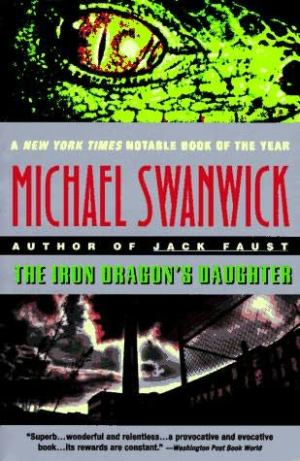

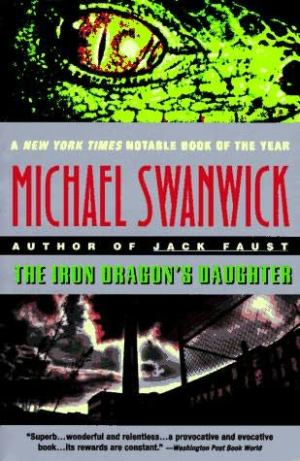

The Iron Dragon's Daughter

MICHAEL SWANWICK

FOR TESS KISSINGER AND BOB WALTERS

who didn't suspect I was stealing part of their story

The author is grateful to Greg Frost for his encouragement and suggestions and for spotting the significance of the shadow-boy, Bob and Tess for dirt on insurgencies and rich relations, Susan Duggan for help navigating Penn, Dr. David Van Dyke for the p-chem here misapplied and for electric pickles as well, Gardner and Susan for football yobboes, Janet Kagan for help with French neologisms, Dafydd ab Hugh for Celtic words left on the cutting room floor, Gail Roberts for Dickens references, Elizabeth Willey for funding the University's carillon and one of its bathrooms, Lucia St. Clair Robson for the Gordon Riots and the Half-Crown Chuck Office, and Sean for his many insights. Health insurance and emotional support were provided by the M.C. Porter Endowment for the Arts.

THE CHANGELING'S DECISION TO STEAL A DRAGON AND ESCAPE was born, though she did not know it then, the night the children met to plot the death of their supervisor.

She had lived in the steam dragon plant for as long as she could remember. Each dawn she was marched with the other indentured minors from their dormitory in Building 5 to the cafeteria for a breakfast she barely had time to choke down before work. Usually she was then sent to the cylinder machine shop for polishing labor, but other times she was assigned to Building 12, where the black iron bodies were inspected and oiled before being sent to the erection shop for final assembly. The abdominal tunnels were too small for an adult. It was her duty to crawl within them to swab out and then grease those dark passages. She worked until sunset and sometimes later if there was a particularly important dragon under contract.

Her name was Jane.

The worst assignments were in the foundries, which were hellish in summer even before the molds were poured and waves of heat slammed from the cupolas like a fist, and miserable in winter, when snow blew through the broken windows and a gray slush covered the work floor. The knockers and hogmen who labored there were swart, hairy creatures who never spoke, blackened and muscular things with evil red eyes and intelligences charred down to their irreducible cinders by decades-long exposure to magickal fires and cold iron. Jane feared them even more than she feared the molten metals they poured and the brute machines they operated.

She'd returned from the orange foundry one twilit evening too sick to eat, wrapped her thin blanket tight about her, and fallen immediately asleep. Her dreams were all in a jumble. In them she was polishing, polishing, while walls slammed down and floors shot up like the pistons of a gigantic engine. She fled from them under her dormitory bed, crawling into the secret place behind the wallboards where she had, when younger, hidden from Rooster's petty cruelties. But at the thought of him, Rooster was there, laughing meanly and waving a three-legged toad in her face. He chased her through underground caverns, among the stars, through boiler rooms and machine shops.

The images stabilized. She was running and skipping through a world of green lawns and enormous spaces, a strangely familiar place she knew must be Home. This was a dream she had often. In it, there were people who cared for her and gave her all the food she wanted. Her clothes were clean and new, and nobody expected her to put in twelve hours daily at the workbench. She owned toys.

