Pagebreaks of the print version

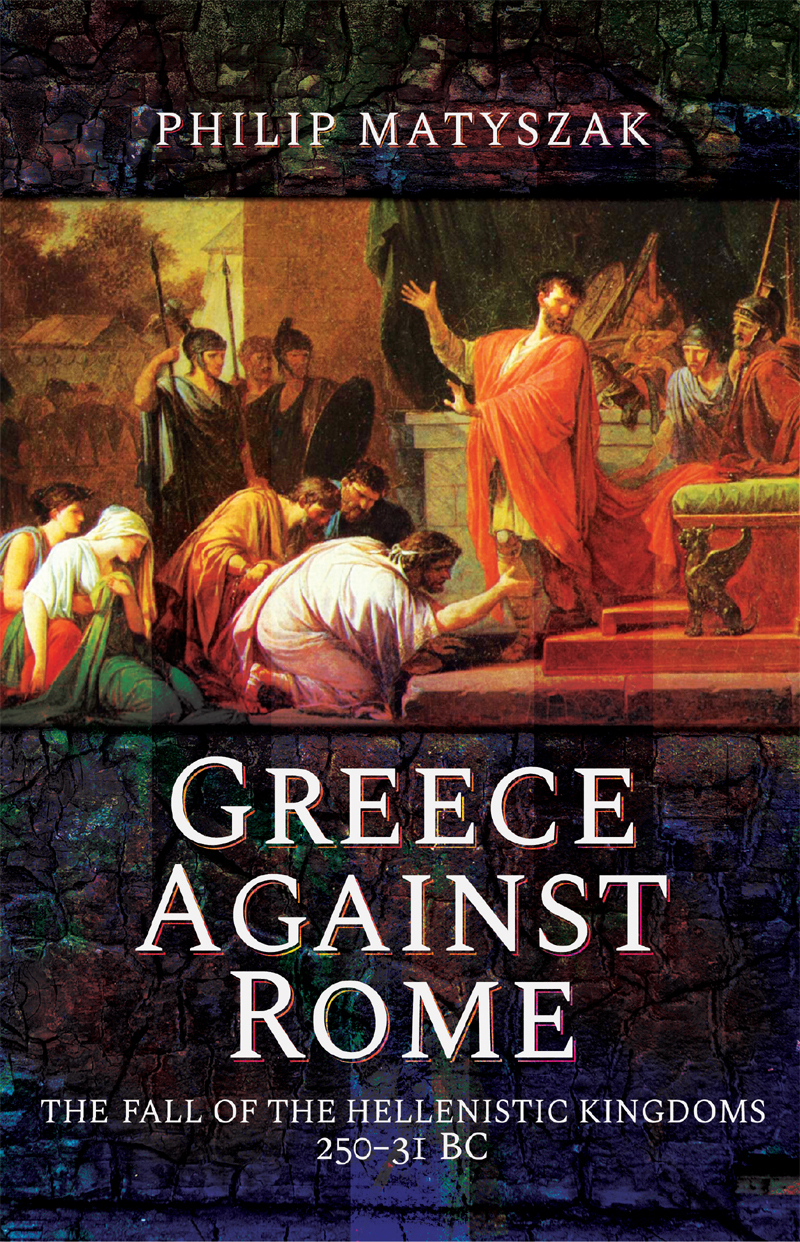

Greece Against Rome

Greece Against Rome

The Fall of the Hellenistic Kingdoms 25031 BC

Philip Matyszak

First published in Great Britain in 2020 by

Pen & Sword Military

An imprint of

Pen & Sword Books Ltd

Yorkshire Philadelphia

Copyright Philip Matyszak 2020

ISBN 978 1 47387 480 0

eISBN 978 1 47387 482 4

Mobi ISBN 978 1 47387 481 7

The right of Philip Matyszak to be identified as Author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the Publisher in writing.

