THE DUEL

THE DUEL

The Eighty-Day Struggle Between

CHURCHILL AND HITLER

JOHN LUKACS

Yale University Press paperback edition first published in 2001.

Cloth edition published 1990 by Ticknor & Fields.

Copyright 1990 by John Lukacs

All rights reserved

This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publishers.

Printed in the United States of America

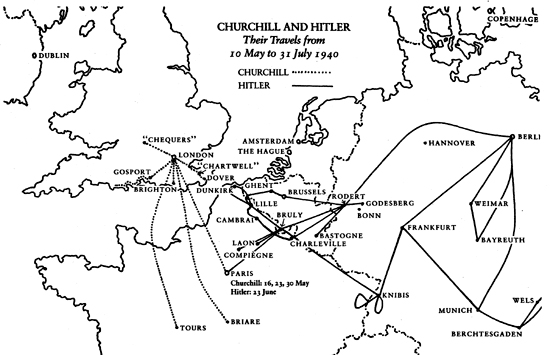

Map by Charles P. Segal

Library of Congress catalog card number: 00-108628

ISBN 978-0-300-08916-5 (pbk.)

A catalog record for this book is available from the British Library.

10 9 8 7 6

To the memory of

BRIGADIER CLAUDE NICHOLSON,

defender of British honor at Calais

and

ADAM VON TROTT ZU SOLZ,

defender of German honor in Berlin

The sociologist, etc., deals with his material as if the outcome were given in the known facts: he simply searches for the way in which the result was already determined in the facts. The historian, on the other hand, must always maintain towards his subject an indeterminist point of view. He must constantly put himself at a point in the past at which the known factors still seem to permit different outcomes. If he speaks of Salamis, then it must be as if the Persians might still win.

Johan Huizinga, The Idea of History

CONTENTS

THE DUEL

I

THE EIGHTY DAYS DUEL

IN THE YEAR 1940 Easter fell very early. This meant that Pentecost would come early too, Whitsunday on the twelfth of May. In England and Europe this was a two-day holiday.

On the tenth of May, a Friday, all over Western Europe the night was clear and starry, presaging a beautiful spring day. In the first hour of that day an unusual train, pulled by two great steam engines, consisting of ten exceptionally long dark green coaches, slid to a halt at a switch near Hagenow station, on the long straight track between Hannover and Hamburg. This was the special train with the special carriages built for Adolf Hitler and his entourage, massive, dark and sleek, one of the impressive instruments of the Third Reich, made of the best German steel. Its code name was Amerika.

A few minutes after midnight, Western European time, this train changed course, so efficiently and silently that hardly any of its occupants woke to notice that it began to move again, and in a direction different from its earlier one. It had been going northward. Its occupants had not been told where to; the destination seemed to be Hamburg. Most of them thought that the Fhrer was off to Norway, most of which country had been conquered by his forces during the previous three weeks. He himself had made an oblique remark to that effect to one of his female secretaries. Now, at one in the morning, Berlin time (German clocks had been set forward an hour when the war had begun), the great train started steaming to the west.

Four hours later it hissed to a stop. The insides of those amply armored and paneled carriages were awake with the muffled stirring that is the matutinal sound in all sleeping cars. Their inhabitants pulled up their shades; they glimpsed a station building that had no nameplate. All nameplates had been removed. What they could see all around were the yellow signs and markers of the German Wehrmacht. Presently they learned that they were in Euskirchen, a small German town between Bonn and Aachen, close to the Belgian frontier. Then they were driven to a group of barracks up the hill from the village of Rodert in the Mnstereifel. That would be their spartan headquarters for the next twenty-three days, in a forest clearing that many of them would recall with pleasure because of the many trees and the endless variety of birds chirping and twittering. Its code name was Felsennest, the Rock Eyrie.

The Chef (this was how his staff referred to Hitler) was fresh, determined, nervous. His appearance at that hour was quite unusual for him. His habit was to stay up late. Customarily he would not rise and make his toilet until after eleven. He made a gesture to his staff, who quickly gathered around him, eager to hear what the Fhrer was about to say. Gentlemen, he said, the offensive against the Western Powers has begun. Immediately they could hear from the distance the damp thudding of artillery. Forest, birdsong and gunfire: in that great German dawn hour it was bliss to be alive.

The greatest adventure in Adolf Hitlers career had now started. It would gather speed at a rate unimagined by anyone, including himself. In less than forty days he would be the master of Europe, perhaps of most of the world. His new German flag would fly from the North Cape to the Pyrenees. His armies would conquer Western Europe at a cost of men and equipment that was less than what the German imperial army had spent at a comparable time for the sake of a few miles across the trenches in World War I.

Much of this would be the result of military decisions that he, Hitler, had made. Twenty years before, after he had decided to become a politician, people dismissed him: how could this untutored outsider be the leader of a German political party of importance? He fooled them; he proved that he was a master at German national politics; he won. He became the German chancellor, and people again underestimated him: what could this demagogue, with his provincial mind, know about diplomacy and Europe? He fooled them; he proved to be a formidable statesman; in six years he made Germany greater than Bismarck had ever done, and he achieved all of that without war. People now said: A war? What kind of a war? With a Germany bereft of the kind of navy, colonies, materials and the assets that Imperial Germany had had in 1914? He fooled them again. In May 1940 the strategy of the Western European campaign had been selected by Hitler the plan to strike through the Ardennes, to fool the Allies, to make straight for the English Channel. It was a plan of genius.

Napoleon once said that in war, as in prostitution, amateurs are often better than professionals. Hitler may have been an amateur at generalship, but he possessed the great professional talent applicable to all human affairs: an understanding of human nature and the understanding of the weaknesses of his opponents. That was enough to carry him very far.

Very far. He would sweep away the French and force the British out of Europe. Then he would lay down his terms of peace to the British that they would have to accept.

He was almost sure of these matters on that sunlit, bird-twittering day of the tenth of May. Almost, but not quite. He was nervous, too: anxious whether the plans for the main army group would work; anxious about the weather; aware that the decisive news about his plan, Sichelschnitt, the sickle-cut slice leftward across northernmost France, trapping the French and British armies in Belgium, would not be at hand for a few days yet. However, all seemed to go well that day. When the late May evening fell, he and his staff already felt at home, unpacked and ensconced in the Rock Eyrie. He had a short meeting in the small map room before retiring unusually early (but then he had been up unusually early). Before that he read, among the various news dispatches from the outside world, brought and arranged for him by Walther Hewel, his Foreign Minister Joachim von Ribbentrops liaison man in his headquarters, that across the Channel Winston Churchill had become the prime minister of England.

Next page