ORHAN PAMUK expresses his gratitude to Sila Okur for ensuring fidelity to the Turkish text; to his editor and friend George Andreou, for his meticulous editing of the translation; and to Kiran Desai for generously giving her time to read the final text, and for her invaluable suggestions and ideas.

7 The Merhamet Apartments

MY MOTHER had bought the flat in the Merhamet Apartments twenty years earlier, partly as an investment, and partly as a place where she could retire occasionally for some peace and quiet; but before long she began to use it as a depot for old furniture she deemed to have gone out of fashion and new acquisitions that she immediately found tiresome. As a boy I had liked the back garden, where neighborhood children used to play football in the shade of the giant trees, and I had always loved the story my mother enjoyed telling about the name.

After Atatrk instructed the Turkish people to take surnames for themselves in 1934, it became fashionable to attach ones new name to ones newly constructed apartment building. Since in those days there was no consistent system for street names and numbers, and large, wealthy families tended to live collectively under one roof, just as they had done in the days of the Ottoman Empire, it made sense for the sake of navigating the city that these new apartment buildings be known by the name of the owners. (Many of the rich families I shall mention own eponymous apartment buildings.) Another aspirational fashion was for people to name buildings after high-minded principles; but my mother would say that those who gave their buildings names like Hrriyet (freedom), nayet (benevolence), or Fazilet (charity) were generally the ones who had spent their entire lives making a mockery of those same virtues. The Merhamet (mercy) Apartments had been built by a rich old man who had controlled the black market in sugar during the First World War and later felt compelled to philanthropy. His two sons (the daughter of one of them was my classmate in primary school), upon discovering that their father planned to turn the apartment house over to a charity, distributing any income it generated to the poor, had their father declared incompetent and put him into a home for the indigent, whereupon they took possession of the building, but without bothering to change the name that I had found so peculiar as a child.

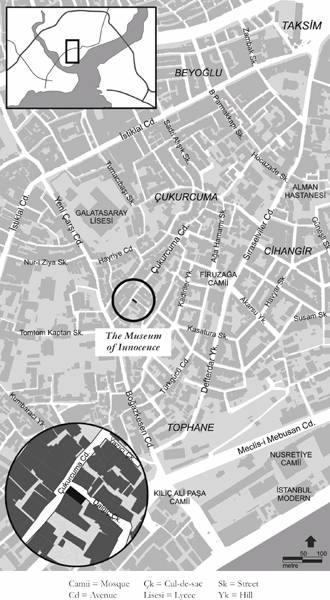

On the following day, Wednesday, April 30, 1975, I sat in the Merhamet Apartments between 2 and 4 p.m., waiting for Fsun, who never came. I was a little heartbroken and confused; returning to the office, I felt troubled. The next day I went back to the apartment, as if to temper my disquiet, but again Fsun didnt come. Sitting in those airless rooms, surrounded by my mothers old vases and dresses and dusty discarded furniture, going one by one through my fathers amateurish snapshots, I recalled moments from my childhood and youth that I hadnt even realized Id forgotten, and it seemed as if these artifacts had the power to calm my nerves. The next day, while eating lunch at Hac Arifs Restaurant in Beyolu with Abdlkerim, the Kayseri dealer of Satsat (and a friend from my army days), I recalled with shame that I had spent two consecutive afternoons waiting for Fsun in an empty apartment. I was so embarrassed I decided to forget about her, the fake handbag, and everything else. But twenty minutes later, as I glanced at my watch, it occurred to me that Fsun might be walking toward the Merhamet Apartments at that very moment with the refund for the handbag; making up a lie for Abdlkerim, I wolfed down my food and rushed off.

Twenty minutes after I got there, Fsun rang the bell. Or rather, the person who could only be Fsun rang the bell. As I ran to the door I remembered that the previous night I had opened the door to her in a dream.

In her hand was an umbrella. Her hair was dripping wet. She was wearing a yellow pointille dress.

Well, well, well, I thought youd forgotten all about me. Come on in.

I dont want to disturb you. Let me just give you the money and go. In her hand was a worn envelope on which were imprinted the words Outstanding Achievement Course, but I didnt take it. Taking hold of her shoulder, I pulled her inside and shut the door.

Its raining hard, I said, although Id not noticed the rain myself. Sit for a while. Theres no reason why you should rush out into the rain and get wet again so soon. Im making some tea. At least warm yourself up. I headed for the kitchen.

When I returned, Fsun was looking over my mothers old furniture, her antiques, dusty clocks, hatboxes, and accessories. To make her feel more at home, and to encourage conversation, I told her how my mother had bought all these things on impulse from the most fashionable shops of Beyolu and Nianta, pashas mansions whose furnishings were being sold off, Bosphorus yalis half destroyed by fire, antique dealers, and even vacated dervish lodges, not to mention all the shops she visited on her European travels, but that after using them for a short while she brought them here and forgot all about them. At the same time I was opening trunks packed with clothes reeking of mothballs, and the tricycle that wed both ridden as children (my mother was in the habit of giving our old ones to poor relations), a chamber pot, and finally the Ktahya vase that my mother had asked me to find for her; then I showed her the hats, box by box.

A crystal sweet bowl reminded us of holiday feasts she had attended. When shed arrive with her parents for their holiday visit, theyd be offered an assortment of sugar and almond candies, marzipan, sugar-covered coconut lion bars, and lokum, or Turkish delight.

Once when we came here for the Feast of the Sacrifice, I remember we went out for a ride in the car, said Fsun, her eyes shining.

I remembered that outing. You were a child then, I said. Now you have become a very beautiful and enchanting young woman.

Thank you. I should leave now.

You havent even drunk your tea. And the rain hasnt stopped. I pulled her over to the balcony door, gently parting the tulle curtain. She looked out the window; in her eyes was the light that you see only in children arriving at a new place, or in young people still open to new influences, still curious about the world because they have not yet been scarred by life. For a moment I gazed longingly at her neck, the nape of her neck, and her fine complexion, which made her cheeks so beautiful, and the countless freckles on her skin, which were invisible from a distance (hadnt my grandmother had such freckles?). My hand, as if it was someone elses, reached out and took hold of the barrette in her hair. Painted on it were four sprigs of verbena.

Your hair is very wet.

Did you tell anyone that I cried in the shop?

No. But Im very curious to know what made you cry.

Why?

Ive been spending a lot of time thinking about you, I said. Youre very beautiful, very different from anyone else. I remember so well what a lovely little dark-haired girl you were. But I never imagined you would turn into such a beauty.

She smiled the measured smile of well-mannered beauties accustomed to compliments, but at the same time she raised her eyebrows in suspicion. There was a silence. She took one step back.

So what did enay Hanm say? I asked, changing the subject. Did she happen to acknowledge that the handbag was a fake anyway?

She was very annoyed when she realized you had demanded your money back, but she didnt want to make a drama about it. She told me just to forget the whole thing. She knew the bag was a fake, I guess. She doesnt know Im here. I told her that youd stopped by at lunchtime to collect the money. I really have to go now.