Susanna Gregory

A GRAVE CONCERN

2016

Susanna Gregory was a police officer in Leeds before taking up an academic career. She has served as an environmental consultant during seventeen field seasons in the polar regions, and has taught comparative anatomy and biological anthropology.

She is the creator of the Matthew Bartholomew series of mysteries set in medieval Cambridge and the Thomas Chaloner adventures in Restoration London, and now lives in Wales with her husband, who is also a writer.

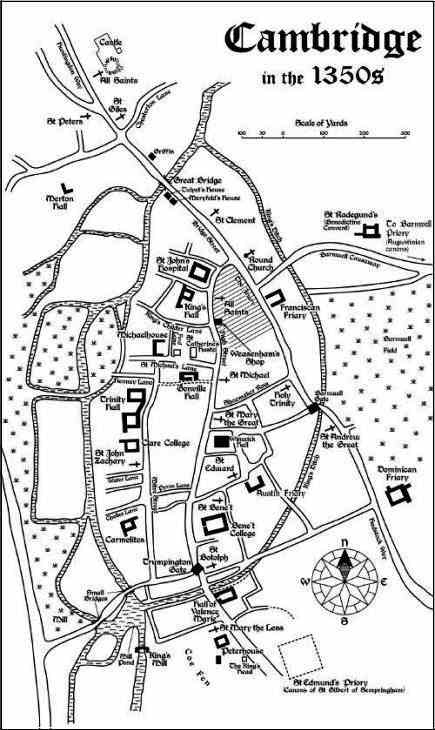

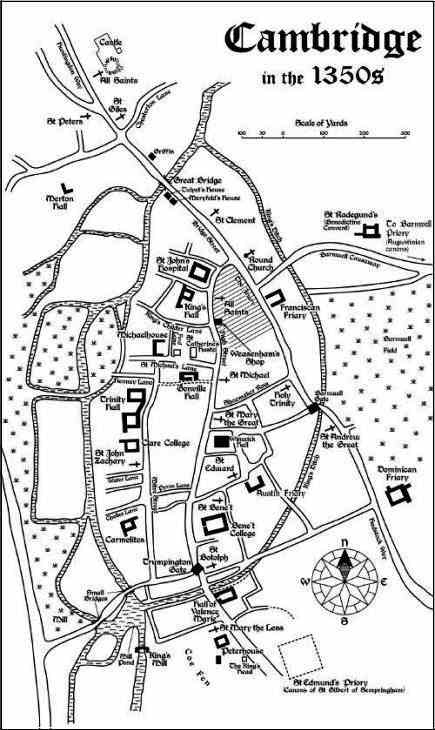

Nottingham, late summer 1359

John Dallingridge did not know who had poisoned him. He only knew he would not live to be inaugurated as a Fellow in the University at Cambridge that October, something he had wanted to do ever since childhood. He sighed at the pity of it all. He would have made an excellent teacher his students would have hung on his every word, his scholarly writings would have set the academic world afire, and his colleagues would have delighted in his mental agility.

He shifted restlessly in the bed. When he had first been afflicted by the griping pains in his innards, he had assumed that bad meat was responsible. He had been taken ill on Lammas Day after a feast at the castle, where the steward was notorious for making reckless economies. But as the days had turned into weeks and his agonies had only intensified, he began to realise that this was no innocent sickness that someone had done him deliberate and serious harm.

The toxin was slow-acting, which gave him plenty of time to ponder the culprits identity. Unfortunately, almost everyone he knew had been at the feast, and nearly all of them had set greedy eyes on the fortune he had accumulated and those who were not interested in his money were jealous of his formidable intellect or his influential connections. Yet try as he might, he had failed to determine which of them had resorted to murder.

He had woken that morning knowing his end was near. His friends and family sensed it, too, and began to gather, jostling with each other to spend a few moments at his side. They murmured impassioned promises to pray for his soul, each trying to outdo the one in front. Dallingridge grimaced. They were not there out of concern for his spiritual well-being they wanted to make sure he had not forgotten to include them in his will.

