One of our men opened up on the NVA at about the same time they began firing at us. It was that fast. They were on both sides of us, and the volume of fire was terrific. When they opened up on the team, I was in a kneeling position and immediately began firing back. Suddenly, I felt a round strike me in the chest. It sent me twisting to my left, and as I turned back into my original position, I reached over to grab my knife out of its scabbard, only to discover that I now had half a knife. The bullet that hit me had gone through the day-night flare that was taped to the sheath of the K-bar, which was positioned upside down on my shoulder harness for quick release. The bullet had broken the steel blade of my knife in two. The NVA were still firing at me, and I remember wondering how in the hell had I broken my K-bar. That was before I realized that all of my teammates had been hit and were dead.

STINGRAY

Also by Bruce H. Norton

Force Recon Diary, 1969

Force Recon Diary, 1970

Encyclopedia Of American War Heroes

With Donald N. Hamblen:

One Tough Marine

With Maurice J. Jacques:

Sergeant Major, U.S. Marines

With Len Maffioli:

Grown Gray In War

With Charles R. Jackson:

I Am Alive

STINGRAY

Force Recon Marines Behind Enemy Lines in Vietnam

Edited by

Major Bruce H. Norton, USMC (Ret.)

Stingray

Quadrant Books

Published by arrangement with the author.

Copyright 2000 by Bruce H. Norton

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, scanned, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical (including photocopying, recording, or information storage and retrieval) without permission in writing from the publisher. For information please contact: or by writing us at the following address:

Endpapers Press

PMB 212

4653 Carmel Mountain Road, STE 308

San Diego, CA 92130-6650

eISBN: 978-1-937868-05-5

Cover design by Aryo Jonk Pambudi.

Visit our website at:

www.endpaperspress.com

Most of the material in this publication is comprised of documents found in U.S. Marines in Vietnam, a series of books compiled by the History and Museums Division Headquarters of the United States Marine Corps.

Quadrant Books are published by Endpapers Press,

a division of Author Coach, LLC

The Quadrant Books logo featuring a Q in the form of a compass is a trademark of Author Coach, LLC.

To Bruce and Elizabeth

Contents

Successful Stingray operations require a complex blend of dedicated assets, which consist of thoroughly knowledgeable planners, commanders, support personnel, and, most important, highly trained reconnaissance elements capable of operating in a fast-reaction target acquisition and destruction mode. Communications and rapid response must be totally reliable and immediate. Anything less is to court disaster.

LT. COL. C. C. COFFMAN JR., USMC (Ret. 1998)

Introduction

Noted Marine Corps historian and author, Allan R. Millet, defined reconnaissance and its importance:

From time immemorial military commanders have been concerned with the availability of timely, useful information during a campaign, especially when they are operating in foreign lands and distant waters. Reconnaissance, the French military term for information gathering, entered the English military vocabulary in the seventeenth century. This standing function of the exercise of command has been performed as long as armies and navies have existed.

