Table of Contents

Pagebreaks of the print version

Guide

Final Journey

The Fate of the Jews in Nazi Europe

Martin Gilbert

Final Journey: The Fate of the Jews in Nazi Europe

Copyright 1979 by Martin Gilbert

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote brief passages in a review.

Electronic edition published 2015 by RosettaBooks

Cover design by Brehanna Ramirez

Cover image of the railway lines coming into Auschwitz-Birkenau 1980 by Martin Gilbert

ISBN (EPUB): 9780795346835

ISBN (Kindle): 9780795346842

www.RosettaBooks.com

The stories told in these pages are based on eye-witness accounts and on contemporary evidence. Wherever possible, I have given the precise date of every document quoted and have cited the actual words used at the time, both by the Nazis and by their victims.

I have tried to tell the stories of individuals, as well as of communities. On their own, the statistics are powerful and terrible. But the story of the Nazi attempt to murder the Jews of Europe concerned individual people; people with names, families, careers and futures, for millions of whom no one survived to mourn, or to remember.

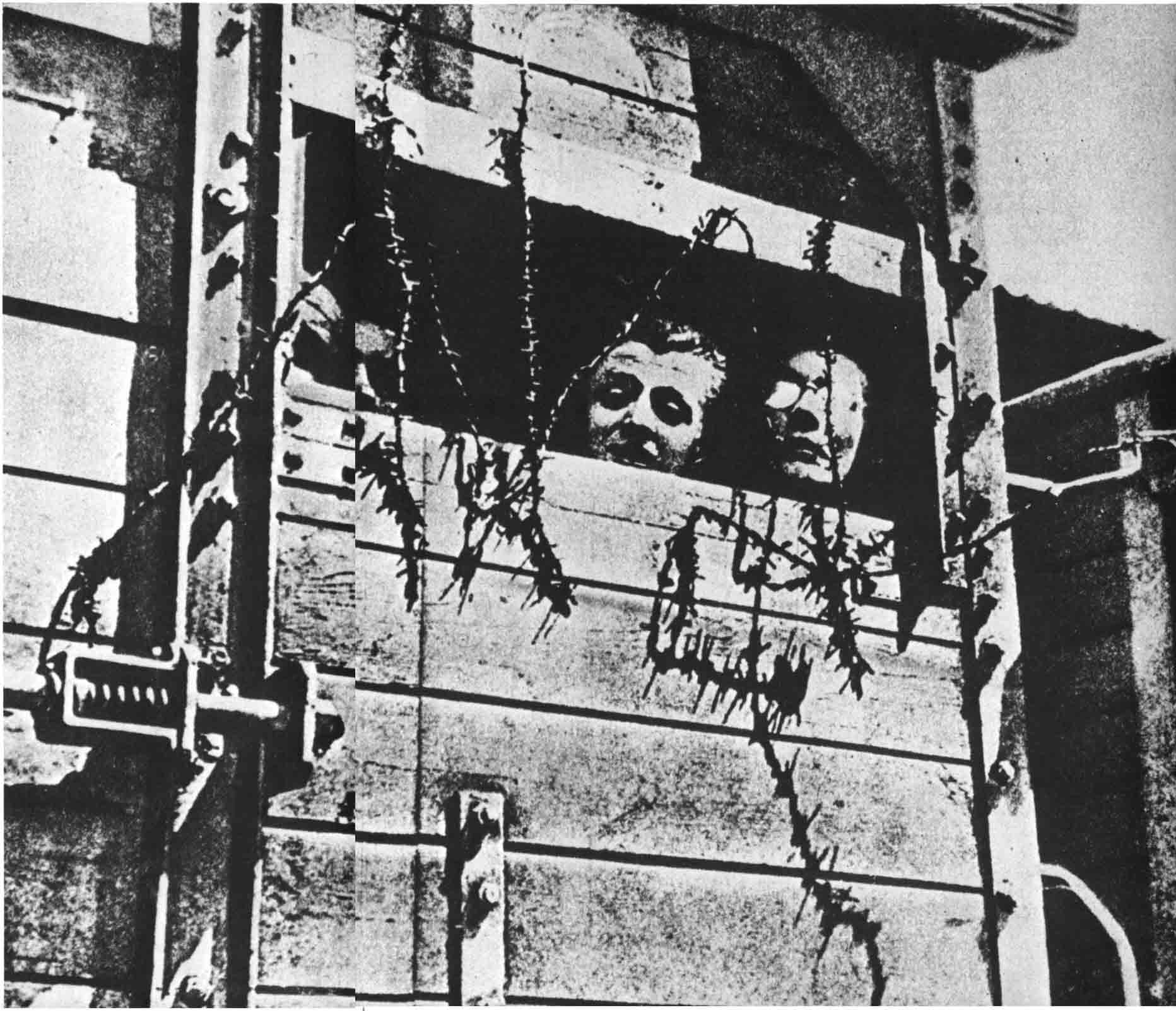

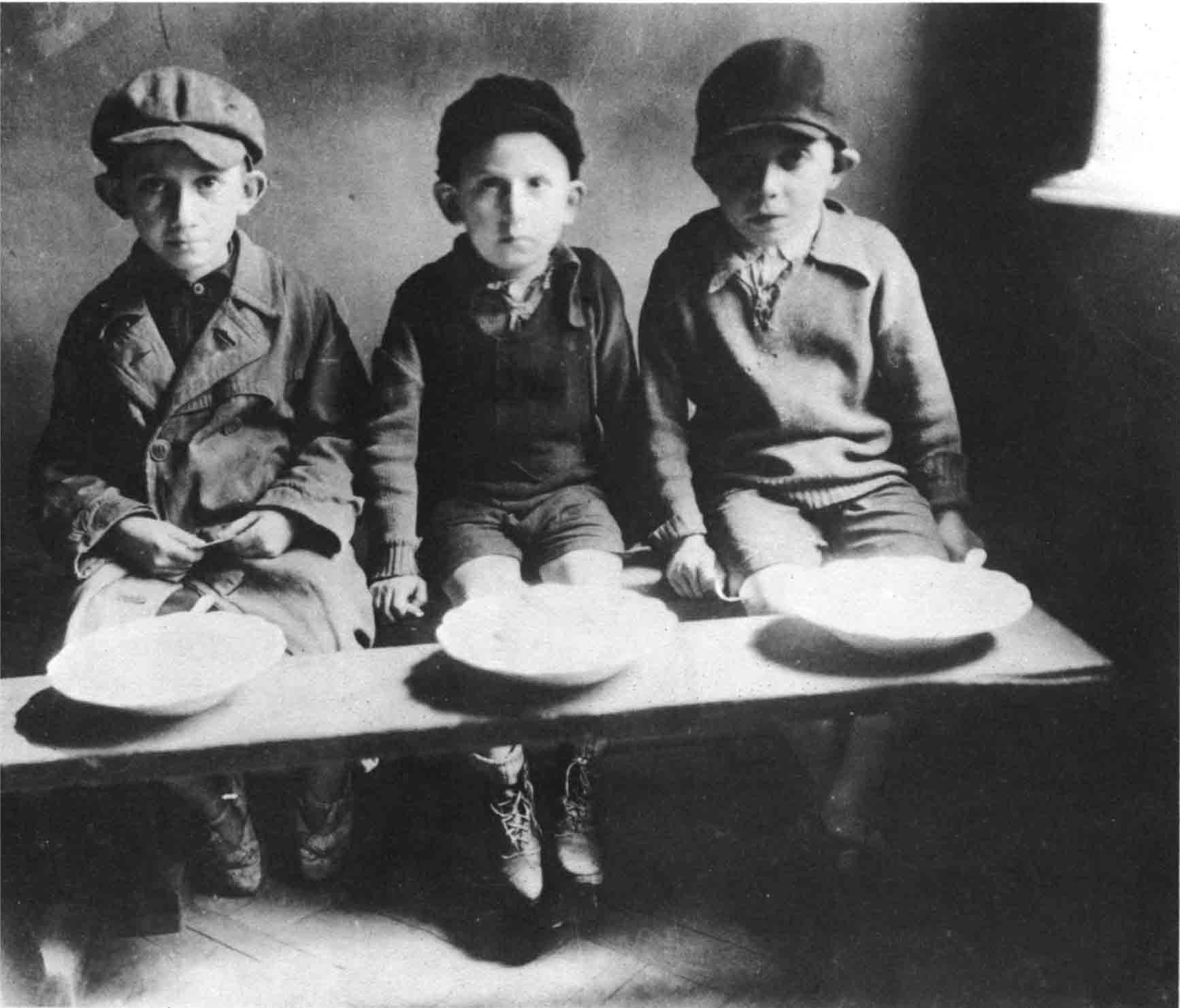

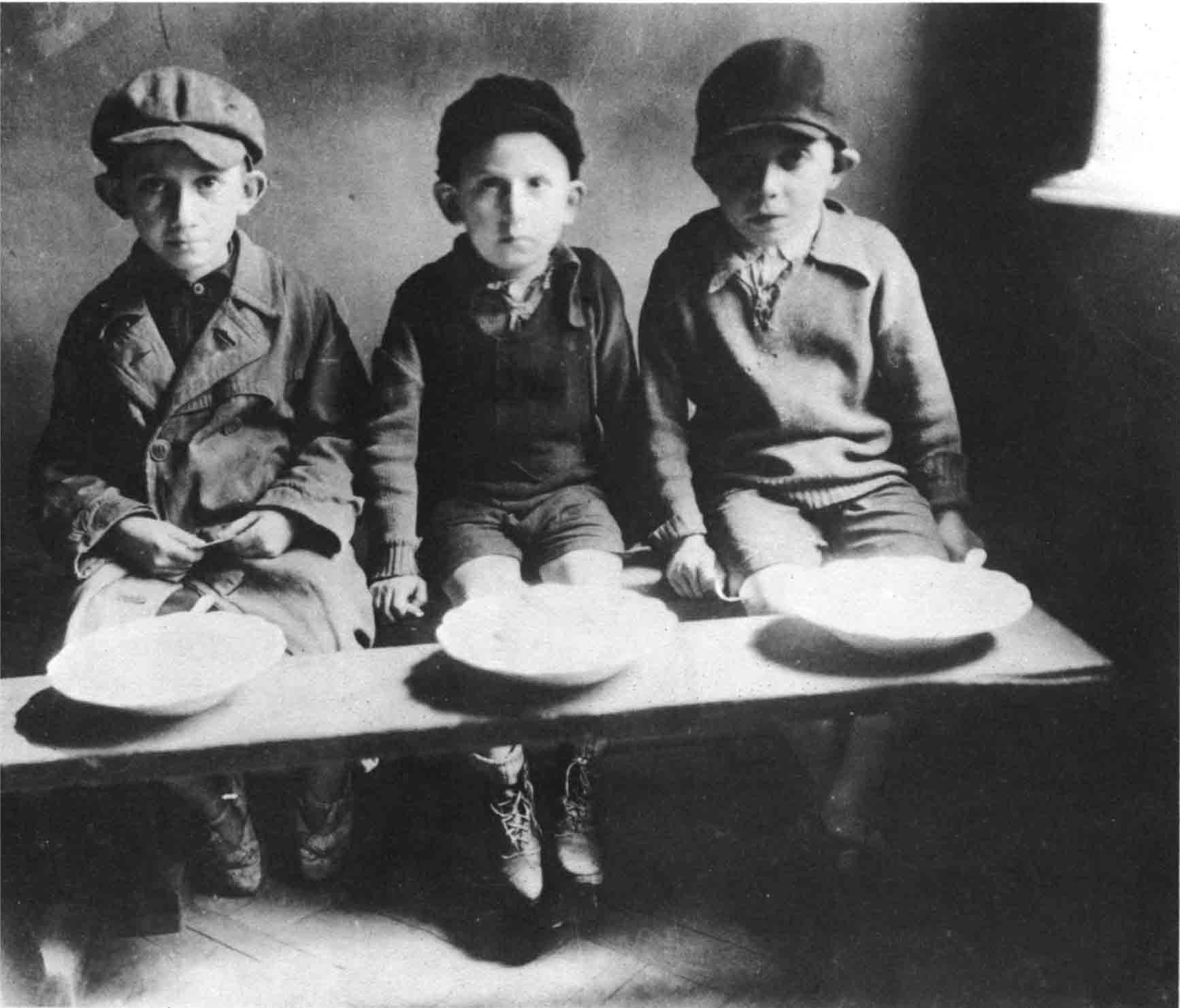

Three children in the Warsaw ghetto. This photograph was taken in 1941 by a Jewish photographer, Mr Forbert. A year later, both he and those whom he photographed were deported eastwards, to the death camp at Treblinka, where they were murdered, together with more than 300,000 Warsaw Jews.

1

Germany, the Jews, and the First Deportations

It has been calculated that more than twenty-five million civilians were killed during the Second World War: murdered in cold blood, with no chance of defending themselves; men, women, children, the sick and the elderly, cripples and babies. Of these twenty-five million, who included Russians, Chinese, Poles, Czechs, Serbs, Greeks, Belgians, Dutchmen, Frenchmen and Gipsies, six million were Jews.

