Contents

Guide

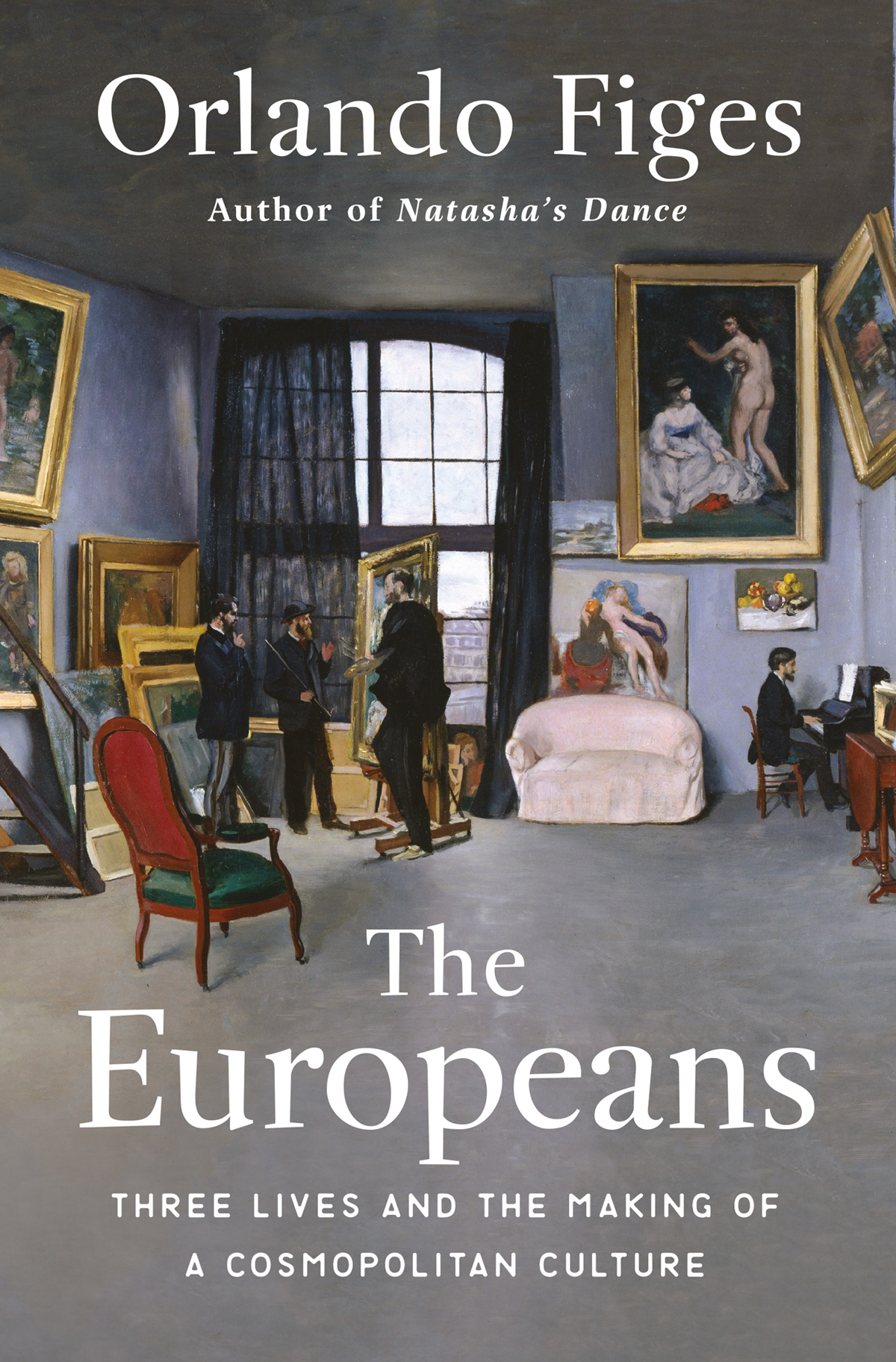

The

Europeans

THREE LIVES AND THE MAKING OF A COSMOPOLITAN CULTURE

Orlando Figes

METROPOLITAN BOOKS

HENRY HOLT AND COMPANY NEW YORK

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: http://us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

For my sister, Kate

When the arts of all countries, with their native qualities, have become accustomed to reciprocal exchanges, the character of art will be enriched everywhere to an incalculable extent, without the genius peculiar to each nation being changed. In this way a European school will be formed in place of the national sects which still divide the great family of artists; then, a universal school, familiar with the world, to which nothing human will be foreign.

Thophile Thor, Des tendances de lart au xixe sicle (1855)

Money has emancipated the writer, money has created modern literature.

mile Zola, Money in Literature (1880)

You are a foreigner of some sort, said Gertrude.

Of some sort yes; I suppose so. But who can say of what sort? I dont think we have ever had occasion to settle the question. You know there are people like that. About their country, their religion, their profession, they cant tell.

