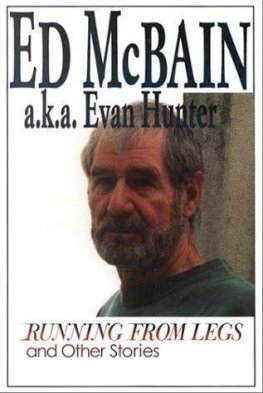

Ed McBain

a. k.a. Evan Hunter

Running From Legs and Other Stories

Only one story in this collection was published under the pseudonym Ed McBain. That one was the title story, Running From Legs, and it first saw the light of day in 1996. Most of the other stories all appeared under my own name, Evan Hunter. Three of the stories in this collection were never published anywhere before, under either name.

You may well ask why.

I will tell you why.

They were probably not good enough.

(I dont believe that for a moment.)

Because I am a master of suspense, or rather because Ed McBain is a master of suspense, I wont tell you which those three stories are until youre almost finished reading this little introduction. Instead, I will answer another question I feel certain is burning in your mind, and that is this: If only one story that follows was published under the Ed McBain pseudonym, why then does he get top billing on the cover and the title page of this book?

I will tell you why.

He is a better writer than Evan Hunter.

(I dont believe that for a moment, either.)

Otto Penzler, mystery connoisseur, maven of all crime mavens, insists that a crime story is any story that has a crime central to the plot. By his definition (and who would doubt such an expert?) Running From Legs is most definitely a crime story. He should know. He published it in an anthology called Murder for Love. But by his definition, The Last Spin, which was first published in Manhunt in 1956 (the cover of the magazine bellowing By the Author of The Blackboard Jungle!) and The Prisoner, which came out the following year, and The Interview, which was published in Playboy in 1971, are all crime stories as well and should have been published under the McBain name except that no one but my agent, my wife, and my mother (maybe) knew who Ed McBain was back then. Four out of eleven stories, however, do not a crime wave make and certainly do not constitute sufficient cause for headlining McBain over Hunter, do they? I mean, just turn the damn spotlight over to him that way? I mean, four out of eleven?

(Well, remember, three of those eleven were never published before now. Which means that half of the following stories are rightfully crime stories that fall in McBains bailiwick. Four out of eight, right?)

It wasnt until a decade after the release of the film version of The Blackboard Jungle that I hit a so-called slick magazine with a short story. This was The Fallen Angel, published in 1965 in the Ladies Home Journal, the same magazine that had serialized The Blackboard Jungle in 1954. Short story sales to Playboy followed in rapid succession both The Interview and The Sharers in 1971, the aforementioned Terminal Misunderstanding in 1972. The byline on all these stories was Evan Hunter.

Which brings us back to the essential question.

Why does McBain get top billing here, huh?

I will tell you why.

I owe a lot to him.

Hes kept me honest over the years.

If ever I begin to think Im a literary writer, he looks me square in the eye and says, Hey, come on up the precinct, pal.

If ever I begin to think my stories are too good for some simple-minded editor to appreciate, he says, Come on, theyre probably lousy.

(I dont believe that even when he says it.)

By now, I know youre wondering which of these three stories were too lousy to publish anywhere before this very instant. Well, you already have eight of the titles that were published, so a simple process of elimination should give you the three rejects. But to spare you the agony of any further excruciating suspense...

The envelopes, please.

And the losers are...

The Couple Next Door.

The Victim.

And...

Drum roll.

But You Know Us.

By my count, two Hunters and a McBain, since The Victim is probably a crime story.

That gives us a total of six Hunters and only five McBains but whos counting?

Now you know us.

Evan Hunter

Ed McBain

Weston, Connecticut

Sir, ever since the Sardinian accident, you have refused to grant any interviews...

I had no desire to join the circus.

Yet you are not normally a man who shuns publicity.

Not normally, no. The matter on Sardinia, however, was blown up out of all proportion, and I saw no reason for adding fuel to the fire. I am a creator of motion pictures, not of sensational news stories for the press.

There are some creators of motion pictures who might have welcomed the sort of publicity the Sardinian...

Not I.

Yet you will admit the accident helped the gross of the film.

I am not responsible for the morbid curiosity of the American public.

Were you responsible for what happened in Sardinia?

On Sardinia. Its an island.

On Sardinia, if you will.

I was responsible only for directing a motion picture. Whatever else happened, happened.

You were there when it happened, however...

I was there.

So certainly...

I choose not to discuss it.

The actors and technicians present at the time have had a great deal to say about the accident. Isnt there anything youd like to refute or amend? Wouldnt you like to set the record straight?

The record is the film. My films are my record. Everything else is meaningless. Actors are beasts of burden and technicians are domestic servants, and refuting or amending anything either might care to utter would be a senseless waste of time.

Would you like to elaborate on that?

On what?

On the notion that actors...

It is not a notion, it is a simple fact. I have never met an intelligent actor. Well, let me correct that. I enjoyed working with only one actor in my entire career, and I still have a great deal of respect for him or at least as much respect as I can possibly muster for anyone who pursues a profession that requires him to apply makeup to his face.

Did you use this actor in the picture you filmed on Sardinia?

No.

Why not? Given your respect for him...

I had no desire to donate fifty percent of the gross to his already swollen bank account.

Is that what he asked for?

At the time. It may have gone up to seventy-five percent by now, Im sure I dont know. I have no intention of ever giving a ploughhorse or a team of oxen fifty percent of the gross of a motion picture I created.

If we understand you correctly...

You probably dont.

Why do you say that?

Only because I have never been quoted accurately in any publication, and I have no reason to believe your magazine will prove to be an exception.

Then why did you agree to the interview?

Because I would like to discuss my new project. I have a meeting tonight with a New York playwright who will be delivering the final draft of a screenplay upon which we have laboured long and hard. I have every expectation that it will now meet my requirements. In which case, looking ahead to the future, this interview should appear in print shortly before the film is completed and ready for release. At least, I hope the timetable works out that way.

May we know who the playwright is?

I thought you were here to talk to me.

Well, yes, but...

It has been my observation that when Otto Preminger or Alfred Hitchcock or David Lean or even some of the fancy young nouvelle vague people give interviews, they rarely talk about anyone but themselves. That may be the one good notion any of them has ever contributed to the industry.