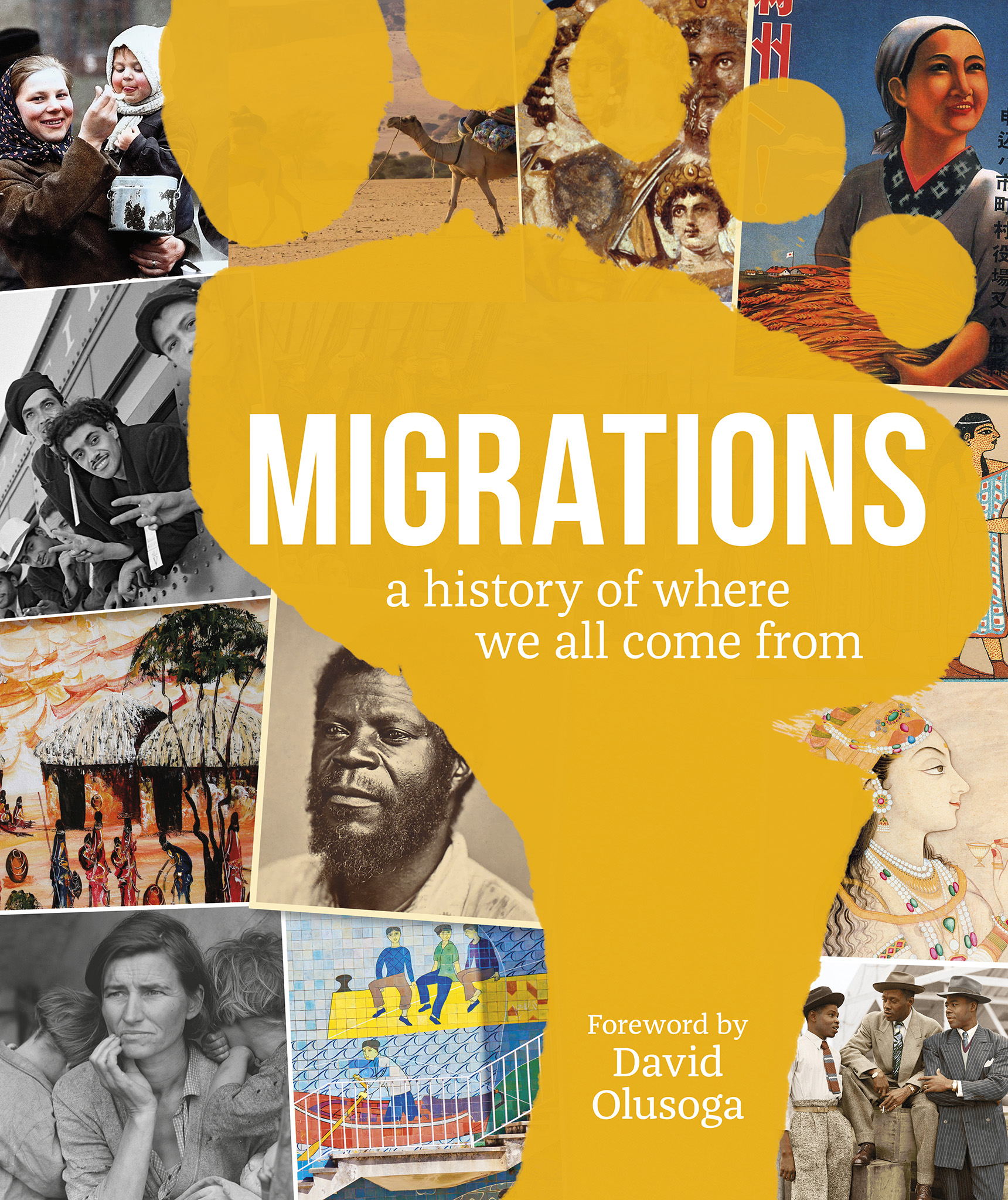

Foreword

Migration is one of the biggest stories in all of human history and a phenomenon that is set to shape the world in the 21st-century. It began over 100,000 years ago when our human ancestors first emerged in Africa, and it was through migration that humans came to occupy most of the world with migrant communities making epic journeys across land, and dangerous voyages over the great oceans in simple wooden ships and boats.

