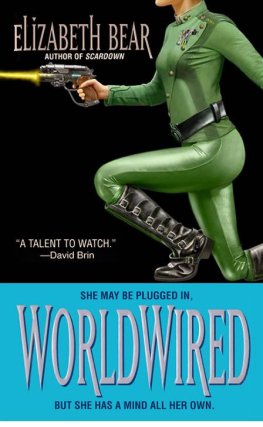

Elizabeth Bear

Worldwired

Jenny Casey -3

To Kit

It takes a lot of people to write a novel. This one would not have existed without the assistance of my very good friends and first readers (on and off the Online Writing Workshop for Science Fiction, Fantasy, and Horror) especially but not exclusively Kathryn Allen, Chris Coen, Jaime Voss, James Stevens-Arce, Michael Curry, Ruth Nestvold, Chris Manucy, Bonnie Freeman, Holly McDowell, Ejner Fulsang, Larisa Walk, John Tremlett, Amanda Downum, and Leah Bobet. I am also indebted to Stella Evans, M.D., to whom I owe whatever bits of the medical science and neurology are accurate; Peter Watts, Ph.D., for assistance with questions of biology; M.Cpl. S. K. S. Perry (Canadian Forces), Lt. Penelope K. Hardy (U.S. Navy), and Capt. Beth Coughlin (U.S. Army), without whom my portrayal of military life would have been even more wildly fantastical; Leonid Korogodski and Claris Cates-Smith Ryan for linguistic assistance; engineer Catherine Morrison and recovering biologist Jeremy Tolbert for fielding questions about rising sea levels, alien microbiology, and decontamination procedures; safety engineer Wendy S. Delmater; Meredith L. Patterson, linguist and computer geek, for assistance with interspecies semiotics; Melinda Goodin for Australian Rules English assistance; Stephen Shipman, for AI geekery; Chelsea Polk and Kellie Matthews for bolstering my knowledge of the native music of Soviet Canuckistan; Celia Marsh for emergency, just-in-time delivery of vintage Kate and Anna McGarrigle; Steven Brust and Caliann Graves, for advice and tolerance; Dena Landon, Sarah Monette, and Kelly Morisseau, francophones extraordinaire, upon whom may be blamed any correctness in the Qubecois especially the naughty bits; my agent, Jennifer Jackson, my copyeditor, Faren Bachelis, and my editor, Anne Groell, for too many reasons to enumerate; and to Kit Kindred, who is patient with the foibles of novelism.

For the sake of accuracy, I should note that in the interests of drama, my United Nations bears about the same resemblance to the real one that an episode of Perry Mason bears to an actual criminal proceeding.

The failures, of course, are my own.

In the interests of presenting a detailed personal perspective on a crucial moment in history, we have taken the liberty of rendering Master Warrant Officer Casey's interviews as preserved in the Yale University New Haven archives in narrative format. Changes have been made in the interests of clarity, but the words, however edited, are her own.

The motives of the other individuals involved are not as well documented, although we have had the benefit of our unique access to extensive personal records left by Col. Frederick Valens. The events as presented herein are accurate: the drives behind them must always remain a matter of speculation, except in the case of Dr. Dunsany who left us comprehensive journals and Dr. Feynman, who kept frequent and impeccable backups.

Thus, what follows is a historical novel, of sorts. It is our hope that this more intimate annal than is usually seen will serve to provide future students with a singular perspective on the roots of the civilization we are about to become.

Patricia Valens, Ph.D.

Jeremy Kirkpatrick, Ph.D.

One cannot walk the Path until one becomrs the Path

Gautama Buddha

10:30 AM

27 September 2063

HMCSSMontreal

Earth orbit

I've got a starship dreaming. And there it is. Leslie Tjakamarra leaned both hands on the thick crystal of the Montreal's observation portal, the cold of space seeping into his palms, and hummed a snatch of song under his breath. He couldn't tell how far away the alien spaceship was at least, the fragment he could see when he twisted his head and pressed his face against the port. Earthlight stained the cage-shaped frame blue-silver, and the fat doughnut of Forward Orbital Platform was visible through the gaps, the gleaming thread of the beanstalk describing a taut line downward until it disappeared in brown-tinged atmosphere over Malaysia. Bloody far, he said, realizing he'd spoken out loud only when he heard his own voice. He scuffed across the blue-carpeted floor, pressed back by the vista on the other side of the glass.

Someone cleared her throat behind him. He turned, although he was unwilling to put his back to the endless fall outside. The narrow-shouldered crew member who stood just inside the hatchway met him eye to eye, the black shape of a sidearm strapped to her thigh commanding his attention. She raked one hand through wiry salt-and-pepper hair and shook her head. Or too close for comfort, she answered with an odd little smile. That's one of the ones Elspeth calls the birdcages

Elspeth?

Dr. Dunsany, she said. You're Dr. Tjakamarra, the xenosemiotician. She mispronounced his name.

Leslie, he said. She stuck out her right hand, and Leslie realized that she wore a black leather glove on the left. You're Casey, he blurted, too startled to reach out. She held her hand out until he recovered enough to shake. I didn't recognize

It's cool. She shrugged in a manner entirely unlike a living legend, and gave him a crooked, sideways grin, smoothing her dark blue jumpsuit over her breasts with the gloved hand. We're all different out of uniform. Besides, it's nice to be looked at like real people, for a change. Come on. The pilots' lounge has a better view.

She gestured him away from the window; he caught himself shooting her sidelong glances, desperate not to stare. He fell into step beside her as she led him along the curved ring of the Montreal's habitation wheel, the arc rising behind and before them even though it felt perfectly flat under his feet.

You'll get used to it, Master Warrant Officer Casey said, returning his looks with one of her own. It said she had accurately judged the reason he trailed his right hand along the chilly wall. Here we are She braced one rubber-soled foot against the seam between corridor floor and corridor wall, and expertly spun the handle of a thick steel hatchway with her black-gloved hand. Come on in. Step lively; we don't stand around in hatchways shipboard.

Leslie followed her through, turning to dog the door as he remembered his safety lectures, and when he turned back Casey had moved into the middle of a chamber no bigger than an urban apartment's living room. The awe in his throat made it hard to breathe. He hoped he was keeping it off his face.

There, Casey said, stepping aside, waving him impatiently forward again. That's both of them. The one on the left' is the shiptree. The one on the right' is the birdcage.

Everyone on the planet probably knew that by now. She was babbling, Leslie realized, and the small evidence of her fallibility and her own nervousness did more to ease the pressure in his chest than her casual friendliness could have. You're acting like a starstruck teenager, he reprimanded himself, and managed to grin at his own foolishness as he shuffled forward, his slipperlike ship-shoes whispering over the carpet.

Then he caught sight of the broad sweep of windows beyond and his personal awe for the woman in blue was replaced by something visceral. He swallowed, throat dry.

The Montreal's habitation wheel spun grandly, creating an imitation of gravity that held them, feet-down, to the floor. Leslie found himself before the big round port in the middle of the wall, hands pressed to either rim as if to keep himself from tumbling through the crystal like Alice through the looking glass. The panorama rotated like a merry-go-round seen from above. Beyond it, the soft blue glow of the wounded Earth reflected the sun. The planet's atmosphere was fuzzed brown like smog in an inversion layer, the sight enough to send Leslie's knuckle to his mouth. He bit down and tore his gaze away with an effort, turning it on the two alien ships floating overhead.