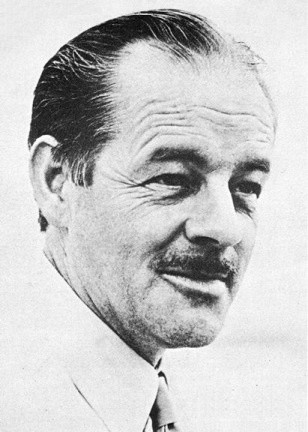

Alistair MacLean

THE DARK CRUSADER

(The Black Shrike)

1961

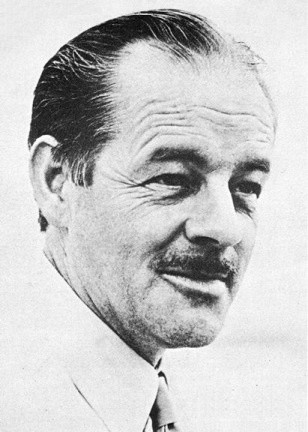

Alistair MacLean, the son of a Scots minister, was born in 1922 and brought up in the Scottish Highlands. In 1941 at the age of eighteen he joined the Royal Navy; two-and-a-half years spent aboard a cruiser was later to give him the background for HMS Ulysses, his first novel, the outstanding documentary novel on the war at sea. After the war, he gained an English Honours degree at Glasgow University, and became a school master. In 1983 he was awarded a D.Litt from the same university.

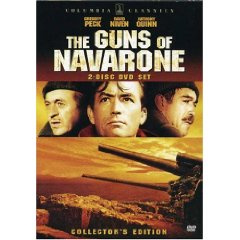

He is now recognized as one of the outstanding popular writers of the 20th century. By the early 1970s he was one of the top 10 bestselling authors in the world, and the biggest-selling Briton. He wrote twenty-nine worldwide bestsellers that have sold more than 30 million copies, and many of which have been filmed, including The Guns of Navarone, Where Eagles Dare, Fear is the Key and Ice Station Zebra. Alistair MacLean died in 1987 at his home in Switzerland.

A small dusty man in a small dusty room. Thats how I always thought of him, just a small dusty man in a small dusty room.

No cleaning woman was ever allowed to enter that office with its soot-stained heavily curtained windows overlooking Birdcage Walk: and no person, cleaner or not, was ever allowed inside unless Colonel Raine himself were there.

And no one could ever have accused the colonel of being allergic to dust.

It lay everywhere. It lay on the oak-stained polished floor surrounds that flanked the threadbare carpet. It filmed the tops of bookcases, filing cabinets, radiators, chair-arms and telephones: it lay smeared streakily across the top of the scuffed knee-hole desk, the dust-free patches marking where the papers or books had recently been pushed to one side: motes danced busily in a sunbeam that slanted through an uncurtained crack in the middle of a window: and, trick of the light or not, it needed no imagination at all to see a patina of dust on the thin brushed-back grey hair of the man behind the desk, to see it embedded in deeply trenched lines on the grey sunken cheeks, the high receding forehead.

And then you saw the eyes below the heavy wrinkled lids and you forgot all about the dust: eyes with the hard jewelled glitter of a peridot stone, eyes of the clear washed-out aquamarine of a Greenland glacier, but not so warm.

He rose to greet me as I crossed the room, offered me a cold hard bony hand like a gardening tool, waved me to a chair directly opposite the light-coloured veneered panel so incongruously let into the front of his mahogany desk, and seated himself, sitting very straight, hands clasped lightly on the dusty desk before him.

Welcome home, Bentall. The voice matched the eyes, you could almost hear the far-off crackling of dried ice. You made fast time. Pleasant trip?

No, sir. Some Midlands textile tycoon put off the plane to make room for me at Ankara wasnt happy. Im to hear from his lawyers and as a sideline hes going to drive the B.E.A. off the European airways. Other passengers sent me to Coventry, the stewardesses ignored me completely and it was as bumpy as hell. Apart from that, it was a fine trip.

