Also by the Author

The Devils Teeth

DOUBLEDAY

Copyright 2010 by Susan Casey

All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Doubleday, a division of Random House, Inc., New York.

www.doubleday.com

www.susancasey.com

DOUBLEDAY and the DD colophon are registered trademarks of Random House, Inc.

Published simultaneously in Canada by Doubleday Canada.

Title page photo erikaeder.com

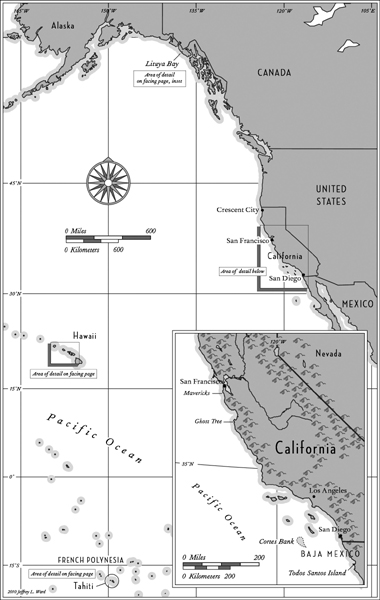

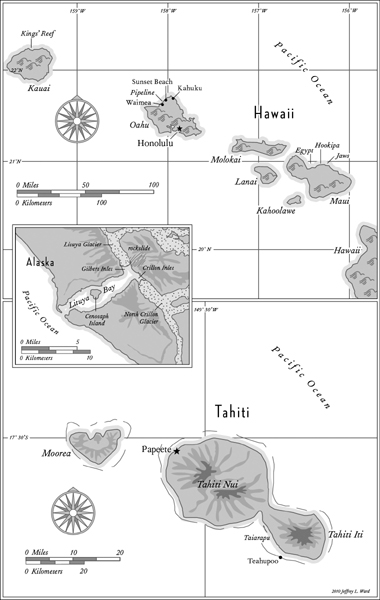

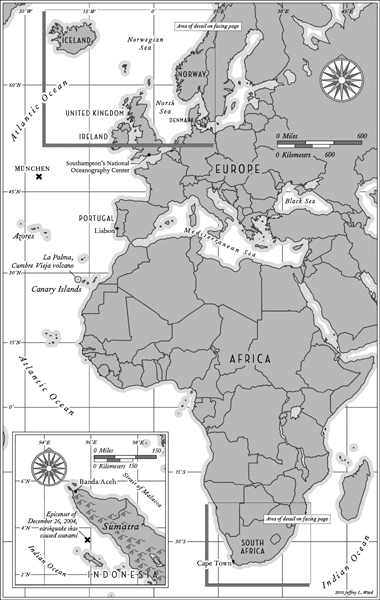

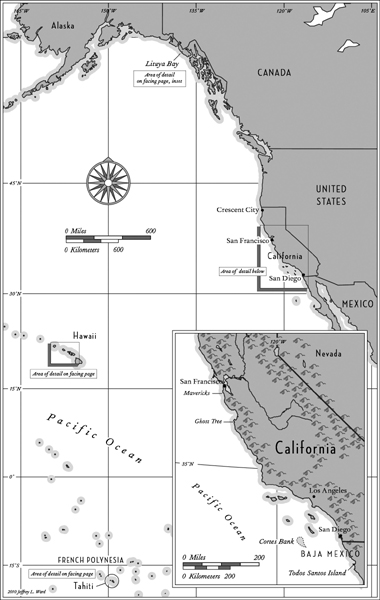

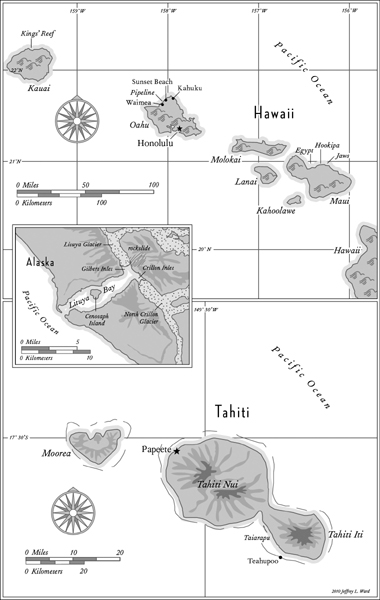

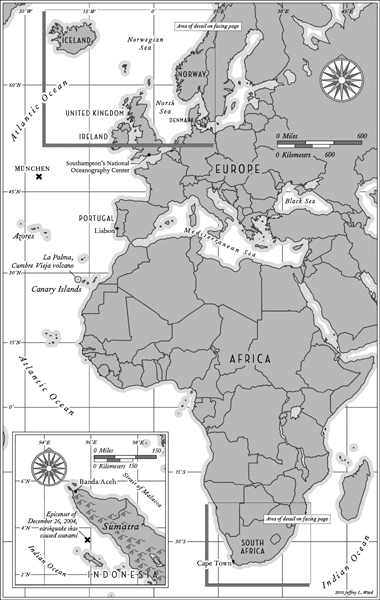

Maps designed by Jeffrey L. Ward

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Casey, Susan, 1962

The wave : in pursuit of the rogues, freaks, and giants of the ocean / by Susan Casey.

p. cm.