Pen & Sword Books Limited incorporates the imprints of Atlas, Archaeology, Aviation, Discovery, Family History, Fiction, History, Maritime, Military, Military Classics, Politics, Select, Transport, True Crime, Air World, Frontline Publishing, Leo Cooper, Remember When, Seaforth Publishing, The Praetorian Press, Wharncliffe Local History, Wharncliffe Transport, Wharncliffe True Crime and White Owl.

For a complete list of Pen & Sword titles please contact

PEN & SWORD BOOKS LIMITED

47 Church Street, Barnsley, South Yorkshire, S70 2AS, England

E-mail:

Website: www.pen-and-sword.co.uk

Or

PEN AND SWORD BOOKS

1950 Lawrence Rd, Havertown, PA 19083, USA

E-mail:

Website: www.penandswordbooks.com

List of Plates

Marble head possibly depicting a Ptolemaic queen of the period 270250 BC . ( Picture from the Metropolitan Museum, NY )

The god Osiris depicted in classical Egyptian style from the Ptolemaic era. ( Picture from the Metropolitan Museum, NY )

War elephants as depicted in a nineteenth century woodcut. ( Public domain picture )

Antiochus III the Great. ( From a bust in the Louvre, Paris )

Parthian coin of the Hellenistic era. ( Public domain picture )

Apamea on the Orontes. Named after the wife of Seleucus I, this became a major city under later Seleucid kings. ( Creative commons license 1.2 Bernard Gagnon )

Head of an Ethiopian showing how both the Egyptian and Greek elements of the upper classes in Egypt subscribed to Hellenistic conventions of sculpture.

Ptolemy IV Philopater 221204 BC . ( Contemporary coin )

Bronze statuette of a veiled dancer from the Hellenistic era. ( Picture from the Metropolitan Museum NY )

Hellenistic portrayal of a Bactrian camel. ( Picture from the Metropolitan Museum, NY )

Part of the Rosetta Stone, with hieroglyphics at the top. ( Public domain photograph )

Nabis, last king of Sparta 207192 BC . ( From a coin of c.200 BC )

The tomb of Archimedes in Syracuse as imagined by the German artist Carl Rottmann (17971850).

The goddess Cybele on her chariot. ( P. Matyszak )

The theatre in Syracuse. ( Jeremy Day )

Merchant ship of the classical era. ( P. Matyszak )

Cornelius Sulla, 13878 BC . ( P. Matyszak )

Gnaeus Pompeius Magnus Pompey the Great. ( P. Matyszak )

Officer of the Roman army. ( From a bas-relief in the Louvre, Paris )

A Hellenistic statuette of a seated man with his head on his knees. ( Metropolitan Museum, NY )

The death of Cleopatra painted following the description by the biographer Plutarch. ( Jean-Baptiste Regnault, c.17831829 )

