ALSO BY

E LENA F ERRANTE

The Days of Abandonment

Troubling Love

The Lost Daughter

The Beach at Night

Frantumaglia: A Writers Journey

Incidental Inventions

The Lying Life of Adults

M Y B RILLIANT F RIEND

(The Neapolitan Quartet)

My Brilliant Friend

The Story of a New Name

Those Who Leave and Those Who Stay

The Story of the Lost Child

IN THE MARGINS

E DITORS N OTE

T his book originated in an email from Professor Costantino Marmo, director of the Centro Internazionale di Studi Umanistici Umberto Eco. It read, in part:

I like to think that the autumn of 2020 would be the ideal time for Elena Ferrante to give three lectures at the University of Bologna, on three successive days, open to the entire city. These lectures would discuss her work as a writer, her poetics, her narrative technique, or anything else she wants, and would ideally be of interest to a broad, non-specialist audience.

The Eco Lectures belong to a tradition of lectures given by figures from the national and international world of culture which Umberto Eco, then director of the Scuola Superiore di Studi Umanistici, decided to offer the university and the city of Bologna in the early years of this century. The first series was given by Elie Wiesel (in January of 2000), the most recent by Orhan Pamuk (in the spring of 2014).

Then came the pandemic and the lockdowns, and public events were impossible. In the meantime, however, Ferrante, having accepted the invitation, had written the three lectures. And so in November of 2021 the actress Manuela Mandracchia, in the guise of Elena Ferrante, presented the lectures at the Teatro Arena del Sole in Bologna, together with ERT, Emilia Romagna Teatro.

The authors exploration of reading and writing continues here with Dantes Rib, an essay composed at the invitation of the ADI, the Association of Italianists, under the auspices of Professor Alberto Casadei and the president of the ADI, Gino Ruozzi. The essay concluded the conference Dante and Other Classics (April 29, 2021), where it was read by the scholar and critic Tiziana de Rogatis.

Sandra Ozzola

P AIN AND P EN

L adies and gentlemen,

this evening Im going to talk to you about the desire to write and about the two kinds of writing it seems to me I know best, the first compliant, the second impetuous. But I will begin, if I may, by devoting a few lines to a child Im very fond of and her first attempts at the alphabet.

Recently Ceciliaas I will call her herewanted to show me how well she was able to write her name. I gave her a pen and a sheet of paper from the printer, and she commanded: Watch. Then, with intense concentration, she wrote Cecilialetter by letter, in capitalsher eyes narrowed as if she were facing some danger. I was pleased, but also a little anxious. Once or twice I thought: Now Ill help her, guide her handI didnt want her to make a mistake. But she did it all by herself. She didnt worry in the least about starting off at the top of the page. She aimed sometimes up, sometimes down, assigning the letterseach consonant, each vowelrandom dimensions, one big, one small, one medium-sized, leaving a lot of space between the individual marks. Finally she turned to me and, almost shouting, said, See?, with an imperative need to be praised.

