World War II Dogfights: The History and Legacy of Aerial Combat during the Second World War

By Charles River Editors

A picture of a Royal Air Force plane attacking a Luftwaffe plane during World War II

About Charles River Editors

Charles River Editors is a boutique digital publishing company, specializing in bringing history back to life with educational and engaging books on a wide range of topics. Keep up to date with our new and free offerings with this 5 second sign up on our weekly mailing list , and visit Our Kindle Author Page to see other recently published Kindle titles.

We make these books for you and always want to know our readers opinions, so we encourage you to leave reviews and look forward to publishing new and exciting titles each week.

Introduction

A German heavy bomber during the war

World War II Dogfights

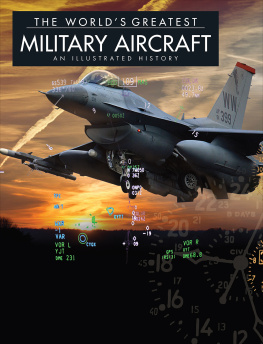

Like lethal insects undergoing a series of metamorphoses into ever more mature and dangerous forms, military aircraft moved rapidly from stage to stage of their development as the 20 th century progressed. The catalyst of war provided the swiftest impetus to this evolution. The new mechanized armies existing from the later period of World War I onward seized on the fresh technology and sought to squeeze every possible drop of advantage from it that the limits of science and the eras materials would allow.

While airplanes had never before appeared above the field of war, other aerial vehicles had already been in use for decades, and balloons had carried soldiers above the landscape for centuries to provide a high observation point superior to most geological features. The French used a balloon for this purpose at the Battle of Fleurus in 1794, and by the American Civil War, military hydrogen balloons saw frequent use, filled from wagons generating hydrogen from iron filings and sulfuric acid. The balloonist Thaddeus Lowe persuaded President Abraham Lincoln to use the airships for observation, communicating troop movements to the ground with a telegraph wire. Lowe himself reported, A hawk hovering above a chicken yard could not have caused more commotion than did my balloons when they appeared before Yorktown. (Holmes, 2013, 251). The Confederates agreed with this assessment: At Yorktown, when almost daily ascensions were made, our camp, batteries, field works and all defenses were plain to the vision of the occupants of the balloons. [] The balloon ascensions excited us more than all the outpost attacks. (Holmes, 2013, 251).

Indeed, with advances in dirigible technology, many military thinkers and even aeronautical enthusiasts believed that blimps would remain the chief military aerial asset more or less forever. These men thought airplanes would play a secondary role at best, and might even prove a uselessly expensive gimmick soon to fade back into obscurity, leaving the majestic bulk of the dirigible as sole master of the skies.

At first, airplane improvements occurred in an ad hoc, almost accidental manner during the war. However, when pilots mounting of armaments on airplanes proved a successful means of defeating other aircraft and even attacking men on the ground, a much more active and systematic development of warplanes began across the continent. Each advance prompted a countermeasure, as the two sides strove for primacy in a deadly, unforgiving environment which rewarded real advances in equipment and tactics with survival and punished poor ideas with death.

Before long, relatively powerful, heavily armed aircraft buzzed through the skies over battle-stained Europe, tearing each other apart with furious gusts of machine gun fire and sending many of the vaunted dirigibles plunging, burning, to the ground. The new era of fighting aircraft arrived in dramatic fashion, raising successful pilots to celebrity or heroic status, and laying the groundwork for the tremendous potential of airpower to achieve its next logical expansion in World War II and beyond.

By the time World War II arrived, the fighter airplane appeared as a much different beast than the purpose-built aircraft-hunting machines of 1917 and 1918. Though propellers still provided motive force, greatly increased engine power allowed these aircraft to slice through the sky at speeds of 200 mph, 300 mph, or even in excess of 400 mph when flying flat-out. Service ceilings jumped to 25,000 feet, 30,000 feet, or higher, altitudes unthinkable to World War Is aviators. Engineering and research and development began working scientifically to shave time off the climb rate and address a host of other problems and possibilities.

At the start of the war, as the German Luftwaffe first flew against Poland and then the Royal Air Force, aircraft were already swift, metal-skinned hunter-killers in the sky, with enclosed cockpits, armor, and powerful loadouts of machine guns, 20mm cannons, and, soon, rockets. But an even bigger transformation awaited the birth of the jet age, a future glimpsed briefly in the spectacular but doomed appearance of the Messerschmitt Me 262 near the wars end.

World War II Dogfights: The History and Legacy of Aerial Combat during the Second World War looks at how technology and tactics evolved during the war. Along with pictures of important people, places, and events, you will learn about World War II dogfights like never before.

The Luftwaffe and Poland

Among other provisions of the Treaty of Versailles following Germany's defeat in World War I, the Western Allies forbade their Teutonic opponents from rebuilding their air force. Determined to regain equality with the other European nations, the Germans soon flouted this restriction imposed by the hated treaty, first in secret and, in time, overtly. The Nazis naturally accelerated the process, but the Weimar Republic itself was also secretly repudiating the unrealistically excessive demands of the treaty and actually began the process in the 1920s.

In fact, the Weimar Republic recognized the pivotal role played by aircraft in modern warfare and pursued their clandestine program vigorously. The civilian airline Lufthansa developed militarily suitable aircraft at the Reichstag's behest, cloaking this research and manufacture under the guise of general cargo or transport aircraft, and the Germans also took active steps to provide training for their new military aviation program: Agreements between Germany and the USSR at the Treaty of Rapallo in 1922 led to the establishment of clandestine air training facilities at Lipetsk, Russia, by 1925 and throughout Germany the formation of innocuous gliding clubs enabled thousands of young men to gain experience in basic aircraft handling. (McNab, 2012, 8).

All the while, this represented a direct violation of the Treaty of Versailles. Though that document permitted Germany a small ground army capped at 100,000 men, the Allies prohibited the Germans from possessing even a single military aircraft. However, other circumstances distracted France and Britain during these early steps towards the Luftwaffe, and in any case, the war-weary Allies mustered little enthusiasm for enforcing certain self-evidently problematic clauses of their own treaty.

Though the Germans wanted to recreate a vigorous air force to replace the more than 4,000 aircraft confiscated by the victors at the end of World War I, the harsh economic facts of Germany's position hampered these efforts far more than any treaty. Hitler's Third Reich inherited these structural economic problems and suffered defeat largely due to its inability to find a viable strategic solution to them.