow or to becoming a haunting image, pure power of the mind.