The Jews of Europe had always known anti-semitism, and were no strangers to persecution, massacre and expulsion. Even the opening years of the twentieth century had been painful ones for them in many countries. Before the First World War, attacks, beatings and discrimination had dominated Jewish life in Tsarist Russia, the home of more than four million Jews, while anti-semitic political parties, literature and public outbursts were all too frequent in countries as civilized as France, as recently independent as Rumania, as familiar with minority groups as Austria-Hungary.

After the First World War, anti-Jewish violence had broken out again in Europe, driving many Jews to emigrate to the United States and to Palestine. In the Ukraine more than 80,000 Jews had been massacred during 1919 and 1920, while anti-Jewish attitudes and policies flourished in several of the newly independent, or enlarged States of inter-war Europe, among them Poland, Hungary, Rumania and the Baltic States. But it was in Germany, where more than half a million Jews formed an integral part of one of Europes most modern societies, that hatred of the Jew was not only at its most violent, but became a part of the official policy of the State.

When, on 30 January 1933, Adolf Hitler became Chancellor of Germany, it was a turning point not only for the half million Jews of Germany, but for the seven or eight million Jews who lived elsewhere on the continent of Europe, the descendants of ancient Jewish communities, many of them dating back to Roman times; communities made up of hundreds of thousands of loyal citizens, of patriots, and of many who had submerged their Jewishness into the national life around them.

Hitler was determined to destroy all this, to isolate the Jews, to impoverish them and to drive them outside the daily life, first of Germany and then of Europe. He expressed his deep hatred of the Jews in every speech, and by his speeches stirred the hatred of others, both inside and outside the German Reich.

By a series of laws, beginning in 1933 and culminating two years later in the Nuremberg Laws of 1935, the Jews were driven from German public life and denied all the rights and protections of citizenship.

Among the earliest of these laws was one of 7 April 1933 which forced the compulsory retirement of all non-Aryans from professional life. By a further decree of 11 April 1933, a non-Aryan was defined as anyone with Jewish parents, or with a single Jewish grandparent. Concentration camps were established, in which Jews were among those imprisoned, beaten, terrorized and murdered. Anti-Jewish schoolbooks were published and Jewish children were forced to sit on separate benches at school.

Since the achievement of German unity in 1870, the Jews of Germany had been loyal and valuable citizens. In the days of the Kaiser they had contributed substantially to the prosperity, the culture and the welfare of the Empire. During the First World War 100,000 of them had served in the German army, and, among these, many had won the highest awards for courage. Twelve thousand had died on the field of battle. After the war the Jews had suffered, with their fellow citizens, all the rigours of inflation and economic chaos. In the fourteen years of the Weimar Republic, assimilation was widespread: by 1927 more than 44 per cent of all Jewish marriages were with non-Jews, and at least 1,000 Jews a year either converted to Christianity, or dissociated themselves from the community. The urge to be exemplary citizens was strong in them. But none of this counted against the vitriolic hatred which Nazism now aroused.

No Jew could escape the Nazi determination to drive the Jews from German life, and to make them suffer in the process. Neither assimilation nor conversion could act as a shield. The story of one Jewess is typical of many. Bertha Pappenheim was seventy-five years old when Hitler came to power. Her life had been devoted to the cause of German orphans and delinquent women. Since 1895 she had been a pioneer of womens social welfare. A prominent Jewess, she was strongly and openly opposed to Zionism. After 1933 she spoke out against the emigration of Jews from Germany, fearing the disruption of Jewish family life. But in 1936, aged seventy-eight, she was taken by the Gestapo for questioning, and died as a result of her interrogation.

Neither quality of past service, nor respected position in society; neither ability nor age, could protect a Jew in Nazi Germany. Everywhere, schoolchildren were taught that the Jewish people in their midst were the enemies of Germany. Villages competed with each other to declare themselves Jew-free. Young men in uniform sang the new patriot songs, in which race hatred predominated. One of the most popular of these songs proclaimed: When Jewish blood spurts from the knife, Then all goes twice as well!

By the beginning of 1938, more than 200,000 German Jews had managed to find refuge elsewhere in Europe, some in France, Belgium, Holland, Austria and Czechoslovakia. Others had gone outside continental Europe altogether, to Britain, Palestine and the United States. But as the number of refugees rose each year, country after country began to restrict the numbers of those to whom it would grant admission.