As migration has always been part of the human story, we live in a world that has been shaped by it in multiple ways. Languages, cultures, and religions have been transmitted across the world by migration, brought by both refugees and colonizers who built empires. Many of the foods we now grow and eat became part of our diets after they were introduced by migrants. Across the world millions of people have ancestors who, at one time or another, were migrants, while millions live in nations like the United States and Australia that were founded by migrants, who outnumbered the Indigenous people and stripped them of their land. Migration is so old and so vast a story that it is a background reality to our world.

There are aspects of history that are not always recognized as stories of migration and yet the resettlement of people was fundamental to them. The Industrial Revolution that began in England in the 18th century marked the beginning of one of the most important forms of migration: the movement of people from the countryside to the cities. By the middle of the 1900s, Britain had become the first country in which more people lived in the cities than the countryside. In recent decades, almost 500 million people in China have made that same journey from rural villages to urban centres. Today, the majority of the worlds population live in cities.

As this book reveals, not all global migrations were voluntary. The Atlantic Slave Trade, and the trades in enslaved Africans across the Sahara Desert and the Indian Ocean, were among the greatest crimes against humanity ever committed. They can also be seen as part of a wider trend of forced migration. After slavery was brought to an end, the British Empire encouraged thousands of people from India to travel huge distances to do the work once carried out by enslaved Africans, and later to build new railways lines. Chinese people also became migrant workers in the empires built by the European nations. Many migrations have led to the displacement and then involuntary migration of Indigenous peoples. For example, the European colonists who created new settlements in North America forced the Indigenous peoples to migrate, sometimes to reservations, their original homelands given over to new settlers.

Today, many nations rely upon migrants as workers and without them their economies could not properly operate. Many of those migrants retain strong ties to their countries of origin and millions of them regularly send money back to members of their family who still live in the countries from which they migrated. These payments are called remittances. For some of the worlds poorer countries remittances represent a large proportion of their national income.

In the 21st century, migrants leave their countries of origin for many of the same reasons that people have always left to find work and build better lives for themselves and their families, or to escape from wars and conflicts. However, a new form of climate migration has started to change migration patterns. As the climate of the world starts to change, with sea levels rising and farmland in parts of the world becoming too dry to support crops and animals, millions of people are at risk of losing their homes and their livelihoods. Migration and climate change are becoming ever more interconnected and climate migration may well shape the future of our world.

DAVID OLUSOGA

Vietnamese refugees board the USS Montague from a French landing ship at Haiphong in 1954, at the beginning of the Vietnam War.

g

1

The First Migrations

PREHISTORY

The First Migrations | CONTENTS

g

The First Migrations

PREHISTORY

Almost as soon as human ancestors evolved in the forest fringes of East Africas grasslands, they began to migrate. One group, Homo erectus , left Africa around 2 million years ago, reaching as far as East Asia. Modern humans, Homo sapiens , left the continent in two waves. The first movement, around 100,000 years ago, was unsuccessful, but in the second, from 60,000 years ago, Homo sapiens walked into West Asia and beyond. Generation by generation they pushed further, reaching Australia around 55,000 years ago and East Asia shortly after, entering Europe by 48,000 years ago, and then, finally, crossing a land bridge from Siberia into the Americas over 20,000 years ago. These earliest migrants moved in search of better hunting grounds and prospects, sometimes driven by climate change or the hostility of other groups. They were nomadic peoples, who lived in tents or other structures that could be dismantled as they went, and travelled on foot or using simple boats.

Around 9000 bce , more permanent settlements developed in the Middle East, as humans began to plant grain crops such as emmer (an early form of wheat), and reared animals like goats, cattle, and sheep. These peoples established farming villages in this Middle Eastern Fertile Crescent, while agriculture developed later, separately, in China and the Americas. With the expansion of fixed settlements, tensions arose between neighbouring groups of farmers, who now had resources to defend.

As cities and empires rose and prospered in Egypt, Mesopotamia, India, and China from 3000 bce, clashes also erupted amid increasingly complex societies made up of craftspeople, rulers, and warriors and nomadic groups, who roamed around and attacked permanent settlements. Such conflicts led to the first refugees fleeing warfare, while larger groups of people were forced often by violent means to migrate when others moved into their territory. Now armed with the first metal weapons of bronze, and travelling with the aid of domesticated animals such as the donkey, the horse, or in the Americas, the llama, and by seaworthy boats, migrants could travel faster and further, covering in months distances their ancestors had taken generations to achieve.