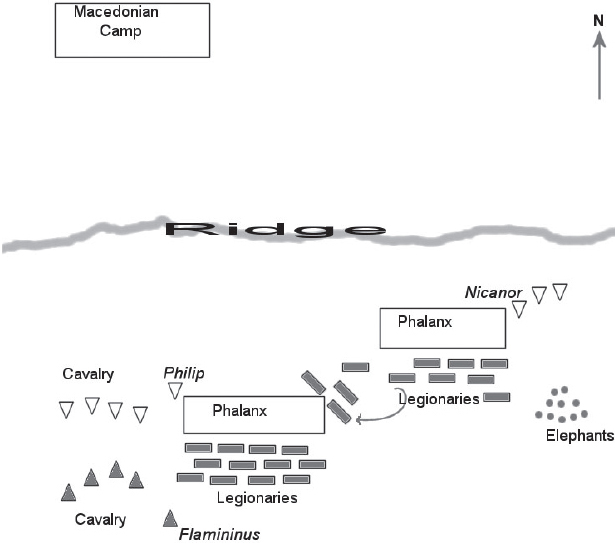

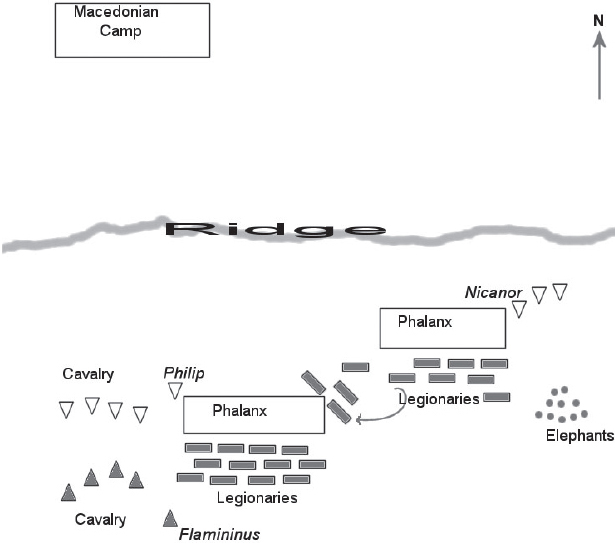

Cynoscephalae 197 BC , at the moment the advancing Romans were able to attack the more rigid Macedonian phalanx.

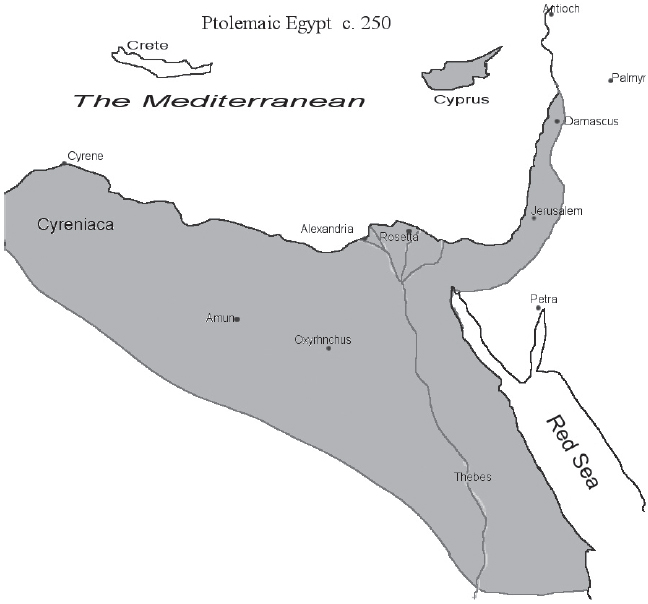

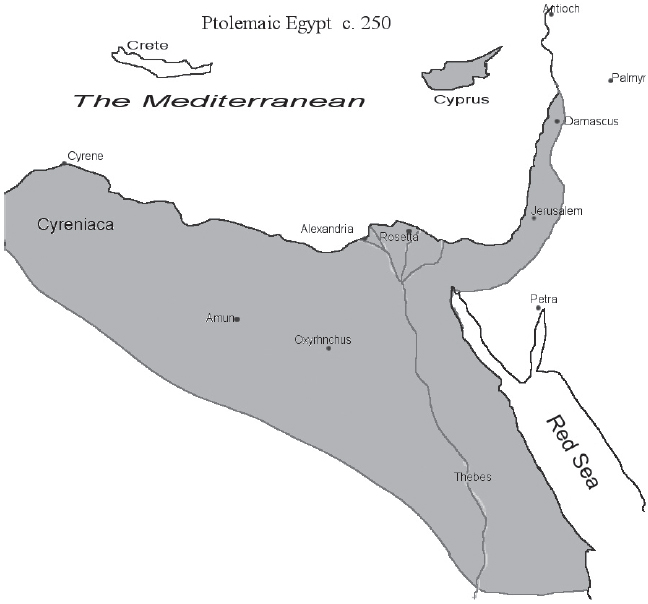

Map of Ptolemaic Egypt including disputed territories.

Anatolia and the Levant.