But then as it always did, the dream darkened. She was skipping rope at the center of a vast expanse of grass when some inner sense alerted her to an intrusive presence. Bland white houses surrounded her, and yet the conviction that some malevolent intelligence was studying her increased. There were evil forces hiding beneath the sod, clustered behind every tree, crouching under the rocks. She let the rope fall to her feet, looked about wonderingly, and cried a name she could not remember.

The sky ripped apart.

"Wake up, you slattern!" Rooster hissed urgently. "We coven tonight. We've got to decide what to do about Stilt."

Jane jolted awake, heart racing. In the confusion of first waking, she felt glad to have escaped her dream, and sorry to have lost it. Rooster's eyes were two cold gleams of moonlight afloat in the night. He knelt on her bed, bony knees pressing against her. His breath smelled of elm bark and leaf mold intermingled. "Would you mind moving? You're poking into my ribs."

Rooster grinned and pinched her arm.

She shoved him away. Still, she was glad to see him. They'd established a prickly sort of friendship, and Jane had come to understand that beneath the swagger and thoughtlessness, Rooster was actually quite nice. "What do we have to decide about Stilt?"

"That's what we're going to talk about, stupid!"

"I'm tired," Jane grumbled. "I put in a long day, and I'm in no mood for your hijinks. If you won't tell me, I'm going back to sleep."

His face whitened and he balled his fist. "What is thismutiny? I'm the leader here. You'll do what I say, when I say, because I say it. Got that?"

Jane and Rooster matched stares for an instant. He was a mongrel fey, the sort of creature who a century ago would have lived wild in the woods, emerging occasionally to tip over a milkmaid's stool or loosen the stitching on bags of milled flour so they'd burst open when flung over a shoulder. His kind were shallow, perhaps, but quick to malice and tough as rats. He worked as a scrap iron boy, and nobody doubted he would survive his indenture.

At last Jane ducked her head. It wasn't worth it to defy him.

When she looked up, he was gone to rouse the others. Clutching the blanket about her like a cloak, Jane followed. There was a quiet scuffling of feet and paws, and quick exhalations of breath as the children gathered in the center of the room.

Dimity produced a stolen candle stub and wedged it in the widest part of a crack between two warped floorboards. They all knelt about it in a circle. Rooster muttered a word beneath his breath and a spark leaped from his fingertip to the wick.

A flame danced atop the candle. It drew all eyes inward and cast leaping phantasms on the walls, like some two-dimensioned Walpurgisnacht. Twenty-three lesser flames danced in their irises. That was all dozen of them, assuming that the shadow-boy lurked somewhere nearby, sliding away from most of the light and absorbing the rest so thoroughly that not a single photon escaped to betray his location.

In a solemn, self-important voice, Rooster said: "Blugg must die." He drew a gooly-doll from his jerkin. It was a misshapen little thing, clumsily sewn, with two large buttons for eyes and a straight gash of charcoal for a mouth. But there was the stench of power to it, and at its sight several of the younger children closed their eyes in sympathetic hatred. "Skizzlecraw has the crone's-blood. She made this." Beside him, Skizzlecraw nodded unhappily. The gooly-doll had been her closely guarded treasure, and the Lady only knew how Rooster had talked her out of it. He brandished it over the candle. "We've said the prayers and spilt the blood. All we need do now is sew some touch of Blugg inside the stomach and throw it into a furnace."

"That's murder!" Jane said, shocked.

Thistle snickered.

"I mean it! And not only is it wrong, but it's a stupid idea as well." Thistle was a shifter, as was Stilt himself, and like all shifters she was something of a lack-wit. Jane had learned long ago that the only way to silence Thistle was to challenge her directly. "What good would it do? Even if it workedwhich I doubtthere'd be an investigation afterwards. And if by some miracle we weren't discovered, they'd still only replace Blugg with somebody every bit as bad. So what's the point of killing him?"

Next page