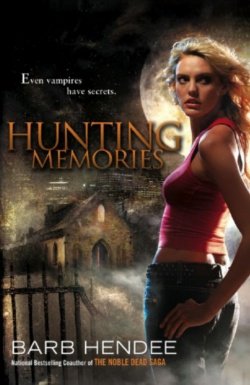

Barb Hendee

Blood Memories

For J. C. and Elaine, who never quite got the hang of people, but always save lost kittens from the rain.

I was with Edward the day he killed himself.

It happens to us sometimes, especially the old, the ones who've lost the joy of then and can't quite grasp the now. I don't know why. But I'd never seen it until that morning Edward jumped off his own front porch and exploded in the sun like a gas fire.

We'd been friends for a long time. I know everyone else thought we were mad for living in the same city. But he stayed out of my hunting territory, and I stayed out of his. Besides, sometimes it was nice to talk to someone without lying.

I was on my way out at about two o'clock that morning when the phone rang.

"Hello."

"Eleisha, it's me. I wanted to tell you good-bye."

He'd never called me before, but Edward's accent combined traces of a British accent with a New York pace. I'd have known it anywhere.

"What do you mean, good-bye?"

"This house is bright and loud," he whispered. "I don't think I can live here anymore."

That didn't make sense. He'd been in the same house since 1937.

"Did you buy a new place? Do you need me to help you move?"

"No. That wouldn't help. One place is the same as another. I don't belong now, Eleisha. A new house would be worse."

Something in his calm whisper frightened me, like tiny invisible fingers digging under my skin.

"Edward, stay there. I'm coming over."

"Do you think that will help? I don't think so."

"Just stay there."

Money isn't really a problem for me, so neither are traffic tickets although attracting police under any condition is a bad idea. But not caring who pulled me over, I hit ninety on the freeway that night driving to Edward's. I just couldn't see him freaking out. He wasn't the type. We'd both been warned about time adjustments, but he did all the right things: read contemporary magazines, updated his wardrobe, and saved a collection of personal items from the past to keep his history intact.

Everything.

I tended to interact a lot more with the general populace than he did. He might have been a bit of a recluse, but not to the point of being unusual. He even took occasional trips back to Manhattan or London just to unwind.

When I pulled up to the house, the music of his Tchaikovsky album was pouring out the windows at max volume, loud enough to wake the neighbors. Thinking about his albums made me remember I'd been buying him CDs for the past five years and he never played them.

"Turn it down," I said, slipping through his front door, "before some pissed-off housewife calls the cops."

"Eleisha," he said, smiling. "What are you doing here?"

I almost backed up when he stepped onto the soft carpet of the front hallway. Dressed in an old pair of sweatpants-and nothing else-he looked half starved, with blue-black circles under both eyes.

"Edward, what are? What's wrong with you?"

"Wrong? Nothing. I've been cooking. Do you remember cooking? I went shopping last night and found a leg of mutton in the meat department at Safeway. Can you believe it? In this cultural wasteland? A leg of mutton?"

I felt cold. "Jesus, have you been trying to eat?"

"Cooking. Cooking is a lost art."

He looked about thirty-three, with mink-brown hair and dark green, bloodshot eyes. I'd never seen the whites of his eyes completely clear. He loved simple pleasures and elitist luxuries like imported tobacco and suits from Savile Row. People were attracted to him because he played the perfect, sweet, vogue, vague snob. He was the sanest vampire I'd ever known.

"What did you eat?" No wonder he was sick.

"Come and see."

"Turn the stereo down first."

The smell from the kitchen nauseated me. Looking through the bar-styled doors, I saw what he'd been doing, and I'd never felt so lost.

A dead Doberman lay on the table, dried blood crusted on its black and brown muzzle. Three decomposing cats had been thrown into a heap of rotting vegetables on the counter. He'd also been shopping. There were brown Safeway bags strewn all over the floor. I couldn't take it all in at once: cartons of spoiled milk, broken lightbulbs, whole fryer chickens, mashed potatoes, and dirty dishes. Streaks of dried blood smeared the walls.

He pushed past me and picked up a grocery bag.

"Paper or plastic?" He smiled.

I grabbed it out of his hand. "We've got to clean this up. What if somebody comes in here when you're asleep? Are you listening to me? What do you think will happen if someone sees this? They'll think you've lost it."

"I have lost it, baby." He fell into his uptown cool routine. "So have you. Just two little productive members of society, aren't we? Keeping the population down. You know, I've been thinking we might move to China. They could certainly use us there."

"Stop it. You're scaring me."

"Really? We can't have that, now can we?"

My kind has no doctors or lawyers or psychologists to help us. We don't have group therapy for undeads who slip out of reality. I remember feeling angry at myself because I didn't know what to do. How bad off was he? Would he get better?

I handed back his grocery bag and pushed the hair out of his eyes. "Don't take this out on me. Let's just clean up this mess and go hunting. We haven't been hunting together since that New Year's Eve party at the Red Lion in 'seventy-eight."

That was a great party. Edward always looked hot in a black tux.

"Can't," he whispered.

"What do you mean, you can't? You have to feed."

"I can't. I don't want to."

"Okay, then come and stay with me and William for a few months. Maybe you're spending too much time alone."

William is an old man who lives with me. I'll talk more about him later.

"And then what?" He dropped the bag and looked straight at me through his cold, green, bloodshot eyes. "A few months? Hardly worth noticing to someone like you, is it? Nothing would change in the world around us besides the skirt length in Paris and Tom Cruise finding his next wife. What happens in ten years? Twenty? I see the same face every day when I look in the mirror. It never changes."

"I know. You just have to deal with it."

"Don't you get tired of seeing the same face every day?"

"Sometimes."

He smiled again and picked up a butcher knife lying by the dead cats. "I could change it for you. But that wouldn't matter either, would it? You'd look the same in a week, so it wouldn't do you any good, unless I cut your head off."

I backed up. "Do you want me to leave?"

"I don't care what you do."

"Fine. You stay here in this pig pit and talk to yourself. But you'd better get it together and clean this mess up by morning, or it's going to stink and get some nosy neighbor poking around in your stuff."

"By morning it won't matter," he whispered.

I turned back to him in frustration. "Edward, what's wrong? Let's just get out of here. Let's go to my place."

"No, it's too late I'm sick of it all, Lady Leisha."

He hadn't called me that in over a hundred years. It was a nickname he'd picked for me when I first stepped off the boat from Wales in 1839, looking like a frightened, half-drowned mouse. He'd been so nice to me back then.

Softly grasping his wrist, I pulled him down to a crouched position on the floor. "Talk to me."

"Do you remember church? I don't mean the religion itself, but how we used to wonder about death?"

"I remember, but I don't think about it very often. Should we?" He pushed me back against the bloody kitchen wall, and then he lay down on the floor with his head in my lap. I wrapped my arms around him, and his butcher knife clattered harmlessly onto the checkerboard linoleum.