The grimace turned into a bleak smile of satisfaction, for they were all going to be disappointed. He was damned if the killer was going to benefit from the crime, and as he did not know the identity of the culprit, he had decided to disinherit everyone. Instead, every last penny of his enormous wealth would be spent on his tomb, a creation so magnificent that it would be the talk of the country. It was to be in Cambridge, because if the University he had longed to join could not have him in life, then it could house him in death.

The mason he had commissioned to build the monument was among the shuffling throng at the far end of the room, so Dallingridge beckoned him forward. His name was John Petit, a short, squat man, whose thick fingers did not look capable of producing the delicate sculptures for which he was famous.

Are you sure you understand my exact instructions? Dallingridge asked softly, anxious because so much depended on the mason doing as he was told. You will carve a good likeness of me, and set it on a canopied marble tomb-chest in Cambridges biggest and most prestigious church, just as we discussed?

Petit nodded reassuringly. It is all arranged. The scholars were more than happy to grant your request, especially once they learned the size of the donation that went with it.

Good. Dallingridge closed his eyes to indicate the conversation was over, and the mason tiptoed away. Then an unpleasant thought occurred to him.

Business had been brisk for tomb-builders immediately after the plague, as they had been inundated with requests for memorials to lost loved ones. But that was nearly ten years ago, and the backlog had been cleared. Good commissions were now few and far between, because such undertakings were expensive and only the very rich could afford them. Petit had been idly kicking his heels for the past few months, so had he acquired poison, knowing that an affluent man like Dallingridge would certainly require his services?

Dallingridge experienced a sharp stab of dismay. If so, then he had played directly into his killers hands. Not only would the monument provide work for Petit and his apprentices, but it would furnish them with an opportunity to advertise their skills in a place that had no resident tomb-makers of its own. New work would flood in, and they would be set for years.

With mounting disquiet, he looked for Petit among the well-wishers again it was not too late to dispense with his services and appoint another mason. But his eye lit instead on Richard Lakenham, an engraver of funerary brasses, who had been hired to make the six decorative shields that would be affixed to the tombs sides. Lakenham was poor, so even modest commissions were important to him. Dallingridge gulped. Was Lakenham the culprit then, desperate to earn a few shillings before he and his wife starved?

Lakenham saw Dallingridge looking at him, and started to step forward, to see if he was needed, but Petit grabbed his arm and stopped him the two men were implacable rivals and hated each other with a passion. Indignantly, Lakenham tried to break free, which resulted in an unseemly scuffle. While the other visitors watched the squabbling pair in silent disapproval, Dallingridge took the opportunity to review his shortlist of suspects for his murder, all of whom were there that day.

First, there were the folk from the castle, including its most famous prisoner Sir John Moleyns. Moleyns was a royal favourite, and the King had been outraged when a jury had convicted his old friend of theft, extortion and murder. Eager to win His Majestys favour, the Sheriff treated Moleyns like an honoured guest, providing him with sumptuous accommodation, the finest food, and the freedom to roam the city as he pleased. All Moleyns had to do in return was promise not to escape. Naturally, he had been at the Lammas Day feast, so had he indulged his penchant for unlawful killing, just for the thrill of doing it right under the Sheriffs nose? If so, Dallingridge was sorry. He rather liked Moleyns, who was entertaining, if mercurial, company.

Moleyns was standing with his wife Egidia, a cold, grasping woman, who was resentful that her husbands incarceration meant he could no longer add to the family coffers by stealing and terrorising his neighbours. Also with them was John Inge, Moleyns lawyer, whom Dallingridge disliked intensely. Inge was sly, secretive and duplicitous, and it was common knowledge that he would do anything for money.

Dallingridge eyed the three of them thoughtfully. Since he had announced that he was dying, they had made it their business to call on him every day, purely in the hope of getting money. Moleyns had been rich, but most of his property was confiscated by the courts, so a legacy would suit him very nicely. Meanwhile, Inge and Egidia hated relying on Moleyns for the occasional hand-out, and longed to be financially independent. Could one of them have killed him, in the hope of acquiring enough cash to tide them over until the King arranged for Moleyns to be released?