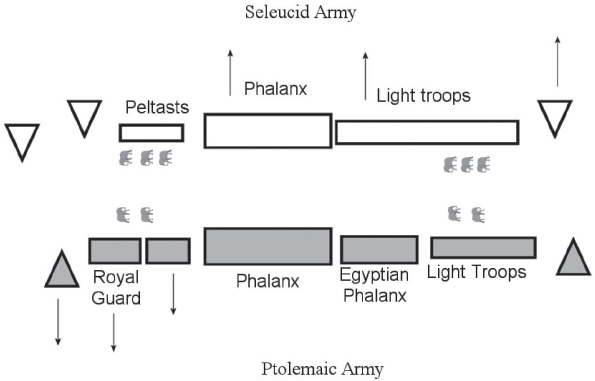

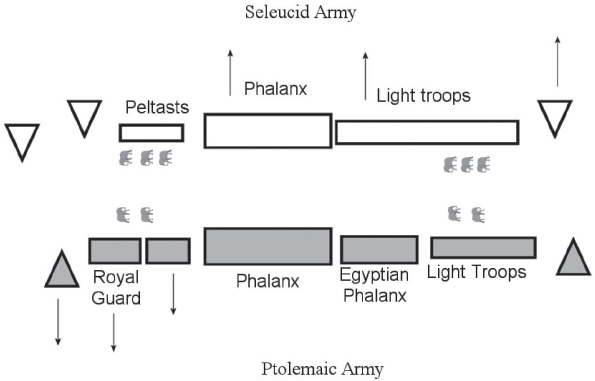

The Battle of Raphia 217 BC showing lines of retreat.

Introduction: Three Rivals Unalike

C ivilization and sophistication were no match for brute force. No matter that the Persians felt themselves culturally superior to the Macedonian army of Alexander. No matter that their cities were larger, their lands more extensive and their science more advanced in fields such as astronomy. What mattered was fighting ability, heavy armour and the Macedonian pike phalanx. Against these, Persian sophistication had no answer. The heirs of Sumeria and Babylon were slaughtered on the plains of Gaugamela and Issus, and their capital of Persepolis was first pillaged and then burned to the ground.

Alexander of Macedon took over the Persian empire, and in the process became the conqueror of the largest empire the world had ever known. His rule extended from the town of Elephantine on the Nile to Kandahar in Afghanistan, south to the Ganges river in India and west to the shores of the Adriatic Sea. Small wonder that it is said that, when he realized the extent of his domains, Alexander sat and wept, because he had no worlds left to conquer.

Yet it is one thing to be a conqueror and quite another to be a ruler. Even before Alexander fell ill and died in Babylon in 323 BC , his empire was starting to unravel. It was simply too big. A messenger travelling from Athens, if he made good speed and covered 40 kilometres a day every day, might hope to reach Alexander in India within four months of departure. A reply sent post-haste would arrive at the earliest in Athens eight months after the original message was sent, and if that message informed Alexander that he and his army were urgently needed, the reply would read, Hold on, Ill be with you next year.

Corrupt governors, rebellious tribesmen natural disasters all of these issues happened far from the seat of government, and the ruler would only hear of them long after the issue had, one way or another, been resolved. Added to which, Alexander was no Solomon. If he had talent as a ruler, he kept it to himself. His one major initiative integrating Persian and Macedonian culture was adopted wholesale from his fathers plans and failed in the implementation. Apart from that, Alexander never showed that he had what it would take to hold his massive empire together.

It may be that the Persians were right. Relatively speaking Alexander was a barbarian, albeit one with a very good army. Certainly, what happened to his empire after Alexander died did little to impress anyone with Macedonian sophistication. Alexander had not named a successor, mainly because in the fine tradition of Macedonian royalty, that heir would promptly have started scheming to assassinate Alexander before he changed his mind.

With no undisputed heir, Alexanders generals set about dividing up the empire almost before his corpse had cooled. It was agreed that (nominally) the new rulers were Alexanders children, with Alexanders half-brother as acting king. However, the half-brother was simple-minded and the children were still infants. Therefore it fell to Alexanders senior general a man called Perdiccas to actually take charge. Unlike Alexander the conqueror, Perdiccas had to be a ruler, and he quickly discovered that his new empire was basically ungovernable even for a superb politician, which he was not.