Legend Books

Warsaw 2022

2022 Legend Books Sp. z o.o.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or utilised in any form or by any means (whether electronic or mechanical), including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

ISBN

978-83-67583-02-2 (Softcover)

978-83-67583-04-6 (Hardback)

978-83-67583-03-9 (Ebook)

Translated and annotaded by Constantin von Hoffmeister

Translators Preface

By Constantin von Hoffmeister

This is the first English translation of Oswald Spenglers posthumously published writings on the history of the ancient world. He poetically describes the intimate nature of the bloody battles and seismic migratory wanderings that shaped the world before the advent of the Abrahamic order. The resultant boiling down of the primeval chaos and splendour of tribes and empires into a soup of mundane monotheism and nascent nations, not always representing a single and united seed, diluted the savage essence of the anarchic flow and clash between primal peoples moving amongst and against each other. The radical interpretation of historical events and processes that Spengler employs leads him to criticise the findings of his days leading historians, presenting new hypotheses that topple established doctrine and challenge the very core of what it means to be a historian. By becoming a participant and seer instead of a mere observer, Spengler is almost a time traveller, gathering data and interpreting them on the spot in his deeply erudite and epiphanically expansive mind. Instead of merely chronicling the mainstreams established events, Spengler immerses himself in the actual unfolding of the twists and turning points in the world-historical narrative that the coming of the great races, with their propensity for violence and the unleashing of their creative faculties, engendered.

As a medium, Spengler channels the spectres of the past, turning them corporeal before our inner eye, so we can smell the rust of the armor and the gore caked on the combatants blades. He describes culture clashes in the distant past, with Sea Peoples from Southern Europe raiding Egypt and mountain people from West Asia conquering Sumer. Beyond the horizon of dunes and fortresses, it was war and not peace that dictated the terms of existence, expansion and survival. Alternations of dynastic successions and regicides ensured the continuance of the empires glory under blazing suns or nestled in the shade of hills. According to perennial tradition, people fight and people die, and new people fight and new people die nothing new under the evening moon; yet hardly having uttered these words, the realization dawns on one that Spengler wrote about the procession of rise and fall with gusto to illustrate humanitys endless repetition of tasting the apple banished from the garden and forced to suffer everlasting struggle and toil on fields of honour and decay, in different climes and shifting landscapes.

Early Days of World History is a book that teaches us to remain calm when we crave impatience in the face of todays political and bellicose calamities. None of it is revelatory and nothing shall ever change. The line drawn in the sand millennia ago is still valid: stop and be devoured by the beast of time, or proceed and be slaughtered, replaced and then dutifully recorded in the annals of history. The ink collecting the dust of ages, we turn the pages to witness utter defeat followed by glorious victory and one brilliant invention nullified by another civilizational regression. The end is always nigh, they say, but in reality the end is always in the distance over those yonder craggy cliffs. We can pursue the end relentlessly. Alas, it keeps marching away from us, camouflaged among the army that is always three swift steps ahead.

Moscow, Russia

March 11, 2022

Introduction by Amory Stern: The Call of the Steppe

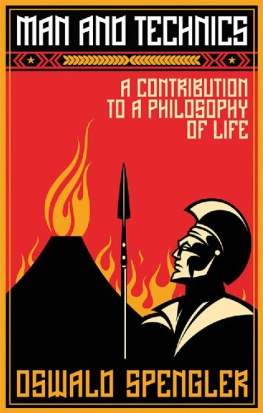

Of the many misconceptions that exist about the works of Oswald Spengler (18801936), perhaps none is more prevalent, especially among English readers, than that which regards his worldview as having remained the same throughout his writing career. He is best known for the two-volume book The Decline of the West, the first volume of which was published in 1918, the second in 1922. By the 1930s, starting with 1931s Man and Technics, Spengler had reconsidered key aspects of his philosophy. This is not very well understood by most readers, partly because of Spenglers own dubious attempts to insist his thinking had never changed.

Spenglers otherwise mostly sympathetic intellectual biographer, John Farrenkopf, expresses annoyance at what he identifies as Spenglers unconvincing insistence that his philosophy had not changed. In the process, Farrenkopf reveals the nature of what he calls the metamorphosis of Spenglers philosophy of world history. Indicative of Spenglers later philosophy is his vastly altered attitude toward anthropology and prehistory.

In The Decline of the West, Spengler had dismissed human prehistory as the primeval spiritual condition of an eternal-childlike humanity, which qualifies as history only in the biological sense. By the 1930s, though, Spengler had developed a keen interest in anthropology. This fascination led Spengler to his mature philosophy of history, in which many of his earlier assertions are effectively reevaluated.

The Decline of the West, it should be remembered, appeared in two volumes that were four years apart in publication. The first volume was written and published during the First World War, although parts of it were conceived earlier than that. Spengler had written it under the assumption that his country would win the war, and compared to his later work, 1918s first volume does not much live up to Spenglers pessimistic reputation.

The first volume does portray civilizations, including the contemporary West, as thoroughly finite. However, its focus is mostly either on drawing a sharp distinction between the medieval-to-modern West and the cultures of antiquity, or else on defending the traditional German Idealist approach to the sciences from its English materialist nemesis. Its cultural pessimism is usually more implied than overt.

By the time the second volume was published in 1922, much had changed since the publication of the first volume prior to the German armistice of 1918. In addition to Germanys defeat in the war and humiliation by its outcome, as well as the violent internal political turmoil of the early Weimar period, the Bolshevik Revolution in Russia and the nascent Mussolini regime of Italy had clearly impacted Spenglers thinking. Farrenkopf reveals that Spenglers political thought during WWI, which is not much of a focal point in most of the first volume of The Decline of the West, was rather bourgeois-based and quasi-democratic compared to the political philosophy he had developed by the time the second volume was published. In the second volume, Spengler has adopted the political views he is known for, characterized by a hostility to democracy and the belief that the Prussian archetype had made Germany great.

Despite the differences between the first and the second volume, The Decline of the West qualifies as a single project with a focused thesis. The book presents models of high cultures which, according to Spengler, go through similar historical cycles. In Spenglers terminology, the word Culture (Kultur) describes a civilizations creative epoch, in which the high culture in question is comparable to a living organism. During its Culture epoch, a particular civilization establishes its style of science, theology, politics, and art. Civilization (Zivilisation) by contrast denotes the later epoch of a high culture, in which it is comparable to an aging or dying organism. This kind of epoch is marked by the increasing predominance of big cities, all-consuming economic considerations, and a critical culture in place of a creative one.