Such things happen, he said precisely. An almost imperceptible tic at the left-hand corner of the thin mouth might have been interpreted as a smile, all you needed was a strong imagination, but it was hard to say, twenty-five years of minding other peoples business in the Far East seemed to have atrophied the colonels cheek muscles. Sleep?

I shook my head. Not a wink.

Pity. He hid his distress well and cleared his throat delicately. Well, Im afraid youre off on your travels again, Bentall. Tonight. Eleven p.m., London Airport.

I let a few seconds pass to let him know I wasnt saying all the things I felt like saying, then shrugged in resignation. Back to Iran?

If I were transferring you from Turkey to Iran I wouldnt have risked the wrath of the Midlands textile industry by summoning you all the way back to London to tell you so. Again the faint suggestion of a tic at the corner of the mouth. Considerably farther away, Bentall. Sydney, Australia. Fresh territory for you, I believe?

Australia? I was on my feet without realizing I had risen. Australia! Look, sir, didnt you get my cable last week? Eight months work, everything tied up except the last button, all I needed was another week, two at the most

Sit down! A tone of voice to match the eyes, it was like having a bucket of iced water poured over me. He looked at me consideringly and his voice warmed up a little to just under freezing point. Your concern is appreciated, but needless. Let us hope for your own sake that you do not underestimate our ah antagonists as much as you appear to underestimate those who employ you. You have done an excellent job, Bentall, I am quite certain that in any other government department less forthcoming than ours you would have been in line for at least an O.B.E., or some such trinket, but your part in the job is over. I do not choose that my personal investigators shall also double in the role of executioners.

Im sorry, sir, I said lamely. I dont have the overall

To continue in your own metaphor, the last button is about to be tied. It was exactly as if he hadnt heard me. This leak this near disastrous leak, I should say from our Hepworth Ordinance and Fuel Research Establishment is about to be sealed. Completely and permanently sealed. He glanced at the electric clock on the wall. In about four hours time, I should say. We may consider it as being in the past. There are those in the cabinet who will sleep well tonight.

He paused, unclasped his hands, leaned his elbows on the desk and looked at me over steepled fingers.

That is to say, they should have been sleeping well tonight. He sighed, a faint dry sound. But in these security-ridden days the sources of ministerial insomnia are almost infinite. Hence your recall. Other men, I admit, were available: but, apart from the fact that there is no one else with your precise and, in this case, very necessary qualifications, I have a faint a very faint and uneasy feeling that this may not be entirely unconnected with your last assignment. He unsteepled his fingers, reached for a pink polythene folder and slid it across the desk to me. Take a look at these, will you?

I quelled the impulse to wave away the approaching tidal wave of dust, picked up the folder and took out the half-dozen stapled slips of paper inside.

They were cuttings from the overseas vacancy columns of the Daily Telegraph. Each column had the date heavily pencilled in red at the top, the earliest not more than eight months ago: and each of the columns had an advertisement ringed in the same heavy red except for the first column which had three advertisements so marked.

The advertisers were all technical, engineering, chemical or research firms in Australia and New Zealand. The types of people for whom they were advertising were, as would have been expected, specialists in the more advanced fields of modern technology. I had seen such adverts before, from countries all over the world. Experts in aerodynamics, micro-miniaturization, hypersonics, electronics, physics, radar and advanced fuel technologies were at a premium these days. But what made those advertisements different, apart from their common source, was the fact that all those jobs were being offered in a top administrative and directorial capacity, carrying with them what I could only regard as astronomical salaries. I whistled softly and glanced at Colonel Raine, but those ice-green eyes were contemplating some spot in the ceiling about a thousand miles away, so I looked through the columns again, put them back in the folder and slid them across the desk. Compared to the colonel I made a noticeable ripple across the dustpond of the table-top.