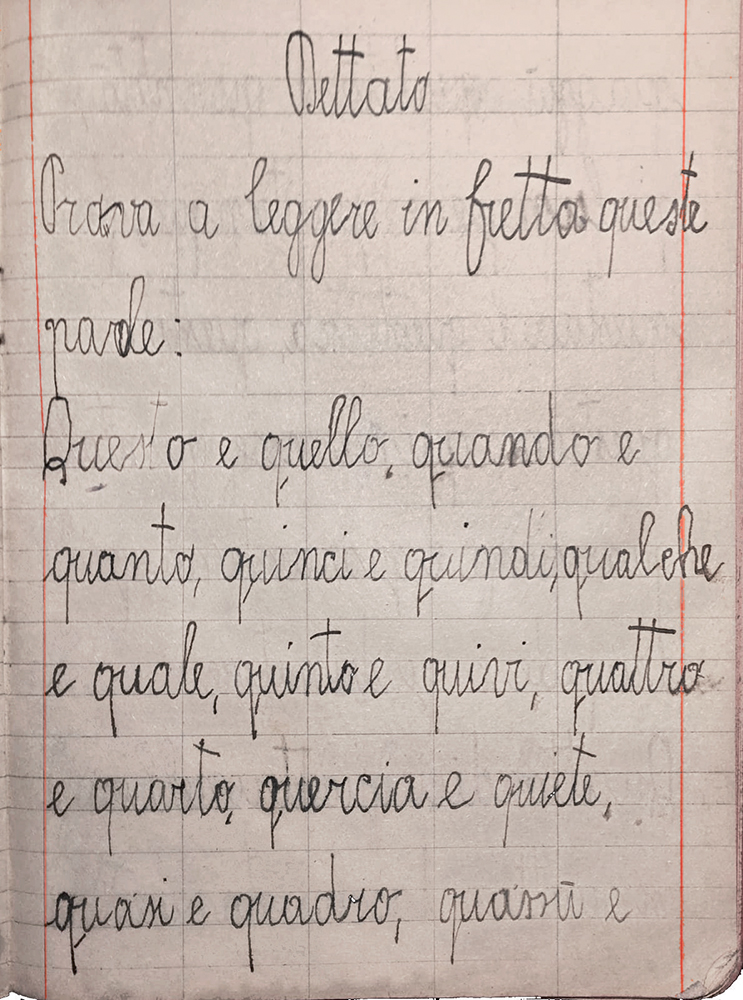

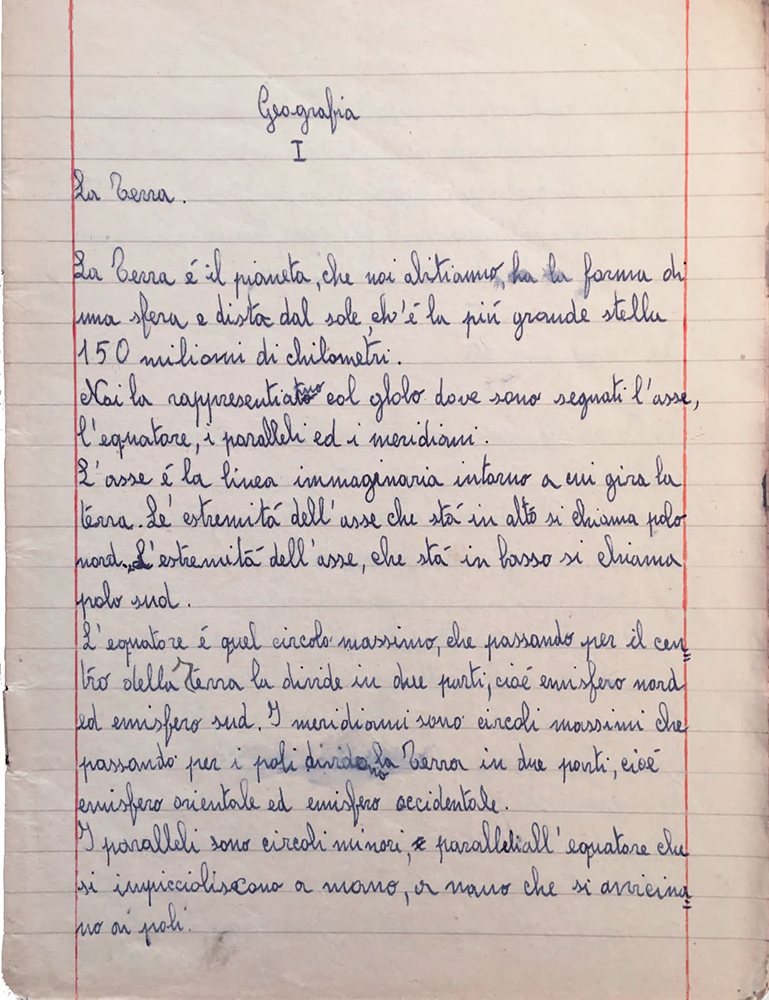

Naturally I feted hereffusivelybut I felt a little uneasy. Why that fear that she would make a mistake? Why that impulse of mine to guide her hand? Ive thought about it lately. Surely, many decades earlier, I, too, had written in the same irregular manner, on some random piece of paper, with the same concentration, the same apprehension, the same need for praise. But, in all honesty, I have to say I have no memory of doing so. My first memories of writing have to do with elementary-school notebooks. They hadI dont know if they still dohorizontal black lines, unevenly spaced, so that they defined areas of different sizes. Like this:

The size of these areas changed from first grade to fifth. If you disciplined your hand and learned to line up small, round letters and letters that ascended or descended, you passed, and the horizontal segments that divided the page got smaller from year to year until they became, in fifth grade, a single line. Like this:

You were big by nowyou had begun your school journey at six and now you were tenand you were big because your writing flowed in an orderly way across the page.

Flowed where? Well, defining the white page were not only the horizontal black lines but two vertical red lines, one on the left, one on the right. The writing was supposed to move between those lines, and those linesof this I have a very clear memorytormented me. They were intended to indicate, by their color as well, that if your writing didnt stay between those taut lines you would be punished. But I was easily distracted when I wrote, and while I almost always respected the margin on the left, I often ended up outside the one on the right, whether to finish the word or because I had reached a point where it was difficult to divide the word into syllables and start a new line without going outside the margin. I was punished so often that the sense of the boundary became part of me, and when I write by hand I feel the threat of the vertical red line even though I havent used paper like that for years.

What to say? Today I suspect that my writinglets saylike Cecilias, ended up in or under the writing in those notebooks. I dont remember it, and yet it must be there, educated at last to stay on the lines and between the margins. Probably that first effort is the matrix from which I still get a self-congratulatory sense of victory whenever something obscure suddenly emerges from invisibility to become visible, thanks to a sequence of marks on the page or the computer screen. Its a provisional alphabetical combination, surely imprecise, but I have it before my eyes, very close to the brains first impulses and yet here, outside, already detached. There is such a childish magic to this that if I had to symbolize its energy in graphic form I would use the disorderly way Cecilia wrote her name, insisting that I watch her and in those letters see her and enthusiastically recognize her.

In my longing to write, starting in early adolescence, both the threat of those red linesmy handwriting now is very neat, and when Im using the computer I go, after a paragraph or so, to the alignment icon and click on the option that evens the marginsand the desire and fear of violating them are probably at work. More generally, I believe that the sense I have of writingand all the struggles it involveshas to do with the satisfaction of staying beautifully within the margins and, at the same time, with the impression of loss, of waste, because of that success.

I started with a child trying to write her name, but now, to continue, Id like to invite you to look for a moment between the lines of Zeno Cosini, the protagonist of Italo Svevos greatest book, Zenos Conscience. Were catching Zeno right in the effort of writing, and his effort, in my eyes, isnt that far from Cecilias.

Now, having dined, comfortably lying in my overstuffed lounge chair, I am holding a pencil and a piece of paper. My brow is unfurrowed because I have dismissed all concern from my mind. My thinking seems something separate from me. I can see it. It rises and falls... but that is its only activity. To remind it that it is my thinking and that its duty is to make itself evident, I grasp the pencil. Now my brow does wrinkle, because each word is made up of so many letters and the imperious present looms up and blots out the past.