1. Rogue waves. I. Title.

GC227.C37 2010

551.463dc22 2010010193

eISBN: 978-0-307-71583-8

v3.1

In memory of my father,

RON CASEY

W HEN YOU LOOK INTO THE ABYSS, THE ABYSS ALSO LOOKS INTO YOU .

Friedrich Nietzsche

CONTENTS

57.5 N, 12.7 W, 175 MILES OFF THE COAST OF SCOTLAND

FEBRUARY 8, 2000

T he clock read midnight when the hundred-foot wave hit the ship, rising from the North Atlantic out of the darkness. Among the oceans terrors a wave this size was the most feared and the least understood, more myth than realityor so people had thought. This giant was certainly real. As the RRS Discovery plunged down into the waves deep trough, it heeled twenty-eight degrees to port, rolled thirty degrees back to starboard, then recovered to face the incoming seas. What chance did they have, the forty-seven scientists and crew aboard this research cruise gone horribly wrong? A series of storms had trapped them in the black void east of Rockall, a volcanic island nicknamed Waveland for the nastiness of its surrounding waters. More than a thousand wrecked ships lay on the seafloor below.

Captain Keith Avery steered his vessel directly into the onslaught, just as hed been doing for the past five days. While weather like this was common in the cranky North Atlantic, these giant waves were unlike anything hed encountered in his thirty years of experience. And worse, they kept rearing up from different directions. Flanking all sides of the 295-foot ship, the crew kept a constant watch to make sure they werent about to be sucker punched by a wave that was sneaking up from behind, or from the sides. No one wanted to be out here right now, but Avery knew their only hope was to remain where they were, with their bow pointed into the waves. Turning around was too risky; if one of these waves caught Discovery broadside, there would be long odds on survival. It takes thirty tons per square meter of force to dent a ship. A breaking hundred-foot wave packs one hundred tons of force per square meter and can tear a ship in half. Above all, Avery had to position Discovery so that it rode over these crests and wasnt crushed beneath them.

He stood barefoot at the helm, the only way he could maintain traction after a refrigerator toppled over, splashing out a slick of milk, juice, and broken glass (no time to clean it upthe waves just kept coming). Up on the bridge everything was amplified, all the night noises and motions, the slamming and the crashing, the elevator-shaft plunges into the troughs, the frantic wind, the swaying and groaning of the ship; and now, as the waves suddenly grew even bigger and meaner and steeper, Avery heard a loud bang coming from Discoverys foredeck. He squinted in the dark to see that the fifty-man lifeboat had partially ripped from its two-inch-thick steel cleats and was pounding against the hull.

Below deck, computers and furniture had been smashed into pieces. The scientists huddled in their cabins nursing bruises, black eyes, and broken ribs. Attempts at rest were pointless. They heard the noises too; they rode the free falls and the sickening barrel rolls; and they worried about the fact that a six-foot-long window next to their lab had already shattered from the twisting. Discovery was almost forty years old, and recently shed undergone major surgery. The ship had been cut in half, lengthened by thirty-three feet, and then welded back together. Would the joints hold? No one really knew. No one had ever been in conditions like these.

One of the two chief scientists, Penny Holliday, watched as a chair skidded out from under her desk, swung into the air, and crashed onto her bunk. Holliday, fine boned, porcelain-doll pretty, and as tough as any man on board the ship, had sent an e-mail to her boyfriend, Craig Harris, earlier in the day. This isnt funny anymore, she wrote. The ocean justlooks completely out of control. So much white spray was whipping off the waves that she had the strange impression of being in a blizzard. This was Waveland all right, an otherworldly place of constant motion that took you nowhere but up and down; where there was no sleep, no comfort, no connection to land, and where human eyes and stomachs struggled to adapt, and failed.

Ten days ago Discovery had left port in Southampton, England, on what Holliday had hoped would be a typical three-week trip to Iceland and back (punctuated by a little seasickness perhaps, but nothing major). Along the way theyd stop and sample the water for salinity, temperature, oxygen, and other nutrients. From these tests the scientists would draw a picture of what was happening out there, how the oceans basic characteristics were shifting, and why.

These are not small questions on a planet that is 71 percent covered in salt water. As the Earths climate changesas the inner atmosphere becomes warmer, as the winds increase, as the oceans heat upwhat does all this mean for us? Trouble, most likely, and Holliday and her colleagues were in the business of finding out how much and what kind. It was deeply frustrating for them to be lashed to their bunks rather than out on the deck lowering their instruments. No one was thinking about Iceland anymore.

The trip was far from a loss, however. During the endless trains of massive waves, Discovery itself was collecting data that would lead to a chilling revelation. The ship was ringed with instruments; everything that happened out there was being precisely measured, the seas fury captured in tight graphs and unassailable numbers. Months later, long after Avery had returned everyone safely to the Southampton docks, when Holliday began to analyze these figures, she would discover that the waves they had experienced were the largest ever scientifically recorded in the open ocean. The significant wave height, an average of the largest 33 percent of the waves, was sixty-one feet, with frequent spikes far beyond that. At the same time, none of the state-of-the-art weather forecasts and wave modelsthe information upon which all ships, oil rigs, fisheries, and passenger boats relyhad predicted these behemoths. In other words, under this particular set of weather conditions, waves this size should not have existed. And yet they did.