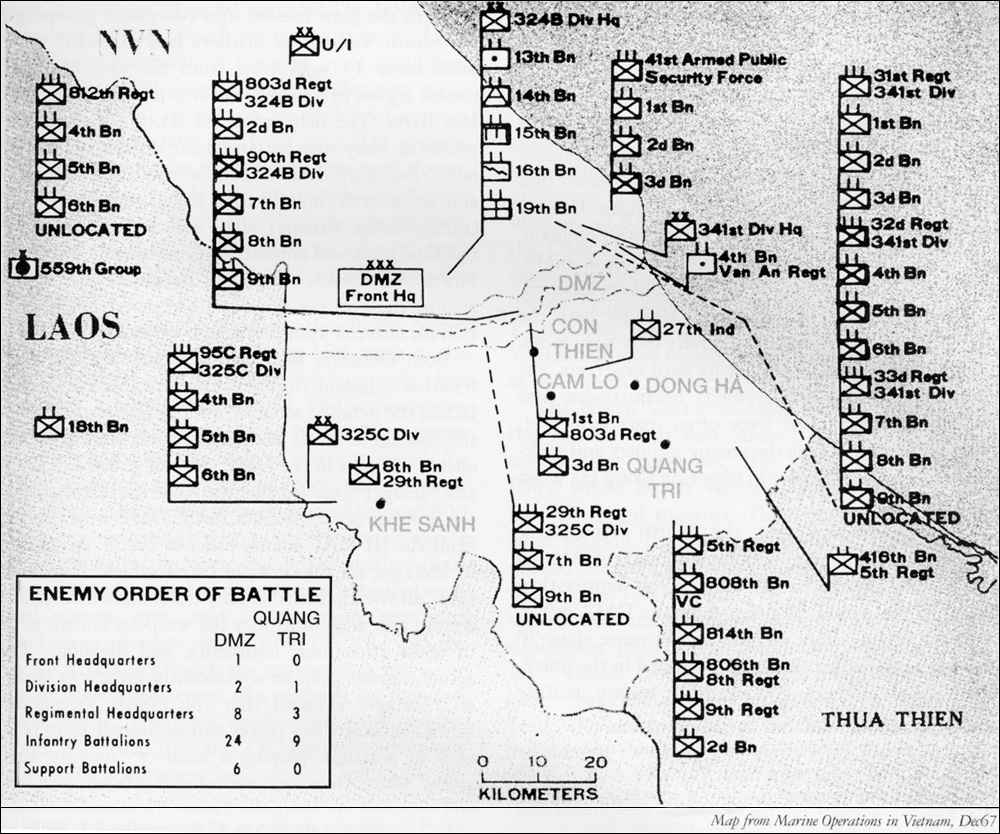

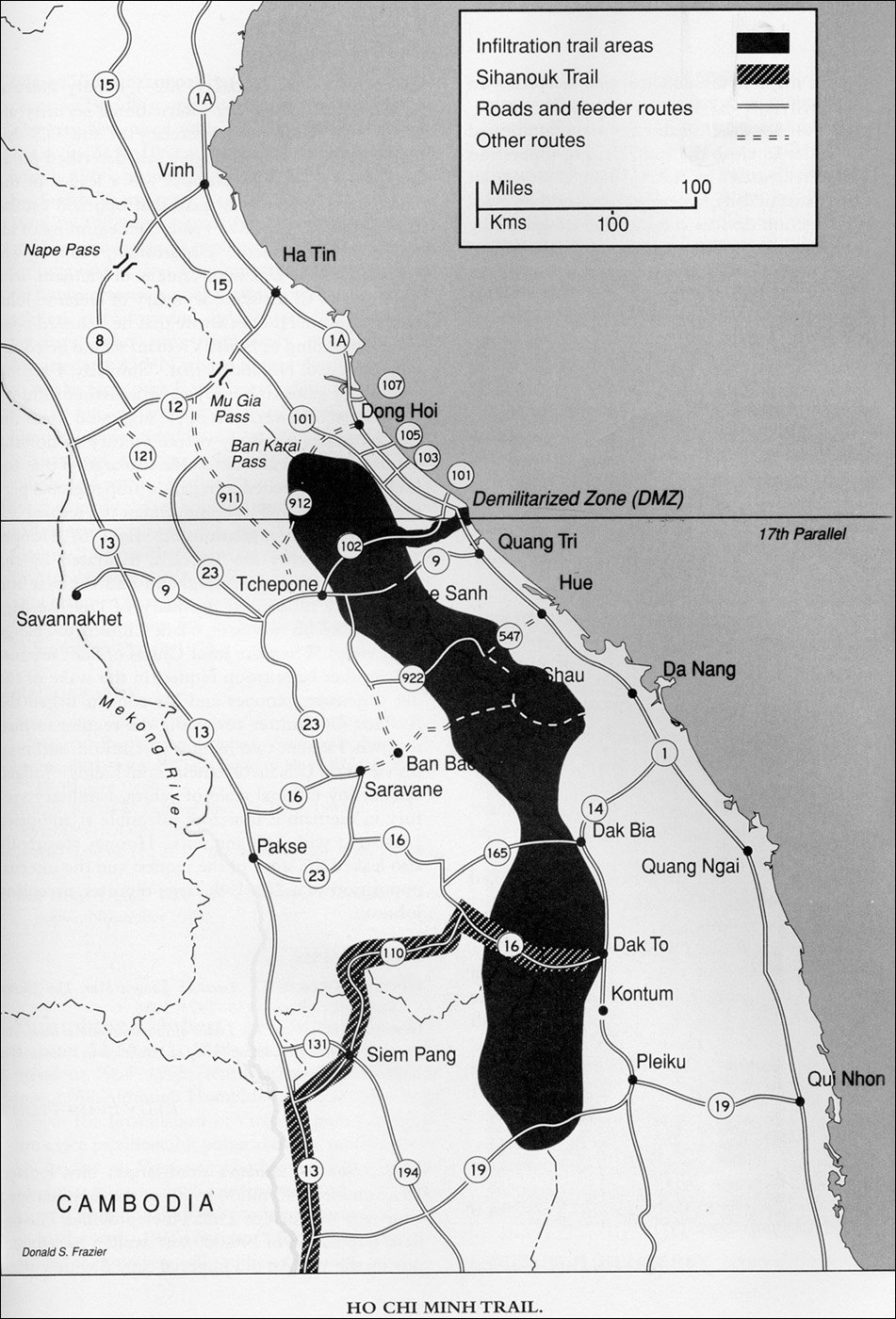

Reconnaissance activities generally focus upon two categories of information: data on terrain and weather, and data about the enemy order of battle and activities. For environmental information, reconnaissance units would gather data on road conditions, bridges, tunnels, passes, civilian and military structures of all types, soil trafficability, economical resources, potable water, obstacles, and significant terrain features such as lakes, mountains, forests, and deserts. Data for naval operations included wind and tide information, weather conditions, and the location of harbors and anchorages, as well as shoal waters and all types of landfall information.

Skilled reconnaissance should also offer details about the enemy, provided that enemy forces are within reach of the means of information gathering. An enemys observable units and their activities can furnish data on strength, force structure, general weapons and equipment, logistical arrangements, patterns of activity in camp or on the march, deployment for battle, and security operations. The one thing reconnaissance observation cannot produce with confidence is insight concerning enemy intentions and plansunless a reconnaissance unit captures knowledgeable prisoners or enemy documents and maps.

The instruments of reconnaissance have changed, even if its purposes have not. Stealth and established observation posts (usually found on hills) favored the foot observer; coverage of wide areas and the rapid delivery of information required mounted scouts or rangers. Skilled armies combined both types of reconnaissance units. By the nineteenth century, however, light cavalry, accompanied by staff officers, performed the core reconnaissance functions. The maritime equivalent of light cavalry was the patrol boat and light or scout cruiser, built for range and speed, not fighting ability.

The revolution in transportation and communications technology in the twentieth century expanded the capabilities of reconnaissance forces in geographic coverage, the recording of information, and the transmission of data to intelligence staffs. By the time of World War II, Army reconnaissance units could be deployed in motorcycles, scout cars, and light-armored fighting vehicles; light aircraft put observers above and beyond the battlefield. Radios allowed observers to report data without returning to command centers. Aerial photography made its debut in World War I. Allied and German photoreconnaissance aircraft produced overhead and oblique aerial photographs of ever-increasing resolution, and photo interpretation entered the repertoire of the intelligence staff. Electronic reconnaissance became possible first by producing sound-gathering devices that provided range and direction information about enemy artillery, and then by recording the direction and content of enemy radio communications. Nowadays, whole families of satellites can take and transmit photographs, record electronic transmissions, and map the world with radar and infrared sensors and the digital reconstruction of elevations and depressions. The vast menu of technical means of data collection has almost swamped the ability of military staffs to analyze information, which, in turn, places an ever-increasing demand upon computerized data storage, analysis, and retrieval. In the field, reconnaissance elements have the advantage of night-vision devices, sensors, and satellite-linked radios that can be integrated with maps and global positioning systems to determine ones position anywhere on earth in terms of latitude and longitude.

Next page