Henry James, The Europeans (1878)

I have given monetary figures in their original currencies but have added in parentheses a French-franc equivalent where this may be useful for comparison. The French franc was the currency most widely used in Europe in the nineteenth century, and it was in francs that the people at the centre of this book mostly handled their affairs.

The exchange rates between Europes major currencies remained relatively stable for most of the nineteenth century. They depended on the metal content of the coins. The key stabilizing factor was the British pound, which was on the gold standard. Other currencies established stable exchange rates with the British pound by moving to the silver standard (as did most of the German and Scandinavian states) or the bimetallic (gold and silver) standard (as did France and Russia). From the 1870s there was a general European move towards parity with gold.

In the middle decades of the nineteenth century 100 French francs were worth roughly

| British pounds |

| Russian silver roubles |

| Milanese (Austrian) lire |

| Roman scudi |

| Neapolitan ducats |

| Austrian gulden |

| Prussian thaler |

| Belgian francs |

| US dollars |

As an indicator of value the simple conversion of currencies can be misleading because it fails to take into account differences in purchasing power. The cost of living in Britain was generally higher than on the Continent, although some items (such as cotton) were cheaper because of the benefits of industrialization and empire. Higher costs were reflected in higher wages in Britain too. The British professional classes were paid significantly more than their confrres on the Continent. In 1851, the salary of a British judge in the Court of Appeal was 6,000 (around 150,000 francs), twice the annual income of his French equivalent. The fellow of an Oxford college had a basic income of 600 per year (around 15,000 francs), more than a professor at the Sorbonne earned (around 12,000 francs a year). Lower down the social scale the differential was less significant. A middling British family would generally have an annual income of around 200 (5,000 francs) in the 1850s, an income at least equalled by the vast majority of bourgeois families in France, where dowries continued to supplement the household income more substantially than in Britain. A French mechanic or junior engineer earned anything between 3,000 and 7,000 francs a year. A skilled urban labourer or clerk had an annual salary of anything between 800 francs and 1,500 francs. At this end of the social scale British salaries were similar.

In the arts incomes were extremely variable. In monetary terms the writers, artists and musicians featured in this book were located on the scale described above anywhere between the best-paid judge and the worst-paid mechanic. A few examples must suffice to illustrate the variations in income. At the peak of his career, in the 1850s, the painter Ary Scheffer earned between 45,000 and 160,000 francs per year; but many artists, such as Scheffers protg, Thodore Rousseau, meanwhile made less than 5,000 francs a year. Before 1854, the writer Victor Hugo received from his writings, on average, 20,000 francs per year. George Sand and Ivan Turgenev earned about the same amount the latter getting as much money again from his estates in Russia. Between 1849 and 1853 the composer Robert Schumann earned, on average, around 1,600 Prussian thalers (6,000 francs) from his compositions every year, an income supplemented by his salary as music director in Dsseldorf, which paid 750 thalers (approximately 2,800 francs) per year.

It is almost impossible to translate these figures into todays terms. The cost of goods and services was very different in the nineteenth century. Labour was a lot cheaper (and in Russia free for landowners owning serfs); rent was far less costly too; but food was relatively expensive in the cities. To help readers get a general sense of monetary values in the mid-nineteenth century: a million francs was a large fortune, purchasing goods and services worth around 5,000,000 ($6,500,000) in todays terms; 100,000 francs was enough to buy a chteau with extensive land (such as the one at Courtavenel purchased by the Viardots); while 10,000 francs, worth approximately 50,000 ($65,000) today, was the price the Viardots paid for an organ made by the famous organ-builder Aristide Cavaill-Coll in 1848.

There were two types of rouble in circulation until 1843: the silver rouble (worth then about four French francs), used for foreign payments, and the assignat or paper rouble, which could be exchanged for the silver rouble at a rate of 3.5 to 1. In 1843, the paper rouble was replaced by State credit notes.

ILLUSTRATIONS IN THE TEXT

The Thtre Italien, engraving after a drawing by Eugne Lami, c. 1840. (New York Public Library)

Alfred de Musset, satire on Louis Viardots courtship of Pauline, cartoon, c. 1840. Bibliothque de lInstitut de France, Paris. (Copyright RMN-Grand Palais (Institut de France)/Grard Blot)

Giacomo Meyerbeer, photograph, 1847. (Wikimedia Commons)

Varvara Petrovna Lutovinova, Turgenevs mother, daguerreotype, c. 1845. (I. S. Turgenev State Memorial Museum, Orel)

Clara and Robert Schumann, daguerreotype, c. 1850. (adoc-photos/Getty Images)

The Leipzig Gewandhaus, engraving, c. 1880. (akg-images)

Pauline Viardot, drawing of the chteau at Courtavenel, in a letter to Julius Rietz, 5 July 1858. (New York Public Library (JOE 82-1, 40))

Musical score for Frdric Chopin, Six Mazurkas, arr. Pauline Viardot, E. Grard & Cie, 1866. Private collection.

The skating ballet from Le Prophte