On the sea the boldest steer but where their ports invite;

But there are wanderers oer Eternity

Whose bark drives on and on,

and anchord neer shall be.

~ Byron:

Childe Harold III.lxx.

This book is about war, and as such it will present some of the dilemmas, uncertainty, brash cruelty and senseless insanity of war. In this cauldron every man reacts differently, some finding the full measure of their courage and compassion, others finding the depths of their cowardice and depravity. One should never be surprised that a loaded gun fires a bullet, and that a bullet kills with no thought given to things like courage and compassion. Given the record of history one thing is wholly apparent: the only way a man can ever truly prevent that loaded gun from firing is to never make one.

As to the ships, planes and men depicted in this novel, while the ship and crew of the Russian battlecruiser Kirov are of my own making, every other ship and character mentioned, from the highest officers on down to the lowest able seaman or pilot, is a historical figure, placed exactly in the roles and locations where they served during the action described.

On a late summer day, August 5, 1941, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt boarded the yacht Potomac and slipped quietly away on what was scheduled to be a fishing trip to the waters off the coast of New England. A day earlier, the Prime Minister of England, Sir Winston Churchill, had declared a Flag Day and quietly canceled official business at the House of Commons to get away for a supposed vacation as well. Yet these were merely cover stories fed to the press to mask planning for a secret meeting that would lay the groundwork for a new power structure in a world that was embroiled in the greatest conflict in human history.

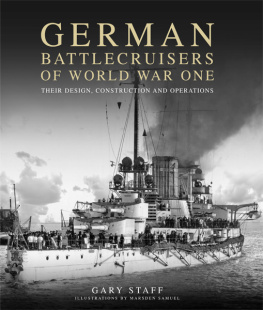

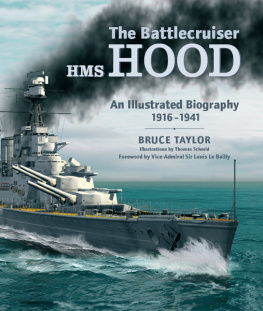

Churchill boarded the destroyer HMS Oribi and traveled to the British Home Fleet anchorage at Scapa Flow where he was discretely transferred to the battleship HMS Prince of Wales. The great ship was the youngest daughter of Britains powerful battle fleet, bloodied as a young debutant when she sailed on the arm of Admiral Hollands flagship HMS Hood, just two months earlier in the hunt for the German Battleship Bismarck. In the engagement that followed, the raw crew aboard the ship struggled in battle with the mighty German battleship, witnessing the horror of the destruction of HMS Hood, with the tragic loss of all but three of her crew.

Prince of Wales had herself sustained damage from at least three 15 inch shells fired by Bismarck and four 8 inch shells from the heavy cruiser Prince Eugen. One shell struck directly on the bridge, killing or wounding everyone except the Captain and Chief Yeoman. The ship was driven off behind a covering screen of smoke, and limped away to Iceland, conducting burials at sea for all those hands lost in the action while in route. Yet, in spite of severe difficulties with her main batteries, she had managed to wound the German ship as well, which continued on into the North Atlantic trailing a wake of black oily blood.

Undaunted, Prince of Wales reached the dockyard at Rosyth for repairs, where astonished engineers soon found an unexploded 15 inch shell lodged well below the waterline near the starboard diesel room, like a sharp tooth of a shark left in the wounded belly of the ship after her harrowing encounter with the Bismarck. She was soon restored to health, patched up and re-armored, her guns dressed out in fresh camouflage paint, and a new type 271 radar mounted on her upper mast. The rest of the Royal Navy ruthlessly hunted down the German battleship, sinking Bismarck on 27 May, 1941, finally avenging the loss of Hood.

Now, her refit complete, Prince of Wales rejoined the home fleet, completed gunnery trials with her sister ship King George V, and was ready for a very special honor. The Prime Minister himself made his way aboard, there to be joined by Admiral of the Fleet and First Sea Lord Sir Dudley Pound, Army General Dill and Vice Air Chief Freeman, all bound for a rendezvous that would lay down the political and geopolitical framework to govern the entire post war world.

They were sailing aboard Prince of Wales to meet their respective American counterparts, for President Roosevelt was not going fishing that morning. Instead he was to be joined by Generals Marshall and Arnold, and Admirals Stark and King of the United States to embark on the heavy cruiser Augusta and sail quietly out of Massachusetts Bay to points unknown. The old battleship Arkansas, heavy cruiser Tuscaloosa, and five more destroyers would join the task force en route for an extra measure of defense.

Prince of Wales raced out into the gray north Atlantic with three destroyers at her side to join the American leaders for a scheduled meeting at Ship Harbor, Argentia Bay, Newfoundland on August 9th, 1941. There they would discuss potential future military cooperation, and set down guiding principles for how the world would be governed by Anglo-American power after Germanys defeat, which at that time seemed a distant and chancy prospect. The document they drafted would come to be called the Atlantic Charter, a series of seminal principles that would underlay the founding of the United Nations.

Yet on that fateful day, and unbeknownst to many, they secretly discussed something more, the dark presence and mystery of a strange new interloper on the wide Atlantic Ocean, a frightening new raider with awesome power and ominous intent.

So long the path; so hard the journey,

When I will return, I cannot say for sure,

Until then the nights will be longer.

Sleep will be full of dark dreams and sorrow,

But do not weep for me

~ Russian Naval Hymn

Admiral Leonid Volsky shifted uncomfortably in his chair as he stared out at the slate gray sea. There was something wrong with the morning, he thought, and something vaguely disturbing about this whole mission. He felt it from the very first, that vague sense of disquiet within him that had dogged his thoughts all morning. What was it?

The mission itself was nothing out of the ordinarya simple live fire exercise in the Norwegian Sea. There had been so many before it, long, dull cruises punctuated by a single moment of bravado when the missiles would catapult up from the forward deck and rocket away, the men cheering them on as they went to find the target barges to the south.

He was waiting on K-266, the submarine Orel, scheduled to make its missile firing at zero eight hundred hours, but Orel was late, and the Admiral had become more and more impatient. The crew could see it in his eyes, dark brown eyes, deep set under bristling low brows. Orel was late, and for a man accustomed to tight schedules, itineraries, precise maneuvers required to coordinate fleet actions, tardiness was inexcusable.

Orel was late because her Captain Rudnikov was fat and stupid, he thought. And Rudnikov was fat and stupid because the aging incompetence of the Russian system itself still permeated the navy these days, and that was the sad fact of the matter.

Leonid Volsky was not happy. He was in his seat on the bridge of the most formidable ship his country had ever put to sea, the nuclear guided missile cruiser Kirov, flagship and pride of the Russian Navy, and he was about to unleash her scheduled missile salvo for the exercise now underway. Thirty kilometers to the south, the old cruiser